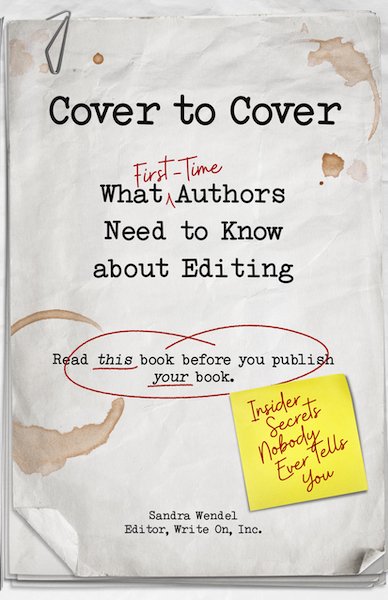

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from the new book Cover to Cover: What First-Time Authors Need to Know about Editing by Sandra Wendel.

Editors disagree about many of the finer points of their work such as whether to capitalize the word president (no, generally, but yes with President Lincoln), whether to spell out numbers (some styles say yes to every number lower than 10 or lower than 100), or whether to use the serial comma that preceded this clause (Chicago Manual of Style says yes). Some purists would argue that this post’s headline should read among instead of between. But I digress.

Editors also disagree about whether to start a sentence with And. And of course editors disagree about what constitutes the levels of editing that are often labeled copy editing, line editing, and proofreading—or just simply editing.

For guidance, I turned to the authority, the Chicago manual. Yet even that widely accepted all-knowing guide doesn’t make a distinction among editing levels: “Manuscript editing, also called copy editing or line editing, requires attention to every word and mark of punctuation in a manuscript, a thorough knowledge of the style to be followed, and the ability to make quick, logical, and defensible decisions.”

New authors are often confused about what level of editing they need, and rightly so. I hope to offer insight into the differences between line editing, copy editing, and proofreading.

[Note from Jane: If you’d like to learn about development editing and content editing, which should come before copy editing, line editing, or proofreading, please see this comprehensive post on finding an editor.]

What to Expect with a Line Edit

In a line edit, an editor examines every word and every sentence and every paragraph and every section and every chapter and the entirety of your written manuscript. Typos, wrong words, misspellings, double words, punctuation, run-on sentences, long paragraphs, subheadings, chapter titles, table of contents, author bios—everything is scrutinized, corrected, tracked, and commented on.

Facts are checked, name spellings of people and places are confirmed. This is the type of edit I perform most often.

Your editor will likely do the following:

- Conduct heavier fact checking (for example, exact titles of movies in italics, death date of a famous person in history, the protagonist was using an iPhone before they were invented).

- Make suggestions about moving or removing text (or actually doing the task and explaining in a marginal note why).

- Initiate a discussion about why the dreary Introduction could be cut.

- Offer a new scheme for moving a chapter or two around to better accommodate a time line. (Actually doing the moving and writing transitions might fall into the category of developmental edit or left to the author to do.)

- Query the author in a marginal note about why Susan in chapter 2 was wearing a winter coat when the scene takes place in summer. Or whether the author intended for the detective described earlier with a full beard to be scratching his stubble.

- Point out repetition and inconsistencies in the story line. But not rewriting. Actually revise awkward sentences, break up long sentences, streamline sentences with clauses and parentheticals. Recast sentences that begin with There are and It is. Those constructions are simply not strong. That’s why line editing is considered a sentence-level type of edit.

- Substitute stronger words for the commonly overused words (very, pretty, things, great, and good are my pet peeves).

Let me show you what an edit can do. This is a paragraph from Chris Meyer’s book Life in 20 Lessons. Chris is a funeral home director. A line edit would turn this rough paragraph—

The more regular are the things that make life so cruel and unfair: a healthy man has a heart attack on his bike ride, a child stricken with cancer, a mother dying before her children reach middle school, a father on vacation with his children, a son abalone fishing because it brings him joy, a daughter in an auto wreck with her best girlfriends, a simple slip and fall, gunshots, the list is as endless as it is tragic.

—into this:

More likely are the events surrounding death that make life so cruel and unfair: a healthy man has a heart attack on his bike ride; a child is stricken with leukemia; a mother dies before her children reach middle school; a father suffers a fatal stroke while on vacation with his children; a son drowns while abalone fishing; a daughter is killed instantly in an auto wreck with her best girlfriends; a simple slip and fall, gunshots, the list is as endless as it is tragic.

What to Expect from a Copy Edit

When an author says, “I just want a copy edit,” I ask what they mean. Again, there is confusion about what a copy edit includes. Most of the time, authors want that thorough line edit. If a manuscript is so clean, so squeaky clean, so perfectly written with lovely paragraphing and fine-tuned punctuation, then maybe the manuscript just needs a copy edit. Like never. I can’t even recall a manuscript that has come to me this clean that it would need just one pass for a polish for mechanical issues. Never. Not even books written by professional writers. And not even my own book. I hired out my line editing, and it’s a humbling process.

So let’s just agree that when someone says copy edit, they really mean a much deeper and more thorough edit than putting commas in the right place. A copy edit is the lowest level of edit. Rarely does a manuscript need “just” a copy edit. Sometimes a copy edit is a final step performed separately by your editor or someone else with fresh eyes. Some editors (like me) do copy editing all along looking for these types of errors, and a copy edit is part of the line edit.

Here’s my simple checklist:

- Correct any typos, which would include misspelled words.

- Fill in missing words.

- Format the manuscript before production, and that includes just one space between sentences (I don’t care what you learned in typing class in high school, the double space messes up the document when it is converted into real book pages).

- Streamline punctuation and properly use commas, periods, and em dashes—like this.

- Avoid overuse of ellipses to denote a break in thought … when they are really used to show missing text. And those exclamation marks! I allow authors about five in each manuscript. Overuse them, and they lose their punch.

- Make sure the names of characters and places are spelled consistently throughout (Peterson in chapter 1 may or may not be the same Petersen in chapter 6).

- Find and replace similarly sounding words that have different meanings (for example, effect and affect).

- Conduct a modest fact check (perform a Google search to find the exact spelling of Katharine Hepburn or the capital of Mongolia). This isn’t Jeopardy!, so you do get to consult resources. I keep a window open to Google just for such searches.

- Make new paragraphs to break up long passages.

- Question the use of song lyrics and remind the author to get written permission.

- Point out, in academic work, that footnote 6 does not have a reference source in the citations.

- Remove overuse of quotation marks. For emphasis, use italics, but sparingly. Books generally do not use boldface.

- Impose a consistent style for the text (this means using a style guide for capitalization and hyphenation, treatment of numbers, heading levels). The Chicago Manual of Style is preferred unless the work needs to conform to an academic convention such as APA, AMA, or MLA.

What to Expect from a Proofread

Let’s say your manuscript is fully edited (no matter which level you chose, sometimes even a developmental followed by a line edit with the same or different editors). Your work will need a proofread either in manuscript format or after it is designed in pages as PDFs.

Should you proofread your own work? The short answer is later, if you’re in writing mode. The shorter answer is never. Why? Because it’s your work. And your brain plays funny tricks on you. It will fill in your words, and you’ll be completely shocked when a professional editor returns your edited manuscript. What? How could I miss that?

Most editors won’t admit this, but we, too, miss things. We’re human (or many of us are). So the question on the table is when to proofread.

I prefer to hire proofreaders to proof for absolute error when the manuscript is in final pages or PDFs. But you can also proofread before it goes into production (and into PDFs), just knowing that you do need another proofing of the PDFs.

Use a different person, a different editor, even someone who is a professional proofreader. This person brings a fresh set of eyes to the work and scours for absolute error such as name misspellings, wrong URLs, bad URLs, numbers that don’t add up in a table, double words, missing words, and those crazy stupid errors you as the author have missed and your editor missed, and you question your sanity. Those errors.

A proofreader doing the proofing at the PDF stage will look for all these types of errors plus others: bad word breaks and hyphenation at the end of a line, hyphen stacks (many words hyphenated at the ends of lines, stacked), widows and orphans (single words or lines at the top or bottom of a page), wrong captions with photos, page numbering, missing and misspelled headers and footers, page numbering matches with the table of contents, lines too tight or too loose. Many of these production issues are introduced as pages are created.

Proofreading is not the time to revise, rewrite, and delete. Your interior page designer might actually kill you. At the very least, major changes in proofing in PDFs can be time intensive and expensive. Put in the work way before you see your baby in actual page layouts.

Parting Advice

As Random House copy chief Benjamin Dreyer said in his exceptionally fascinating book, Dreyer’s English, “My job is to lay my hands on that piece of writing and make it … better. Cleaner. Clearer. More efficient. Not to rewrite it … but to burnish and polish it and make it the best possible version of itself that it can be.”

In editing world, even if editors disagree on what constitutes certain types of editing, we do agree that your manuscript deserves a professional and sound edit to make it free of typical errors of spelling and punctuation, with proper use of the right word, judicial paragraphing, logical chapter breaks and chapter titles, and prudent fact checking for accuracy—and, above all, consistency.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Sandra’s new book Cover to Cover: What First-Time Authors Need to Know about Editing.

Sandra Wendel, a nonfiction editor of award-winning business/leadership, memoir, true crime, and self-help books, is the author of the new book, Cover to Cover: What First-Time Authors Need to Know about Editing, and the moderator of the Facebook page: FirstTimeAuthorsClub. Find out more at her website.

Great post. New authors might also need to understand substantive editing—the process of looking at an entire manuscript and commenting on structure, narrative arc, pacing, character development, etc. Line editing, copy editing, and proof-reading come after the substantive edit, which is usually where the editing process starts. Does the book begin and end in the right place? (Astonishing how often the first and last chapters can be cut. I once had the unpleasant but highly effective task of telling an author her book started on page 93.) Are all the scenes in the right order? Is that bit of background really necessary or could it be dispensed with in a well-placed scrap of dialogue? Are characters well introduced and do they develop through the story? Is the tone consistent throughout? Is the pacing compelling throughout? Often, the substantive edit results in no marks on the manuscript but rather, a long editor’s note that points out weaknesses and strengths and possible solutions. Excellent line editors and copy editors abound, but skilled substantive editors are thin on the ground, and a godsend to writers, whether new to the writing world or veterans.

Love this!

[…] on the definitions Jane Friedman uses in her article (https://janefriedman.com/the-differences-between-line-editing-copy-editing-and-proofreading/), my editing involves a blend of line and copy editing, with some Word formatting magic thrown in, […]

There’s never any end to an edit. I say it like that because I just finished a most curiously funny novel called “Never any End to Paris,” which turns out to be much about writing. By the Spanish writer, Enrique Vila-Matas. But back to editing … I’m currently conducting my wife’s brilliant novel through the editing process, and successfully convincing her that it’s money well spent to send the ms through all these levels of edit. With a self-pub book, it’s not about the money, but about giving birth to the best off-spring possible. Almost done. Proofreading next. There’s never any end to worrying about that hidden typo.

[…] is necessary for our work to reach that professional level. Sandra Wendel reveals the differences between line editing, copy editing, and proofreading; Patti Callahan Henry describes self-editing by ear, and Terry Odell urges playing tricks with […]

Fantastic article and genuinely clarified some elements for me. Thank you!

I really wish authors would understand the critical importance of hiring someone else to do the editing. If you want to improve yourself, and your writing, this is what you need to do.

[…] The differences between line editing, copy editing, and proofreading from Jane Friedman […]

I’ve read four different articles explaining the difference between line edits and copy edits, and I’m still confused. One article conflated the two within the same article (maybe the writer needed another edit or two), and the rest all seem to contradict one another.