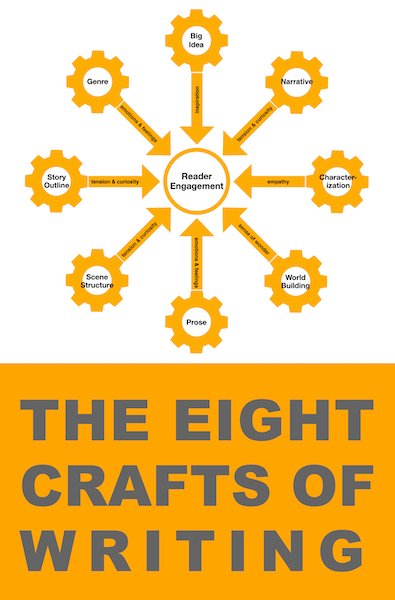

Today’s post is excerpted from The Eight Crafts of Writing by Stefan Emunds (@StefanEmunds).

“Make the audience put things together. Don’t give them four, give them two plus two.”

—Andrew Stanton

“Drama is anticipation mingled with uncertainty.”

—William Archer

Your goal is to get total strangers to read the first chapter of your book and hook them enough to read the second. And the third. And the fourth. And so forth. But what makes readers open a book and keeps them turning the pages?

In part, curiosity and tension.

Curiosity is an intellectual affair

People are curious souls. They wonder how it feels to walk in someone else’s moccasins for a moon. Or in someone else’s high heels. Is the grass really greener on the other side? How does it feel to have no garden? How does it feel to have an entire park as a garden? How does it feel to have a house in the middle of a desert? People read to experience things they can’t or don’t want to encounter in real life.

Curiosity manifests in two ways:

- Expectation or anticipation (positive curiosity)

- Worry (negative curiosity)

Writers maintain readers’ curiosity by raising questions, in particular, the global story question: Will the protagonist succeed or not?

But don’t just raise any questions. Questions need to come with challenges.

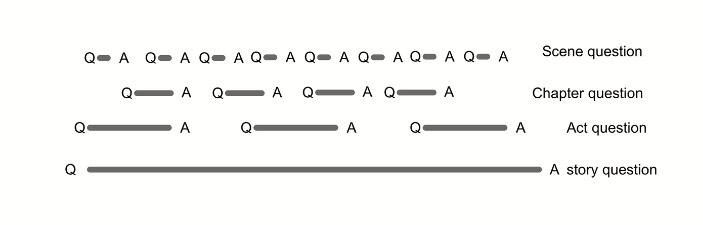

To maintain reader curiosity, you can raise and answer multiple questions on multiple levels—for example, a story question, an act question, a chapter question, and a scene question. Try to keep two to three questions open at any given time. Raise two questions in your opening and answer one. Then, raise two new questions and answer one. Then raise two new questions and answer two.

Take the world of TV and movie writing: screenplays have seven or eight sequences, and each sequence begins with a challenge/question and ends with an answer—success or failure. You can do the same thing with chapters and acts.

You can boost reader curiosity with dramatic devices, like a cliffhanger. A cliffhanger separates a question and delays the answer with a chapter, act, or even book break.

Tension arises from the discrepancy between want and reality

To feel tension, readers must sympathize and/or empathize with characters or at least want to know what happens to them. Dwight V. Swain once said, “Your reader must care what happens. Otherwise, he won’t worry, and worry is the big product that a writer sells.”

Tension manifests in two ways:

- The reader wants something to happen—e.g., the protagonist succeeds.

- The reader wants something not to happen—e.g., that the protagonist fails.

The antagonist and adversity keep the protagonist from realizing her want. The greater the power divide between the protagonist and antagonist, the greater the tension.

- Small power divide: Readers wonder whether the protagonist will succeed.

- Large power divide: Reader wonder how on earth the protagonist could possibly succeed.

- Optimal power divide and writer jackpot: Readers are convinced that it is impossible for the protagonist to succeed.

In the case of a series, writers give their protagonists an overall or umbrella want and keep them from achieving it. The Blacklist would end the moment Elizabeth Keen is safe. The 100 would end the moment these guys get a life. Tony Soprano better not succeed with his therapy, and Uhtred better not get his kingdom.

Writers can use dramatic devices to increase tension, for example, by:

- Raising stakes

- Creating expectations

- Introducing red herrings

- Dropping unexpected twists

- Introducing deadlines

- Increasing adversity/conflict

- Complicating complications

- Hinting at subtext

Tension works together with curiosity

Ever heard that stories are either story-driven or character-driven? They should be both. Conflict alone is not an engager. But conflicts keep protagonists from realizing their story goals, which engages readers and produces tension. And conflicts give rise to the question of whether and how the protagonist will prevail.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Stefan Emunds’s book, The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Stefan Emunds loves to write visionary fiction, historical fiction, magical realism, as well as enlightenment non-fiction. Most recently, he’s the author of The Eight Crafts of Writing. Prior to becoming a writer, he worked in telecommunications and as a business development manager in Europe, Middle East, and Asia. For almost three decades, Stefan has pursued a spiritual career at B.O.T.A., a modern mystery school teaching the arcana of Tarot, Qabalah, Gematria, esoteric Astrology, and Alchemy. At the moment, he lives with his son in the Philippines. Learn more at his website.