The Taste of Ginger author Mansi Shah discusses the challenges she faced in her quest for publication, the evolution of her focus in the process of writing about the immigrant experience, the lasting impact of books and movies, selling books to Hollywood, and more.

Mansi Shah (@mansiwrites) is a writer who lives in Los Angeles. She was born in Toronto, Canada, was raised in the midwestern United States, and studied at universities in America, Australia, and England. When she’s not writing, she’s traveling and exploring different cultures near and far, experimenting on a new culinary creation, or working on her tennis game. For more information, visit her website or follow her on Instagram at @mansishahwrites.

KRISTEN TSETSI: What books did you most like to read as a child, and what attracted you to them?

MANSI SHAH: I was a voracious reader as a kid, and so I read anything I could get my hands on from our local library! The ones I most remember reading were Judy Blume books, the Nancy Drew mysteries, Sweet Valley Twins, and Sweet Valley High. I also recall reading books about WWII, like Number the Stars by Lois Lowry, and I am still drawn like a magnet to books about the Holocaust, but there were not too many middle-grade books that dealt with that subject. Even from my earliest memories, the books that stuck with me most were those that explored injustice, perseverance, and humanity.

I think what attracted me to books in general was that I could transport myself to other places and times through those pages. My childhood had financial ups and downs, and we moved several times, but I could escape into stories and take a mental break from whatever was going on at the time.

You wrote your first book at nine years old, turning in a chapter a week to your teacher (after getting permission) rather than the assigned short story once a week. Do you remember what you wrote your book about, or what you think you probably would have written about?

I do! Maybe better than I should! It was called Valley of the Dolls and was a mystery about two kids who got lost while hiking and stumbled upon an eerie abandoned small town. In one of the houses, they found dollhouses that represented a miniature version of the town. In one of them, they saw the dolls positioned to show a murder, and the two kids then went about trying to find out what happened in the town and why it was now abandoned.

My Grade 4 teacher, Mrs. Strube, had my handwritten book bound together at the end of the school year, and I wish I still had it with me so I could remind myself how the mystery was solved, because I’ve forgotten the ending! One day, I’m going to have to go digging through the boxes my parents have stored in their garage to see if I can find that original book.

You knew you wanted to “write a real book, some day,” but you went on with life and school, studying psychology in college and then veering into law. Did you do much creative writing between your fourth-grade book and The Taste of Ginger? If not, did you have other outlets throughout your years of professional work and studying to satisfy creative urges?

I dabbled in creative writing through my schooling years, doing some poetry and short stories, but not really doing much else. During my early lawyer years, I had started a couple novels but never got more than a few chapters into them before life and work took over.

In hindsight, I think the projects I’d started were never completed because I was writing what I thought I should write (legal mystery/thrillers) rather than what I was passionately interested in writing, which was The Taste of Ginger. I did, however, always maintain a creative outlet to balance my left and right brain, and I think the need for that balance comes from my mom. I grew up watching her engage in many creative endeavors, from cooking to ceramics to floral arranging to other artwork, so part of me was always inclined toward that.

My university years were spent diving into cooking and baking, and learning how to express myself through food (something I’m still obsessed with today!), because when I moved out of my parents’ home, I knew the only way I’d get to eat the Gujarati food I grew up with was to learn to make it myself. I also tried different painting classes, until I found the one that resonated most with me. Surprisingly, it was Chinese brush painting! For many years I painted in that medium and would probably still be doing it today if my teacher hadn’t retired many years ago!

I also found small projects along the way like scrapbooking, interior design for my home, photography, cross-stitch, and various other arts and crafts to keep myself engaged in artistic expression.

You said in a Good Life Project interview that years into your legal career you began to feel like writing was a better vehicle for impacting change and reaching people, that you could say more things “with fewer rules.” The driving force behind The Taste of Ginger, you said, was your mission to offer something to young people from immigrant families looking for books that represented them and their experience.

How easy or how difficult was it for you to balance the tasks of illustrating the challenge of half-belonging in two very different worlds and ensuring that the story, the characters, didn’t get lost in or diluted by the message?

This is such an interesting question! I think it was relatively easy for me to write immigrant characters who went through life while questioning their identity and belonging because that is my lived reality. My experiences and choices were not the same as my protagonist Preeti’s, but I believe the underlying question of belonging resonates for most people, regardless of background.

For me, the highest priority was to craft a relatable and engaging story that kept readers turning the pages. Part of that meant that the story and characters are intertwined with the underlying themes of acceptance, identity, and trying to find out what home really means to them, and I do think it means something different for each character in the book. My goal in writing The Taste of Ginger was to keep the story and characters at the forefront while giving insight into the introspective journey that so many immigrants experience, whether they go through Preeti’s specific challenges or not.

I have kept so much of my assimilation and acculturation journey to myself, and many people in my life would not have appreciated the many layers of thoughts I had as an outsider in even the simplest of situations, and I wanted to illuminate that process. The narrative around how my main character Preeti responds when someone cuts in front of her in line at the grocery store is a good example, because that seemingly innocuous transaction is more fraught and thought-provoking for her based on her past encounters than it might be for someone else who never experienced what she did as a teenager. My hope is that these small vignettes throughout the book help the reader understand her decisions and conflicts on a deeper level.

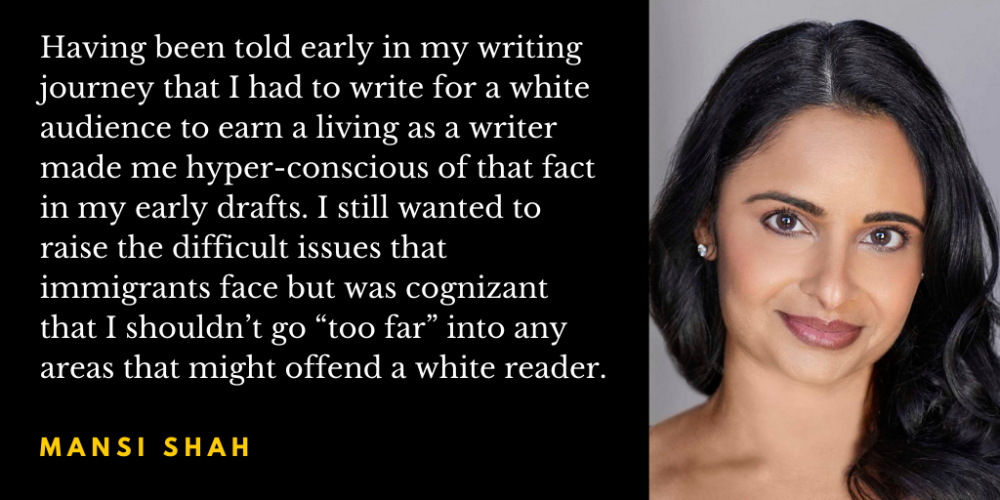

In your early days of writing The Taste of Ginger, you said in the Good Life Project interview, you thought you would need a primarily white audience for your book to sell, so you initially did a lot of “whitewashing” in the early draft, avoiding or watering down Indian elements that might trigger white readers. After you realized the story needed to contain those elements to honestly reflect the cultural experience you’re familiar with (and to resonate with the audience that drove you to write the story, in the first place), you brought them back in.

What kinds of things were you hesitant to include, at first, and what did it feel like as you were writing to discard that caution and just write the story you wanted to write?

Having been told early in my writing journey that I had to write for a white audience to earn a living as a writer made me hyper-conscious of that fact in my early drafts. I still wanted to raise the difficult issues that immigrants face but was cognizant that I shouldn’t go “too far” into any areas that might offend a white reader. For example, I didn’t address the notion of “color-blindness” that was a common and well-intentioned view that I had often heard while growing up. I also didn’t delve as deeply into what it feels like to be a non-white immigrant in a predominantly white law firm, and I wasn’t as direct about referring to America’s racial hierarchy as a caste system. I felt like I hinted at those issues but didn’t give them the justice on the page that they deserved.

And even beyond the ideas and how they were expressed, I kept my white audience in mind and italicized and provided embedded definitions for any Gujarati words, which was the norm at the time for non-English words. It seemed like it was an uphill battle to get a book centering on an Indian immigrant experience published in the first place, and I couldn’t also ask industry decision-makers to google the words.

But with each revision, I became bolder in what I wrote because simultaneously the world was changing, and I felt like society was evolving in a way that I could be more direct with each draft. And I was changing alongside it. I started writing The Taste of Ginger at the age of 29 and was 40 when I got my book deal. Highly formative years for anyone! During those years, I became less afraid of what would happen if I wrote something that challenged the way people think about immigration and assimilation.

Even with the personal confidence I’d been building, it wasn’t until the global racial reckoning in 2020 that I felt the freedom to fully write what felt authentic and true to my main character’s experience. Over the years, I began to feel an obligation to provide authentic representation to Indian immigrants, and to show our thoughts and experiences in an honest way that is relatable to us. White readers have countless books they can turn to and catch glimpses of themselves, so it didn’t make sense for me to focus on that audience when representation for readers from my own culture was so lacking. I kept asking myself who I would have grown into if I’d had more Gujarati representation in the stories I had read—seen familiar names, foods from my dining table, cultural customs that normalized those I never saw outside of our family home—and I wanted to provide that to the generation behind me. And given society’s awakening to the experiences of people of color in Western societies, I knew that people of all backgrounds were on a quest for understanding and appreciating the differences between us in a way that I had yet to see in my lifetime.

With that goal in mind, I delved deeper into the thoughts of my Gujarati-American protagonist and really painted a view of the conflicts she faced within her family, among her friends and colleagues, and in her romantic relationships. I removed the italics from the Gujarati words and the explanations that had never felt right to me. The Taste of Ginger is a first-person narrative of a Gujarati-American woman, and she knows what those words mean, so she would not pause to explain them. It is clear from context whether she is referring to an item of clothing or food or term of endearment, and I realized that is enough. The words are not foreign to her, so in the same way that an author writing from the perspective of a white American protagonist would not be expected to explain pizza, skirts, or sweetie, I gave my main character that same deference. (And all the words in my book can be googled for anyone who wants further understanding of any of them; I confirmed that myself before publication!)

Making these changes felt like I was finally writing the story I set out to write when I was 29, and it was liberating! I had crafted a story that I was truly proud of and that was authentic to everything I sought to achieve as a writer, even though I was terrified about how it would be received. I did not even let my family read it until just before its release date! Yet, even with my liberation high, I turned in my final draft to my editor and waited with bated breath worried that she would come back and tell me I’d gone too far, that some of the ideas in the book would be too alienating, that we needed to explain the “foreign” words. Fortunately, she loved everything about the changes, and I knew I had the right editor and ally in my corner!

The Taste of Ginger took ten years to sell. Part of the difficulty you faced when trying to get an agent was that some agents you queried would say they’d “just signed an Indian author” or would have recently had “a book like this” on their list. Considering how many books by white Americans are published that are similar to each other in their broader subject matter (soldier stories, murder stories, love stories, detective stories, coming-of-age stories, etc.), how did you receive that feedback, internally, and how did you stay motivated to keep looking for an agent?

That type of rejection was one of the hardest parts of the journey for me, because it was completely out of my control. I wasn’t being told that there was a problem with my writing, or voice, or story. If I had been told any of those things, I could have worked harder, spent more time revising, or come up with another story. But that there wasn’t room on the shelves for what I had written was both demoralizing and motivating.

I had all the thoughts you mentioned, including that no one would ever say that to a white author because there’s room for multiple stories from that point of view. I’d not yet read a single book that reflected my Gujarati immigrant experience, and very few existed featuring characters from other parts of India, but the message from the publishing industry seemed to be that the 1.4 billion people of Indian descent with their varying cuisines, languages, dress, and customs were interchangeable, and the handful of books that existed were enough to satisfy that readership.

My most memorable rejection was in 2011, when an agency meant to send an internal email but instead replied to me (that dreaded act that we all fear), so I saw their true unfiltered thoughts: “Solid voice. Great title. Though I’m worried because you said the India wave has passed…”

I spent a long time thinking about my culture as a passing “wave.” What kept me motivated from that response and others like it was that none questioned my writing abilities. I knew my culture’s stories were worth telling, so it was the fuel to keep going until I found the right agent and editor who wanted to join me in my efforts to disrupt the publishing industry!

Your editor passed on the novel, at first, but said she’d consider it again after a revision. Your agent advised against doing the revise-and-resubmit. Why?

At the time when my current editor initially passed on the book, I was deep into writing my second book. And I had been revising The Taste of Ginger for nearly a decade at that point, so I felt like it was time to move on from it. My agent suggested that I should only revise and resubmit if I felt I wanted to do that for myself, but that in her experience, when publishers weren’t willing to go through the revision process with the author—especially in my case in which the revisions were not that substantial—then it was unlikely that they would pick it up later.

Basically, she nicely told me, it was a longshot. Based on the feedback I’d been getting on The Taste of Ginger, I was more confident in my ability to sell my second novel, so I thought I would be best served focusing my energy there.

After about a year and a half, the same editor contacted you to ask if the manuscript was still available, and you had some mixed feelings about her interest. Can you talk about that a little bit and about how you’re feeling now?

The timing of my offer was strange, because we had stopped shopping The Taste of Ginger over a year earlier. We were amid the 2020 global pandemic, and a racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd and too many others and rampant acts of Asian hate. Voices that had often been disregarded were calling out for change more than I could remember at any other point in my life, and people seemed to be listening.

The Taste of Ginger, a story about an authentic Indian immigrant experience and the search for identity and belonging when someone straddles two cultures without ever fully being accepted in either, is the type of story that it seemed like people were ready to hear. When my agent called me and told me I had an offer, I was stunned. When she told me who it was from, I was even more shocked, because I had not made any of the revisions that had been discussed 18 months ago—had not even moved a comma—but now that same manuscript was worth making an offer without those revisions.

I wrestled with what had happened in the world to lead to this point, and it was a complicated mix of emotions. I could not divorce the publishing industry welcoming content like my novel from the many lives that had been tragically cut short to lead to this pivotal moment in my life. My lifelong dream came true against the backdrop of all this pain, so that duality resulted in a lot of introspection. I questioned if I was getting an offer because it was the current “wave” to sign authors of color—I didn’t want to be seen as a token or quota metric. I wondered whether I’d have to change elements that a white audience might find uncomfortable or controversial. While my manuscript hadn’t changed, it felt like everything around it had.

I talked to my agent for two hours and asked her whether she thought it was the right career move for me to sell both books without having even tried to shop my second novel, yet. Both her gut and mine said that it was. It was a foot in the door, and then I’d let my writing and characters do the talking.

It was a gamble, but I’m thrilled with how things turned out! I love my editor, and she has steadfastly championed the authenticity of my stories, always encouraging me to delve deeper into the minds and hearts of my Indian characters. When I was worried that she wouldn’t like new elements because they handled controversial topics too directly, she would respond that those additions were among her favorites. I’ve gotten so much more than simply having a foot in the door, and I am forever grateful for the opportunity to bring these stories to readers.

As an entertainment attorney, you could have written a screenplay instead of a novel and had little trouble getting someone in the film industry to consider it for production (or at least read it). But telling the story was, you said, a creative journey that had to be authentically you, and books have always been authentically you—you read them in the library as a child, had them available when your family didn’t have access to movie tickets, and could “retreat into these characters, these pages.” Part of your goal was giving that same access to young people who can use it now.

You also noted in the Good Life Project interview that you think Hollywood “has shaped public perception around the world in so many ways. No matter where you go, American television and film is present.” Now that you’ve accomplished the novel (and have another on the way), would you consider writing for screen in order to expand your reach and influence?

It is so quintessentially me to make life more difficult than it needs to be! Yes, I am fortunate that I do have access to key executives and talent representatives in Hollywood and could get people to at least consider my work and give it a fair look, with no guarantees beyond that, of course!

I know Hollywood much better than I know publishing, so I could certainly envision expanding my writing for screen. The main goal I hope to accomplish with my writing is to amplify representation and tell authentic stories. In a perfect world, I’d love to do both books and screen and would be immensely grateful if life presents those opportunities to me.

In a November 1945 issue of The Atlantic, Raymond Chandler wrote of working as a writer in the film industry, “On the billboards, in the newspaper advertisements, [the writer’s] name will be smaller than that of the most insignificant bit-player who achieves what is known as billing.” This when it’s the writers who generate the stories, provide the words the actors speak, create from scratch the characters actors portray.

But the inequity isn’t just about visual recognition. Carrie Pilby author Caren Lissner writes in her 2017 Atlantic account of the adaptation of her novel into a movie for Netflix that authors who sell the screen rights to their novels “often get a sum equal to about 2.5 percent of the [production] budget,” and according to the video and television production company Beverly Boy Productions, there’s often a cap, so even if the budget increases, the writer won’t benefit from that higher budget. Writes #teambeverlyboy on their blog post, “That means, even if the [original $10 million] film budget increases, to say $100M? You’re still only going to get $225,000 for the rights, which is still a rather substantial amount of money.”

It’s hard not to be disappointed by the fact that many writers do still say, “Oh, yes, thank you,” to being one of the lower paid people on the team because not only are they being graced with the attention of a production company, which means exposure, but film rights probably do earn a writer more money than they would normally otherwise make. That doesn’t mean the payment, when compared with the rest of the budget allowances and/or the adaptation’s potential earnings, is anywhere near what should be considered adequate compensation for the writer’s inarguably critical contribution.

This all reads as naïve, surely—it’s just how things are in Hollywood—but based on what you’ve seen in your time working in Hollywood, is there potential for authors selling film rights to their work to unify, even in an unofficial way, and demand no-less-than compensation in their contract? For example, “Will not accept a budget cap,” or, “Budget cap, fine, but I also want 2.5 percent of the film’s/series’ earnings for the life of that film/series”? If writers were less willing to accept being treated as content creators for producers rather than as important contributors and artists in their own right, could there be a shift in the perception of their value to the industry?

This is such an important question! Like with publishing or any other established industry, shifting “business as usual” in Hollywood will be a heavy lift, but the optimist/activist in me thinks that we still need to try. As an initial matter, the odds of a book that is optioned actually being produced and distributed is exceedingly rare, so those initial option payments reflect that and are typically very modest. When the options are exercised and the project is being produced, that’s when the author gets the largest payment they are likely to get—typically a percentage of the production budget. Those amounts seem high to authors who are used to getting a very small royalty on each unit sold of their book, but it is often the case that the author gets less compensation relative to the other talent working on the adaptation.

Having had first-hand experience in both industries now, I can see the competing interests at play. Screen adaptations are expensive—generally much more than publishing a book—and decisions are driven by costs and budgets. There is a certain amount that the talent working on the adaptation will be paid from the budget, and that pot of money gets divvied between them, including the option/rights fees to the author. Given that system, it would involve talent and the studios working together to rethink how they allocate production budgets, because if the author is getting paid more, then it likely means someone else is getting paid less than what they have been accustomed to receiving. If it’s not other talent reallocating some of their compensation, then it would be sacrificing something else in the budget, like a special effect or location or wardrobe, and that is also difficult once someone has a creative vision. At the end of the day, it’s all tied to the numbers, and I think it’s going to take a lot of work to change how production budgets are allocated.

This is not to say authors shouldn’t fight for a new normal and seek to change how they are compensated for their source material, but the reality is that those fights gain more traction when done by the most prominent authors who can afford to withhold their rights and not see an adaptation made unless the standard changes. Very few writers are financially able to decline that hefty—even if comparatively less—rights payment that comes with an option being exercised. But if the prominent authors were to seek change, it is more likely that such changes would eventually trickle down and become the standard for everyone. For the time being, however, I think the best thing authors can do is attach themselves to the adaptations because there is more compensation for those who are actively working on the screen versions.

With so many streaming services forming their own production companies, there are increasingly more avenues for writers to have their work adapted. Is there something you think every writer entering into film rights negotiations for the first time should know, watch for, or ask for before signing a contract?

We are living in an era where content is everywhere and available on demand, and that has been great for expanding representation in so many areas. The best advice I have regarding a screen rights deal is to make sure to have the right talent rep in place.

All the studios have preferred agencies and/or talent firms with whom they deal, and those top representatives often have pre-negotiated deals with studios such that even if you are just starting out as an author and selling screen rights for the first time, you could benefit from the talent rep’s already established relationship with the studios. In Hollywood, my view is that those relationships matter just as much as the written source material when it comes to getting the right deal.

As versed as you are in the film entertainment industry, the publishing industry was new to you when you sold your novel to Amazon imprint Lake Union Publishing. In the decade you spent waiting to be published, you must have imagined what it would be like. How did reality match up?

Hearing the news from my agent that we had an offer on The Taste of Ginger and my second book was completely shocking! At that point we had shelved it, so I had no reason to think The Taste of Ginger would live anywhere outside of my laptop!

Having my childhood dream come true can only be described as surreal. The early reviews for the book have gone well beyond anything I ever expected. I’ve received heartfelt messages from immigrants who have felt seen and understood for the first time in a book, and from readers of all backgrounds saying that it gave them a better understanding of the immigrant experience and they will move through their lives with more empathy and compassion as a result. There is no higher praise I could ask for!

I have challenged myself to be open to the debut author process and not put demanding expectations on myself (no easy feat for this overachiever!), knowing that once the book was published, there was very little I could do to make it a success and its performance would rest on the opinions of my readers. Before the novel was published, I would have said getting 1,000 reviews was more than I could have expected, but the book blazed through that goal in a matter of weeks!

As time passes, I admittedly am moving my goalposts from what they had been pre-publication (Joanne Molinaro, The Korean Vegan, has a great post about moving goalposts that has stuck with me). It’s part of my personality to achieve one thing and then look to the next, but with this journey, I’m pausing to cherish the successes as they occur, before, of course, resetting that goalpost!

I’d say the biggest adjustment for me when it came to my publishing deal was that I wasn’t negotiating it myself. I’ve built an entire legal career in which I negotiate on behalf of others, and it was a bizarre situation to hand over the reins to someone else for the deal that I had dreamt of for so long! That said, as the adage goes, “A lawyer who represents herself has a fool for a client,” so I knew I needed to get out of my own way! I am still learning the publishing business and am beyond grateful to have my knowledgeable, experienced agent advocating on my behalf, while accommodating my higher-than-average need to know every detail of the negotiating process.

Author Paulette Kennedy asked what advice you would give up-and-coming writers. You said, in part, “There is so much happening all at once and so much of it is good, but it’s easy to get overwhelmed with everything there is to do. … Give yourself some grace if you can’t fit in everything that you wanted to do on the marketing and promotion side.”

What was the “everything there is to do” in your case, and how did you manage the overwhelming moments?

Getting the initial deal is just the first step, and I knew that if I wanted to keep getting deals the book needs to meet the expectations of readers and my publisher. By publishing with Lake Union, it is a unique model compared to traditional Big Five publishers, so my experience was different from that of the few other authors I knew. In my case, with the exception of a pre-release blog/social media tour in December, Lake Union focused on marketing rather than publicity. This meant their efforts were spent on things like getting my book selected for the First Reads Program (which is huge exposure for a debut author!), targeted ads via search engines, and using Amazon’s algorithm to make people aware of my book in the first place, given that discoverability is one of the biggest hurdles to a book being successful.

On the other side, Lake Union doesn’t assign every author a publicist (and I was not chosen to have one), so all the post-release PR opportunities were the result of my own hustle and the help of my friends. For example, I am fortunate to be friends with Jennifer Pastiloff, bestselling author of On Being Human, who has an extensive network and loyal following. She organized Good Life Project for me (and I still can’t believe it, because I’ve been a fan of Jonathan Fields for years before I had a book deal!) and put me in touch with Shelves Bookstore, a wonderful indie bookstore owned by Abby Glen, for my virtual book launch. Having been through her own book launch with a Big Five publisher, Jen was able to give me great advice and guidance on top of the great connections she helped me make. I honestly cannot imagine how I would have survived without her, because she became my de facto publicist!

My other podcast interviews, including Best of Women’s Fiction and The Jabot, were from me reaching out to those places on my own. I was given print and digital ARCs, but I was responsible for finding book bloggers willing to read and review and sending the materials out myself—there were many trips to the post office, but I am now friendly with the staff at my local branch!

My biggest hurdle and the area in which I had to give myself the most grace was social media. I’m not a natural at it and self-promotion is hard for me, so I knew I needed to focus on promoting other authors in addition to myself. I don’t think people realize how much time and effort goes into these posts or reels that we then spend a few seconds viewing.

Given that I still work full-time as an entertainment lawyer, balancing social media on top of my day-job and the actual writing was too much. I had talked to a friend in PR, who had told me I should have one post per day and 3–5 stories each day, and within days, I knew I couldn’t maintain that schedule. So, now, I do my best with the time I have, and I try not to get down on myself if I can’t stay consistent. And the reality is that I don’t have enough reach on social media to move the needle on sales in the way that Lake Union does, so that takes much of the pressure off, and I can use social media for the purpose I enjoy most—engaging with readers and authors!

Going from being a lawyer to being an author promoting her work online must be interesting. Are there platforms you’re more/less comfortable with than others?

Social media is the hardest part of the author job for me! I created social media accounts after I got a book deal because I knew it was necessary, but before that, I was the person who had gone years without engaging with it. My lawyer job is all about confidentiality and privacy, and I am an introvert who has always preferred quality one-on-one time with people than interacting on a mass scale, so I was not primed for this.

While I’m not the most regular content creator, and I’m not the person who is likely to have anything go viral, I’ve found it’s been a wonderful way to connect with readers and authors. Some of the heartfelt messages I’ve gotten from readers have been so moving and have helped motivate me to explore new themes and ideas for future works. And there are so many wonderful bookstagram and booktok accounts that are helping with discoverability of books like mine, and I’m grateful to them both as a reader and a writer. I have more books in my TBR list than I can likely consume in my lifetime, but it’s good to know that I’m spoiled for choice! And I’m grateful for the connections I’ve made with other writers through social media. I’ve genuinely made true friendships and found a community that is so generous and supportive, and I hope we will actually meet in person one day!

When it comes to platforms, I was given the advice early on to pick one and focus on that, so my platform of choice is Instagram, and you can find me @mansishahwrites. I tend to carry over my content to Facebook and Twitter as well, because they’ve made that easy for even a neophyte social media user like me to do! I’ve used Facebook, so I have a general understanding of how that works, but Twitter still mystifies me if I’m ever on the platform, and I probably need to watch a tutorial to learn some basics.

I knew I wanted my socials to authentically represent me, so they focus on the things I love most: highlighting books by underrepresented authors, exploring countries for my next novel, cooking the Indian food I grew up with, and finding the right European wine to pair with my culinary adventures…the same themes that are often present in my books!

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called a novel “for right now” and “scathing social commentary.” She’s a former adjunct English professor, former reporter/columnist/feature writer for a daily newspaper, former writing instructor, and a former editor of the literary journal American Fiction (New Rivers Press). She lives in Connecticut.

Thanks, Kristen. This is an amazing in-depth interview. And what a journey. Mansi, I have gone to get your book!

Thank you, Kristen, for this brilliant interview. Very relevant to me as a former refugee/immigrant. The issues raised in this interview do resonate with my personal experience. I am as yet to get a book published. Working on it; and with some good luck, I hope to have a book published in the near future.

Re Ms Mansi Shah: My sincere congratulations upon getting your book published. It is a great achievement. Make the most of it. I look forward to reading it in the near future. I wish you every success in your writing career.