In today’s guest post, Maggie Kast (@tweenworlds), author of the novel A Free, Unsullied Land, discusses the role research plays in the development and evolution of a historical novel.

I’ve often been advised to write the story first, then do the research. The idea is not to get bogged down in facts while discovering the story’s narrative arc, its unique logic and necessity, its essential argument. Annie Dillard has written that writing is like “a miner’s pick,” an instrument of exploration and discovery, and so it is for me. I don’t know where I’m going until I get there, and many paths I try turn out to be dead ends. Research can kill the search, replacing story with history. So I turn from the Internet, that bottomless source of facts, and seek imaginative connections between what happened and why. Of what did the queen die? There will be plenty of time later to change that hot dog to lap cheong sausage, put the Eiffel Tower in the correct arrondissement or switch out a car for a horse and buggy. The advice against research has served me well.

But research need not be limited to objective facts or historical events. Subjective experience and memory are other forms of research that tether fiction to the real and help to satisfy what David Shields has called reality hunger, today’s yearning for the feel of reality, its touch and taste.

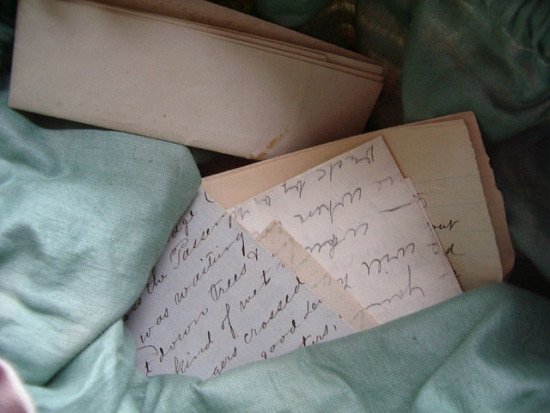

In 2003 my mother died, and her letters came to me, some written before she met my father, some when they were courting. Hidden between the lines on the yellowed, typewritten sheets, I found a person I had not known—a lively, sassy girl who had a clever way with words. Language for her was both gift and burden, and she suffered when they could not connect to the anguish at her core. Unable to speak or even feel her anger at her tough and disapproving mother or her fear of her temperamental and over-affectionate father, my mother knew one thing. She wanted out.

She got her wish, but at a price. The mother I knew, competent and generous, had sacrificed her verve for a safer life as stable wife and mother, later writer and community activist. I wanted to bring the girl of the letters to life, to give her adventures she never had and probably never wanted, to let her great potential play out in fiction. These letters were my first source for A Free, Unsullied Land, a novel about Henriette Greenberg’s coming of age in Chicago, 1930. Henriette is not my mother, but details of her experience, filtered through me, contribute to the sensory aspect of her world.

This process, theft and filter, is fraught for me with guilt. I take my parents’ material for my own and twist it into new form. I imitate my mother’s way with words; a few I steal. Though my parents are gone, some people living will surely take offense, and that I will regret. But I think Ma might like the time I’ve spent hanging on her words and inhabiting her world. I’ve made use of her wit and intelligence as well as her conflicts. To me the novel is a tribute to my parents, and I can only hope that they’d agree.

The letters revealed more about things of which I’d heard, like Ma’s delight at drinking “dark stuff” or “light stuff” in Prohibition’s speakeasies, her fear and dislike of the family dinner table, and her sense of entrapment by family pressures as she agonized over wedding invitations—whom to invite and whom to exclude. Foods that Ma made, like finger rolls stuffed with creamed chicken, and others that she talked about, like Mrs. William Vaughn Moody’s Lion and the Lamb, made their way into the novel. The jazz Ma loved, like Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke; the gutbelly blues of Bessie Smith, and the piano music of Jelly Roll Morton play in the background throughout the novel. Songs Ma sang, about a “thief and a gambling woman, drunk every night, ” or a canary with circles under his eyes, all contribute to the novel’s soundtrack.

Eventually the letters, like all research, threatened to overpower the story. I discarded many scenes they’d inspired and put the letters aside. More physical sources stepped in as touchstones to the real, and I found that some research could serve as prompt to my imagination. I went to see the house where Ma grew up and imagined her bed covered with childhood’s stuffed animals, then conflated this house with one where my grandmother later lived, with its screened porch, formal dining room, and kitchen filled with smells of baking bread and roasting meat.

Once a story is more or less in place, historical research comes into play. It can provide an anchor, a sort of proof that life and fiction intersect, however briefly. Today’s hunger for the real demands evidence, as though science had bled over into fiction. Critics and interviewers almost always ask writers if their stories are based on personal experience, and fictional movies often demonstrate a documentary base with archival footage or stills. I share not only hunger but delight at this intersection, as when Barbara Kingsolver, in Poisonwood Bible, grounds a fictional telling in a central factual chapter, telling the history of the CIA’s collaboration in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in Congo, with names named and dates cited.

When I decided to take Henriette to Scottsboro, Alabama, to protest the unfair trials and repeated convictions of nine young African-American men accused of raping two white women, I had to immerse myself in the long and convoluted history of this miscarriage of justice, which did not end until Governor Wallace pardoned Clarence Norris (the last still alive) in 1956, and the Alabama Board of Pardon and Parole pardoned others posthumously in 2013. When I found a telling quote, like Wade Wright’s summation for the prosecution in the second Scottsboro trial, where he said, “Show them, show them that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York,” it begged to be included. Whenever I found a luscious detail that gave the feel of real, I reshaped the writing to rope it in. The fact reworked the fiction, but the fiction also transformed the fact, altering it until the two could not be told apart. I wanted readers to learn this history, this ancestor of today’s racial abuses as well as the struggle against them, and I had to find the complex balance between Henriette’s motivations and my own.

It turned out I’d been too fearful of facts. When Fomite Press accepted my novel, editor Marc Estrin suggested that it would have broader scope with the addition of more historical material. I consulted desperately with fellow writers about whether I would lose the story (they thought not) and then read some excellent historical novels, like Colum McCann’s TransAtlantic and Amy Bloom’s Lucky Us. I got to work and added scenes and summaries about the 1927 execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Bonus March on Washington in 1932, the rise of Hitler, and other events of those tumultuous years. The result, I think, is a better book, and I am glad I took this final step.

It turned out I’d been too fearful of facts. When Fomite Press accepted my novel, editor Marc Estrin suggested that it would have broader scope with the addition of more historical material. I consulted desperately with fellow writers about whether I would lose the story (they thought not) and then read some excellent historical novels, like Colum McCann’s TransAtlantic and Amy Bloom’s Lucky Us. I got to work and added scenes and summaries about the 1927 execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Bonus March on Washington in 1932, the rise of Hitler, and other events of those tumultuous years. The result, I think, is a better book, and I am glad I took this final step.

Maggie is the author of The Crack between the Worlds: A Dancer’s Memoir of Loss, Faith and Family, published by Wipf and Stock. She received an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and has published fiction in The Sun, Nimrod, Rosebud, Paper Street and others. A chapter of her memoir, published in ACM/Another Chicago Magazine, won a Literary Award from the Illinois Arts Council and a Pushcart nomination. A story published in Rosebud and judged by Ursula Leguin won an honorable mention in their fantasy fiction contest. Her essays have appeared in America, Image, Writer’s Chronicle and elsewhere. Her first novel, A Free, Unsullied Land, is forthcoming from Fomite Press, November 1, 2015.

[…] In today's guest post, author Maggie Kast (@tweenworlds) discusses the role research plays in the development and evolution of a historical novel. […]

I am anxiously awaiting this book! I have read and re-read the Crack Between Two Worlds and love Maggie’s sensory writing. Having just lost my mother a month ago, I especially look forward to this story of this amazing woman and the times in which she lived.

Jane, I didn’t know about your mother. I am so sorry. Thank you for your kind comment!

I love learning something new in a novel.

I do too. Remember reading the Rabbit books of John Updike and finding the history running through them?

This post just SINGS. Thank you Maggie Kast for the music that composed both in this post and on the page. Thank you for generously sharing your process.

Thank you for listening so closely! I try to write for the ear, my own and others’.

I am so intrigued by Maggie’s insight that fact reworked fiction but fiction also transformed fact. I look forward to the reading at Children and Women First!

I do too and look forward to seeing you. Yes, after a while fiction and fact flow together, at least in fiction (not allowed of course in journalism or other non-fiction).

[…] An author describes how she turned her mother’s letters into a novel. […]

I so enjoyed Maggie’s flow of words into currents of ideas, and very much look forward to her novel! The interplay of fact and fiction (neither of which can exist in any pure form) creates the fabric of our ever-evolving life stories.

Thank you Joan. I agree. Things we imagine and realities we encounter intersect all the time.