In this interview, author Elinor Lipman discusses writing effective humor and non-dialoguey dialogue, how she gets readers to see her characters without describing their looks, rejection, and the book that became a Helen Hunt movie.

Elinor Lipman (@ElinorLipman) was born in Massachusetts and is the author of more than a dozen novels. Her first one, Then She Found Me, was published in 1990 and was adapted into a film starring Helen Hunt, Bette Midler, and Colin Firth. She won the New England Book Award in 2001, and her novel My Latest Grievance won the Paterson Fiction Prize.

She lives in Manhattan, as well as in upstate New York.

KRISTEN TSETSI: In 1981, your first published story (possibly the first short story you wrote?) appeared in Yankee Magazine, and then your first collection of stories published six years later, followed by the publication of your first novel three years after that (a novel that would later be optioned and, much later, adapted to film). Until Rachel to the Rescue, you’ve said, not a single book of the fourteen (I apologize if I missed any) you’d written had been flat rejected by publishers. (More on that later.)

There’s something about what you have to say and how you say it that clearly connects not only with readers, but also with the people who judge what readers want and what’s marketable. What do you think it is about your writing that appeals to people so broadly?

ELINOR LIPMAN: My first published story, “Catering,” wasn’t my first story; I think it was my fifth or sixth. Rachel to the Rescue is my 13th novel/16th book. As to their appeal—I often hear that they offer comfort by being funny but not brittle-funny; warm-funny. I do believe in happy endings—I mean, if I’m the god of this world, why would I make my characters suffer?

What changes in the publishing industry, if any, have been apparent to you since you began publishing, and how, if at all, have you had to adapt as an author?

Ebooks, audio books, social media. Even email didn’t exist when I was first writing books. I’ve had to adapt by getting myself onto those platforms, and I wouldn’t mind if they all disappeared. I’m always trying to gauge how much me-me-me my followers can tolerate. I grew up with a father who often said, “Self-praise is no praise at all.”

You say on your website that you only endorse books you genuinely love. What does any book that comes into your life need to have or be in order for you to love it?

I love wry writing, a gripping story, sympathetic characters, intelligence, no clichéd language, no reaches for poetic descriptions that feel self-conscious. I like wacky but believable. I love Steve McCauley, Maria Semple, Tom Perrotta, Mameve Medwed. The late Carol Shields was a huge favorite.

On the art of writing humor, you’ve said, “I’m not consciously trying to make jokes. If I sense I’m making a joke per se, then out it goes.”

It can be hard to not be trapped by moments of wanting a character to say something funny, writing the quippy dialogue, and believing it should stay in the story because it made you, the writer, laugh. How do you recognize when you’re telling a joke for the joke’s sake rather than creating organic humor, and how do you stop doing that?

I don’t try to make jokes, so it’s hard to answer the when and how of that. I’d say that what I always try to find is the better, stronger word, and often that word or phrase makes people smile. Henry James called the opposite of that “weak specification.” I rewrite and polish, then polish some more, trying to sharpen the sentences. I think it’s the sharpness that makes people laugh.

I don’t laugh when I’m writing and am usually surprised at what people find funny. I once looked up at a reading and asked the audience what was funny about that particular sentence they’d just laughed at. Someone answered, “We identified with it. It was a laugh of familiarity, which makes it a comedy of manners.”

I just read a novel (truth be told, didn’t finish it) where every character spoke with what I consider a West-Wing (i.e. dialogue by Aaron Sorkin), too-quick wit that came fast, that was wise-cracking in such a way that I thought, No one speaks like that every time, let alone every character one encounters. It seemed funny in a brittle way that said “This is dialogue” more than “This is two people talking in real life.”

Rachel to the Rescue incorporates a good amount of dialogue between Rachel and her parents in its early pages. Through their distinct ways of speaking to each other, their conversation introduces readers to the family dynamic, the parents’ personalities, and tucked inside all of it are some background details of Rachel’s life.

Many Amazon reviews about your novels praise your use of dialogue, and as a reader, I love a lot of good dialogue. But as a writer, what makes you enjoy writing it, and what dialogue-writing tips can you offer writers who might struggle not only with writing it, but also with how best to use it?

Dialogue is the easiest thing for me to write. I have to remind myself to let the characters pause, to take a sip of water, to notice their surroundings. An editor once wrote in the margin of a page, next to a long exchange, “Could someone here please pass the potatoes?”

I might not always succeed, but I try to give the dialogue the feel, the timing, the pacing of real-life conversation: the hesitations and the physical gestures. Also, I try to get into the scene as late as possible and leave it as early as possible, eliminating the hello-how-are-yous.

And third piece of advice—watch out for direct address when two people are talking. Newer writers often have their characters saying things like, “Well, Mary Jane, would you like to watch the news?” (In real life, it’s rare to use direct address in casual conversation.) Don’t worry about the “he-saids” and the “she-saids.” You don’t have to think up new attributions, because the readers’ eye skips over those, anyway. They become invisible.

And lastly, do NOT plant information in dialogue; i.e., do not have a character say over dinner, “I very much like the new sales job I recently started at a car dealership in Fair Lawn, New Jersey.”

Your description of your mother in your essay collection I Can’t Complain: (All Too) Personal Essays is captivating for its tiny, mundane, fascinatingly unique details that individualize the person who was your mother.

“She gave birth to me, the second child, at forty-one. My birth certificate lists ‘mother’s age’ as thirty-four, and it wasn’t a clerical error. […] Her bed slippers were mules, and her French twist required hairpins. […] …she didn’t like drinking water out of mugs.”

These are the same kinds of observations that lend authenticity to fictional characters. How do you select your details?

Your question made me smile. Nonfiction is one thing, such as those details above, but I have to push myself to describe things in fiction. I let the reader imagine what the character looks like—and they do.

I give the minimum description, maybe one or two things that help the reader see the character and the place. In The Pursuit of Alice Thrift, I gave a male nurse in the neonatal unit a toy koala bear clinging to his stethoscope and mentioned that his cheeks were acne-scarred. Interestingly, reviewers almost always described him as handsome, which was their take-away from what I saw as his goodness. In Good Riddance, I gave the male love interest braces and described his living room with no more than its couch.

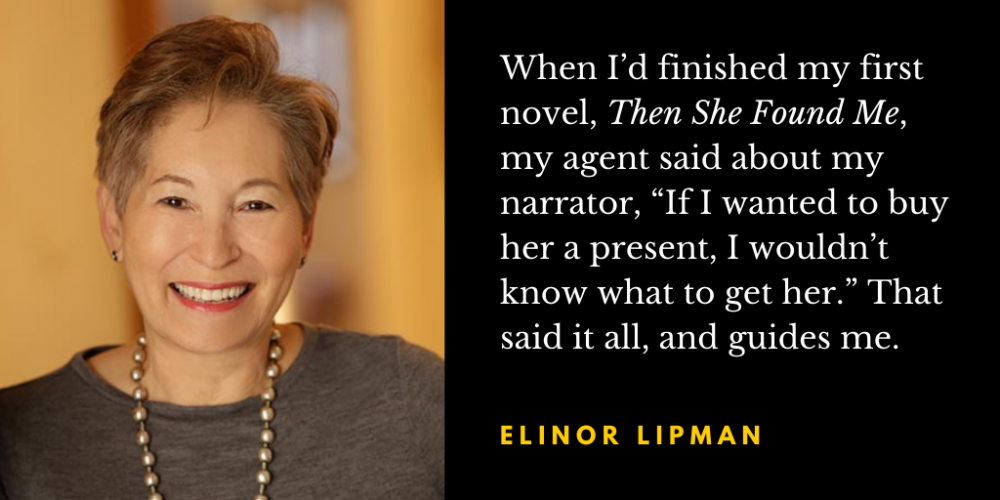

When I’d finished my first novel, Then She Found Me, my agent said about my narrator, “If I wanted to buy her a present, I wouldn’t know what to get her.” That said it all, and guides me: What’s in her room? What does she wear or how does she adorn herself? Give the reader that much.

But I dislike long passages about the weather, the sky, the flowers. To quote the late, great Elmore Leonard, “I try to leave out the parts that people skip.”

In 2003, five years before Then She Found Me would release as a movie starring Helen Hunt, Bette Midler, Colin Firth, and Matthew Broderick, your novel had already been in adaptation limbo after having been optioned many years before. “My son was in first grade when Then She Found Me was optioned and then bought by Sigourney Weaver. He’ll graduate from Columbia next year,” you said at the time.

I’m curious to know more about this experience. Before it was first optioned, had you hoped for movie adaptations of your work? And once the 19-year wait was over and the movie was being made, what was that like? I don’t mean your feelings about how loyal the screenplay was or wasn’t to the novel, which you addressed in the Huffington Post, but purely the experience of the adaptation taking place. Had it been such a long, slow process that it was anticlimactic, or did the reality live up to whatever you might have imagined? And what did you imagine?

Six questions! I’ll be brief. (Plus I wrote about the movie experience in my essay collection.)

I hadn’t hoped or known that manuscripts were circulated to producers, so that was a big surprise. There was the long dry spell when I gave up hope of it ever being made. Once I realized that it had gone into Helen Hunt’s hands (clued in by an email my son, then graduated from college and working at the Wm. Morris Agency, saw), it moved along.

I heard about the casting. I corresponded with Helen and met her; I visited the set and went to the premiere. I didn’t mind that the movie departed from the book because I loved the movie. I’d been advised by Meg Wolitzer, when the manuscript was first optioned, to think of it “as a movie based on a character suggested by the novel.” It was excellent advice.

In an essay titled “My Book the Movie” (published in the collection I Can’t Complain), you wrote:

Decades ago, on an unseasonably cold and rainy May morning, my phone rang, and it was Hollywood calling. “How would you feel on this miserable day to know that Sigourney Weaver loves your book?” this agent asked. She was talking about my first novel, Then She Found Me, and even though I surely knew that books could be turned into movies, I had no idea that mine had been circulated to producers. My husband and I threw an impromptu party to which I wore, aiming for Hollywood-tinged irony, a strapless dress, a rhinestone bracelet, and sunglasses.

I think many authors fantasize that having a book adapted to screen would mean a substantial increase in that book’s sales due to new, or renewed, interest in the novel. How did the movie impact sales of not only Then She Found Me, but your larger body of work?

The movie-tie in edition of Then She Found Me did hit the NY Times bestseller list, but not even in the top 20 (the part you don’t see in the newspaper).

Has it helped sales in other books? I never ask about sales. It’s a matter of “know thyself.” I don’t want to be depressed hearing a number that will disappoint. And if there is good sales news, you get it, something like “going back to press.”

My goal is to do well enough that my publisher wants to publish my next book. I don’t need to know numbers. (One exception: the publisher of Vintage wrote me a real letter on paper when sales of the paperback The Inn at Lake Devine went over 100,000. I didn’t mind hearing that at all.

You say in an interview on author Caroline Leavitt’s blog that Rachel to the Rescue was the first book rejection you’d faced. Publishers loved it, but they were worried it wasn’t the right time for something that pokes fun at Trump; they feared Trump fatigue.

As lovely and positive as the rejections were, however, they were still rejections. What was that first-time experience like for you?

It was terrible. Each rejection was a kick in the gut. But I didn’t give up.

You went on to publish Rachel to the Rescue with independent UK publisher Eye Books, which prides itself on working with authors, allowing them to be part of the conversation when it comes to cover art, pricing, and marketing and promotion.

How would you compare that relationship and overall publishing experience to relationships and experiences you’ve had with past publishers (which include divisions of Viking, Houghton Mifflin, Simon & Schuster, and Random House)?

Another question requiring 1000 words!

Because I’ve always had terrific editors, who bought my books because they loved them, I’ve enjoyed almost every step along the way. I’d still be with my first editor (and the next one and the next one) if they hadn’t moved on.

The different and most fun part of bringing out books with my British publisher is that one person can make almost all the decisions. It was fast and painless getting Rachel out. As fast as it was, my involvement in the editorial end of it was about the same as big publishers, except I turned around the edits based on the U.K. editor’s notes and suggestions. The cover artist, Ifan Bates, who’d done the UK covers for Good Riddance and On Turpentine Lane, is so quick and so good that I loved and said YES! to his first renditions for every one of those books.

I’m more involved with promotion of Rachel to the Rescue than any other book, by far, because I wanted it to have a life over here and saw myself as the U.S. vehicle for big-mouthing it. I made the decision for the first time ever to hire a publicist to help reach readers and bloggers, the very thing that publicity departments did for my U.S.-published book. I’m very glad I did.

Thank you, Elinor.

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called a novel “for right now” and “scathing social commentary.” She’s a former adjunct English professor, former reporter/columnist/feature writer for a daily newspaper, former writing instructor, and a former editor of the literary journal American Fiction (New Rivers Press). She lives in Connecticut.

I really like it when authors with a solid reputation open up about their journey. Apparently it’s not a straight road for anyone. Gives me hope.

“My goal is to do well enough that my publisher wants to publish my next book.” Me too. But I am still new to the business, and I am working on it.

Thank you very much for this wonderful interview. I love your candour. Thank You!