Today’s guest post is by writer Katrina Byrd (@ovenhot).

A few years ago, I sat in a dining room surrounded by friends as Reggie Robertson explained the business model for Robertson’s Metals and Recycling, a business he and his family own in Dickinson, North Dakota. “We have a fair markup.” He explained their process of market research and other requirements of the business. “We maintain our equipment.”

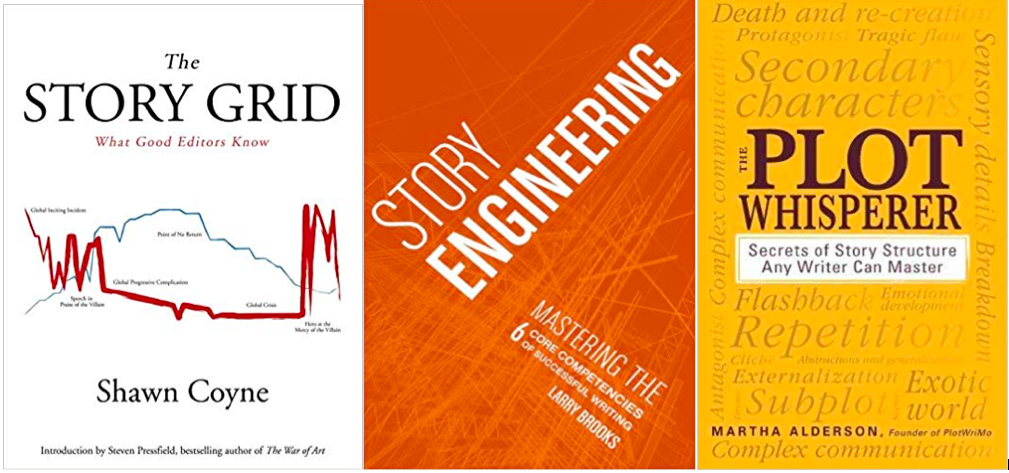

This was the first time I thought of my writing as a business. As a writer, I stay up to date on literary trends. The equipment I maintain is my computer and software. My inventory is my writing (short stories, plays, films). Creating works in line with industry standards requires developing ideas, understanding industry standards and studying plot and structure; recently I read three books on novel planning:

- The Story Grid by Shawn Coyne

- Story Engineering by Larry Brooks

- The Plot Whisperer by Martha Alderson

“But I Don’t Like Writing According to a Formula!”

Some writers consider themselves what Larry Brooks calls an “intuitive” writer: people who rarely want to work according to a blueprint and cringe at the thought of following a “formula.” But, Brooks says, “If you don’t know what you’re shooting for, if you just make stuff up as you go without much if any forethought, it probably won’t work.”

Moreover, plot and structure books aren’t necessarily calling for adherence to a formula—in fact, they warn against it. Coyne discusses, for instance, the amateur writer: “Despite all of their desire to live by their own lone wolf ways, ironically what amateur writers really want is a recipe.” Amateur writers want to emulate writers on the bestseller list with no consideration for the various ways one can get on that list. They put money ahead of the story, and this makes them their own worst enemy.

One of the values of all three books (and their methods) is that they provide a means of testing whether a story works on a professional level, at any stage of the process.

- Plot Whisperer offers a plot planner, which consists of seven plotting questions, as well as a character emotion profile. Alderson recommends crafting a character emotional profile on the protagonist at the beginning of a story then again at the end. This information is used to create the universal story, which is placed on a line graph.

- In Story Engineering, Brooks’ fundamental concept to story planning is the six core competencies. A writer may start with a great story idea and great characters, but without considering fundamental elements like backstory, stakes, and inner landscape, the story may fall flat, or run into other challenges such as bad pacing and lack of a compelling character arc.

- Story Grid is a tool to aid in becoming your own editor. Labeled with critical information about the global story, the spreadsheet identifies what is working and what isn’t. “It is like a CT scan that takes a photo of the global story,” Coyne writes.

But Do Formulas Work for Literary Novels?

Broadly speaking, there are two literary cultures: literary and commercial. An author needs clarity on what she’s writing to understand how to successfully structure her story. Alderson, Brooks, and Coyne all agree a review of the story’s scenes is a crucial factor in determining the appropriate literary culture.

In The Plot Whisperer, Alderson says stories tend to be action driven or character driven. Scenes at the beginning and at the end of her plot planner help determine story type. High action and a dramatic climax close to the end typically indicates an action-driven story. When a character uses new skills to conquer her greatest antagonist, then the story may be character driven. “If the characters show transformational behavior during a high-action climax, likely your story is a balance of the two plot structures,” Alderson says.

Brooks suggests that in literary fiction, scenes are character driven, while in commercial fiction, scenes are action driven. “Writing literature vs. commercial fiction is a choice a writer can make,” Brooks says. According to him, the key to mastering either style is a solid understanding in the mission of each scene.

According to Coyne in The Story Grid, the commercial culture consists of genres which, in themselves, bring about “obligatory” scenes. For example, if your story is a romance, there are specific scenes it must possess to fit into this category. Coyne uses the story grid approach to help writers identify these scenes before the story is written. Then, once a story is complete, the story grid serves as an editing tool.

According to Coyne, a desire for the “glamorous aspects of literary trade” hinders some novice and seasoned writers from seeing the value of the story grid. According to Coyne, many writers embrace “the thrill of dashing off chapter after chapter in a white heat of inspiration, etc—and they undervalue the blue collar aspects of story construction and inspection.” Coyne designed the grid as a tool to bridge the gap between “commercial necessity and literary ambition.”

Personally, I recommend The Story Grid to authors interested in a guide for long-form narratives. Coyne offers information on structure, editing, and the publishing world. As a recent MFA graduate from Mississippi University for Women, I have a 260-page novel in need of some revision. By putting my global story on the spreadsheet, I got a deeper understanding of how an editor would view my novel. While my novel has a clear inciting incident; strong characters; dramatic action; and a clear beginning, middle and end; my plot points were slightly off the mark. A few of my scenes were obtuse, and in some back-to-back scenes, there was little variation in how the scenes turned or shifted. In four back-to-back scenes, I used dialogue at the turning point.

But the story grid tool is also invaluable at the beginning stages of crafting a novel, and knowing the literary culture in which your work aligns puts you ahead of the game.

What story planning methods do you use? Share with us in the comments.

Katrina Byrd, a writer/playwright, is a 2018 MFA graduate of Mississippi University for Women. Byrd’s short plays appeared in several theatres including Vicksburg Theatre Guild, MOLJOAA Performing Arts Company and Bay St. Louis Little Theatre. Featured in literary magazines across the country, her fiction centers on strong female characters who overcome insurmountable obstacles. You can find Byrd’s fiction pieces in The Disappointed House Wife, Black Magnolias Literary Journal, and Kaleidoscope. Due to an internship funded by the Mississippi Department of Rehabilitation, Byrd, visually impaired since birth, was hired to write this review for JaneFriedman.com. At AWP 2018, Byrd also interned with Jane Friedman to provide content for the blog at The Business of Being a Writer website. Byrd is also a 2018 Mississippi Arts Commission Artist mini-grant recipient. Connect with Katrina at Facebook and on Twitter at @ovenhot.

I put Layer Your Novel together because I had not seen anyone teach the most simple and intuitive method for structuring a story. As with framing up a house, writers do best to start with the key foundational scenes first, get them in the right spots, then build on them.

These other methods are terrific (I often tout Larry’s and Martha’s methods and books), but they can be a bit complicated and don’t lay out as clear a road map (IMO) as this layering method. I also provide charts on how to construct various second layers (of the next 10 scenes) for action-reaction, subplot, and romance methods. All info can be found on this layering method as well on my blog Live Write Thrive.

My apologies if this sounds like self-promotion. Just offering an additional perspective to those who may want something possibly more approachable and laid out step by step with breakdown examples from novels of various genres. Happy writing!

C. S. Lakin, thanks for your comments. Your zeal to help writers present their best work comes through loud and clear. Knowing key scenes and their proper placement is a valuable tool especially at the beginning of the writing process. I look forward to hearing more from Live Write Thrive.

As to the three books reviewed in the article, they all have valuable information for writers of all levels. Though different in presentation of information, they all stress the importance of structure to organize, shape and direct creativity.

Again, thank you for your comments. I look forward to hearing more from you!

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

🙂 You’re welcome.

I love writing craft books! I’ve read (and re-read a few times) Larry Brooks’ Story Engineering and found it useful as a “thinking” aid. (I’m a plotter/pantser hybrid.) I own the Plot Whisperer Workbook but need to confess that I’ve not delved too deeply. Now I’m intrigued by the Story Grid and have just signed up to receive updates from Mr. Coyne’s website.

One of my most-used craft books is Romancing the Beats by Gwen Hayes. As a romance author I find it useful for plotting out the stages of falling in love, and out of love, and back into love, hehe. At the start of every writing project I read portions of Story Genius by Lisa Cron which helps me discover my protagonist’s back story and inner wound/misbelief. I’m also a fan of the craft books written by James Scott Bell and Donald Maass – excellent information in every one.

Great post – thank you!!

Cheers.

Thank you so much for your comments. I am glad you’re intrigued by the Story Grid. I hope Coyne’s technique is useful to you. I was drawn to it because I liked the idea of putting my entire novel on a spread sheet. With this view, I can determine weak spots. I also love this method at the beginning of the writing process. Knowing the direction of a novel at the beginning of the process makes the writing process easier for me.

Thank you.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

Luanna, I’m a big fan of Story Genius and most anything by Donald Maass, as well. Although I find Coyne’s The Story Grid system daunting, I love The Story Grid podcast.

Sandra, I will have to check out Story Genius. Sounds interesting.

I always want to know what my characters want and where they want to go before I can plot. And so I write what I call “The Zeroth Draft” where I splurge the story onto paper as soon as I know the ending. Then I plot it, card it and often find a new and better ending, and THEN I write the 1st draft.

I LOVE the term “The Zeroth Draft.” Thank you for sharing your process.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

Always good to ponder our writing with these questions of structure and intuition. In the end I think it comes down to our innate sense of story… and for this reason I can’t help but think that reading reading reading is the key. Don’t we all charge into a new story armed with a “sense” of how a story goes. I’m convinced that the “heart” of the story is all important. At some point in the writing I get serious about how the story turns at the Act II crisis… and if that’s not deeeeeeply satisfying, I suspect that the reader doesn’t get their money’s worth. For that reason, I see many stories actually end without a climax… because the protagonist’s radical change of heart means more than any prize that Act III might bring. What say ye?

Thank you for your comments.

For me reading is key to structuring my creativity. Many of my creative story ideas failed due to my lack of understanding of story structure. Reading across genres helped me to understand audience expectations in specific genres. Reading was also key to how and what I write.

As to your question about the protagonist’s change of heart, I think a writer needs to consider which literary culture with which her story aligns and audience expectations of that culture. What I liked most about reviewing these books is that they urge you to look at your writing the way industry professionals view it.

Again, thank you for your comments.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

You have given me so much to work with! Can you give me ideas of how to design a memoir-travelogue? I’m working on an Africa portion: a member of my group falling in love with a Tuareg in the Sahara and later our group being arrested by a self-proclaimed emperor for stealing his fan belt. (This is nonfiction.) I am an admirer of Twain’s travelogues.

Hi, Steve, so sorry for the delayed response. Travel writing isn’t my specialty, so I have to do a bit of research before offering tips on design etc. Your project sounds very interesting! I will do some research then reply to your question in about a week. Thank you for your comments. I flounce my boa at you!

I really enjoyed Cathy Yardley’s Rock Your Plot and it, too, has a workbook. If you’re looking for another book to add to the way you think about plotting, I reviewed it a couple of years back on my blog: http://www.laurakcurtis.com/2016/03/rock-your-plot-by-cathy-yardley-a-tbr-challenge-read/ The grid system sounds really cool. I will be looking at it!

Thank you for your comments.

Rock Your Plot is now on my reading list. I enjoyed reading your review. I hope The Story Grid is useful for you.

Thank you.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

Great post for a story structure freak like me. My post, below, on Brooks’ site details just how valuable Story Engineering has been to me. It ends with a link to the graphic resource I created to help other writers implement Brook’s approach. Larry included my “Novel Blueprint” based on his principles in his follow-up how-to tome: Story Physics. http://storyfix.com/engineered-for-success

Wonderful post on Storyfix.com, Bryan, and an awesome graphic.

Hey, Bryan, this is an excellent article and I love love your novel blueprint. Is it available to use for teaching purposes? I flounce my boa at you!

I found The Story Grid as I was writing my memoir. It was helpful in pacing the story and treating real life like a novel. In the end, I think it helped me find the type of story I was telling and frame it in a way that would be exciting and meet readers’ expectations.

Catherine, I found this to be true of “The Story Grid” as well. Making a foolscap at the beginning of a piece, helps me to think about the story I want to tell and I’m able to shape the idea accordingly.

Keep writing!

Thank you for sharing.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

I like to use elements from a number of sources because it gives me options that work differently in different parts of my book. I took a weekend retreat once with Martha Alderson and her business partner Jordan Rosenfeld and bought her Plot Whisperer book and workbook, both of which have been helpful. I’ve also used parts of Stuart Horowitz’ Book Architecture series and Randy Ingermanson’s Snowflake Method

Thank you for your comments! Yes, using several books is a great as well. I flounce my boa at you!

I love John Truby’s Anatomy of a Story. Technically, he started as a screenplay doctor/analyst, but then branched into larger “story.” What I like about it most it is follows a model where character and plot are two sides of the same coin, and hits all the elements (22) that are required to make a story resonate as complete:

1 self-revelation/need/desire

2 ghost/context,

3 problem/moral need

4 inciting incident

5 overall desire

6 allies

7 opponent/mystery

8 opponent/ally

9 first revelation

10 plan

11 opponent’s plan/first counter attack

12 drive

13 attack by ally

14 apparent defeat

15 second revelation /decision ; obsessive drive, changed desire/motive

16 audience revelation of opponent’s ally

17 third revelation/decision

18 gate/gauntlet

19 battle

20 self-revelation

21 moral decision

22 new equilibrium

This provides the minimum basics of what needs to happen in a story (screen or novel), except that in a novel you have have as many revelations as you want as long as they continue to escalate the stakes.

Patricia, I will add this to my reading cue. Thanks for sharing.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

Great post, great suggestions. Thank you. I’m in the thinking/mulling/plotting stage of writing my 7th novel, and each time it’s like going back to basics.

I discovered Story Genius this year and it has really helped. It’s brilliant.

I’ve long been a fan of Save the Cat by Blake Snyder for plot essentials, but I’ve recently done a deep-dive into Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. It’s fantastic. What I especially appreciate is that she shows how an outline and even the genre can change throughout the writing process.

I love The Story Grid podcast, but I find the book and Coyne’s system daunting, especially since one of the first steps is to identify the “obligatory” scenes of your genre. This can be a challenge! Coyne identifies the obligatory scenes of some genres — i.e. thriller — but not of others. (It’s possible that he has added these details since.) This dialogue inspires me to go back to The Story Grid and give it another try — although my personal feeling is that it’s likely best after a first or second draft has been written.

At this early mulling stage, I also return to the essential characters of story as outlined in The Writer’s Journey; Mythic Structure for Writers by Christopher Vogler: the hero, the mentor, the herald, the shape-shifter, etc.

Again, thank you for this blog post. The comments, too, have been great. I’m checking out the recommended books.

Sandra, I’ve never read “Save the Cat.” I will add this to mu reading cue along with the other titles you’ve mentioned.

Thank you for your comments.

I flounce my boa at you!

Katrina

🙂 I’m all over boa flounces, Katrina! Go for SAVE THE CAT WRITES A NOVEL — it’s even better than SAVE THE CAT, imo.