Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

New Haven, October 1952

When I was a boy I used to wake up thinking today could be the day when everything changes. When something miraculous happens. What it would be I couldn’t articulate but I knew it would catapult me from the life I had into the one I was destined for. Everything I wanted would be mine for the asking. Power, fame, riches and glory would fall glittering from the sky like a meteor shower. After thirty-five years of waiting, some part of me still hasn’t given up.

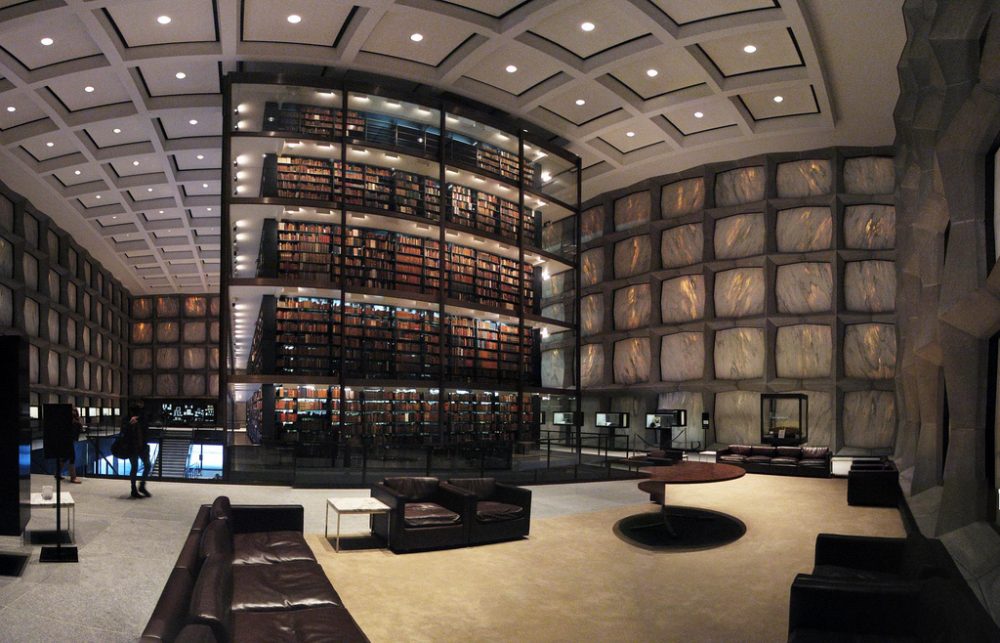

But a day that began with a two-hour commute from New York to New Haven in a rocking overheated carriage that smelt of damp overcoats and inadequately deodorised armpits wasn’t one that augured well for miracles. And now, second in line at the desk fronting Yale University’s Rare Books and Documents Reading Room, I’d begun to think the only miracle coming my way might actually be getting inside the Reading Room. My field of vision was filled by the bearlike back of the patron in front of me. Whoever he was addressing, presumably the librarian, was totally obscured by his line-backer shoulders canted at an angle that suggested a head-on tackle.

“I’m asking you to look again. Is that so hard?” The voice matched the posture, belligerent, boorish.

“I’m sorry sir. I’ve checked and re-checked but I can’t find any record of your request. If you’d just like to step over there …” A pale long-fingered hand emerged from behind his right shoulder and pointed to a desk against the wall, “and fill in another request form, I’ll be happy to …”

“Fuck that,” came the reply and the shoulders straightened. “I’ve got better things to do. I’ve got a dissertation to write lady. If you even know what that is.” With the snort of an aroused bovine, he thrust into reverse, rammed into me and planted the Cuban heel of his right size twelve solidly on my toe.

First Page Critique

In all works of fiction—and probably nonfiction, too—there are essentially two plots, Plot A and Plot B. With Plot A, a character’s status-quo condition of discontent (H. is lonesome) is challenged when opportunity presents itself (H. meets S.). With Plot B, a character’s status-quo condition of contentment (H. loves his quiet evenings of classical music) meets with an obstacle or irritant (rap DJ moves next door).

With most novels and even most stories, Plots A and B do a sort of “opportunity/irritant” tango with each other, with opportunity leading to irritant (the lover met at the coffee shop turns out to be a serial killer), and irritant leading to opportunity, and so on.

On this first page we are treated to a sly blend of Plots A and B, with the nameless first-person protagonist reaching all the way back to 1952 to tell us of a day in his life that started out less-than-auspiciously, first with a damp, “inadequately deodorized” train ride from New York to New Haven, and then with a fellow library patron stepping on his toe. Neither of those events would seem to suggest “opportunity presenting itself,” or Plot A; if anything they plant us firmly in Plot B territory.

But wait: what about that first paragraph—those devoutly-to-be-wished-for miracles falling “glittering like a meteor shower” from the sky? Thanks to that opening paragraph, by frontloading our expectations with miracles, or anyway the hope for them, the narrator performs a kind of alchemy whereby smelly armpits and stubbed toes become the stuff of dreams. We know—anyway we’re given good reason to believe—that somehow or other this will turn out to be a “miraculous” day in the narrator’s life. And so before our very eyes Plots A and B are joined in matrimony. Which isn’t to say that they are going to live happily ever after. However strong it may be, our belief in miracles doesn’t extend to them lasting forever. Still, we sense that this rude snorting bear who has injured our narrator’s toe will be important to him and to his story, that he’ll play—if not the lead—a key role in this miracle in the making.

As inciting incidents go, a stubbed toe may seem a paltry event from which to launch a novel. Yet the history of literature is rife with trivial events having epic consequences. Appointment in Samara, John O’Hara’s most famous novel, owes much if not all of its plot to a single fateful act: the moment when Julian English, the protagonist and owner of a used Cadillac dealership, throws a highball in the face of one Harry Reilly, a major investor in his business.

Similarly, were it not for an errant snowball, there would be no Deptford Trilogy, Roberston Davies’ novel sequence set in a fictional Ontario village. Instead of it striking its intended pubescent target, the snowball hits a pregnant woman, sending her into premature labor and precipitating a series of mostly tragic events. That incident opens Fifth Business, the first novel of the trilogy. As with the opening page in question, it too plants us firmly in a particular year:

My lifelong involvement with Mrs. Dempster began at 8 o’clock p.m. on the 27th of December, 1908, at which time I was ten years and seven months old.

The whole plot of Paula Fox’s 1970 novel Desperate Characters, the story of an upper middle class couple living in a Brooklyn brownstone in the 1960s, is set in motion when Sophie Brentwood is bitten by a cat—an innocuous event, it would seem, but one from which Fox extracts a grippingly persuasive portrait of a white, privileged, middle-aged couple whose hermetically sealed existence succumbs to the pressures of change.

More typically, stories whose openings catapult us into the past are apt to land us at the brink of a momentous event. From Endless Love, by Scott Spencer:

When I was seventeen and in full obedience to my heart’s most urgent commands, I stepped far from the pathway of normal life and in a moment’s time ruined everything I loved—I loved so deeply, and when the love was interrupted, when the incorporeal body of love shrank back in terror and my own body was locked away, it was hard for others to believe that a life so new could suffer so irrevocably. But now, years have passed and the night of August 12, 1967, still divides my life.

Apart from being well strategized, the opening page under scrutiny is also well-written. From its yearning first paragraph through those odoriferous commuter armpits through its rendering of the bear-like, boorish, toe-stomping library patron, it invests us vividly in its narrator’s world. That the Rare Books bear metamorphoses into a linebacker and subsequently into a bovine we might take issue with, but we would be nitpicking. This is a strong opening and I for one would keep reading.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

Peter Selgin is the author of Drowning Lessons, winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction (Univ. of Georgia Press, 2008). He has published a novel, Life Goes To the Movies (Dzanc, 2009), three books on the craft of fiction writing (Writer’s Digest, Serving House Books, Broadview Press), and a children’s picture book, S.S. Gigantic Across the Atlantic (Simon & Schuster). His first essay collection, Confessions of a Left-Handed Man (University of Iowa, 2012), was a finalist for the William Saroyan International Prize. A novel-in-manuscript, “The Water Master,” won the Faulkner-Wisdom Prize for Best Novel. His memoir, The Inventors (Hawthorne Books), which won the Housatonic Book Award, was among Library Journal’s Best Nonfiction Books of 2016. He is Associate Professor of English at Georgia College & State University. Find out more at his website.

Jane, my question of the newsletter version of this post was moot when I arrived at the website because the erring sentence had been altered, removing the two references to “her” when the protagonist was clearly stated to be a boy in the first sentence.

Was this a test to see who reads to the end of your newsletter before going to the website, or the common error that plagues us all of posting the wrong version?

Good catch!

As a reader I want the opening paragraph to be a little off. I want everything perfect except for one one tiny thing. That tiny little thing will catch my eye every time because I know the writer is up to something and I’ll be damned if he’s going to get away with it. That is my goal every time I write an opening scene. It’s fun and challenging but most of all I owe it to the reader.

This sounds like a setup for a stand-up comedy act: “There are two types of bosses…”; “There are two types of relationships…”; “There are two types of (fill in the blank)”. It’s pretty much inarguable that the first page (or first paragraph or first sentence) has strategic value but I remain skeptical of reducing a plot line to an either/or proposition. Oh, wait. That’s unless the two basic plot lines (as illustrated) somehow are commingled in a sort of quasi-legitimate union of unblessed matrimony – which act gives birth to a third, somewhat bastardized version number three! Oh, well. No matter. This will most likely navigate a circuitous path to the substance of someone’s MFA dissertation.

I’m afraid you’ve got me here, advancing a simple theory of plot only to illustrate it with an example that complicates it. In my defense I’ll say that though the example complicates it, I think the premise is sound: motivation informs plot, with characters either wanting something or wanting to get rid of or change something. With this opening, it’s not clear what the point-of-view character wants (or doesn’t), i.e., what’s driving the plot, but clearly he is hoping for something, which gives the opening tension and raises our expectations. The fact that there’s ambiguity as to which of the two plot motives will prevail adds a layer of suspense. Thin stuff for a master’s thesis. But useful, I think, in looking at this opening.

[…] https://janefriedman.com/works-fiction-can-boiled-two-types-plots/ “In all works of fiction—and probably nonfiction, too—there are essentially two plots, Plot A and Plot B. With Plot A, a character’s status-quo condition of discontent (H. is lonesome) is challenged when opportunity presents itself (H. meets S.). With Plot B, a character’s status-quo condition of contentment (H. loves his quiet evenings of classical music) meets with an obstacle or irritant (rap DJ moves next door).” Sometimes, it’s hard to believe they boil down to two plots. I guess the layers help make everything unique. […]