Today’s guest post is from author Barbara Baig.

How do certain people become really great at what they do?

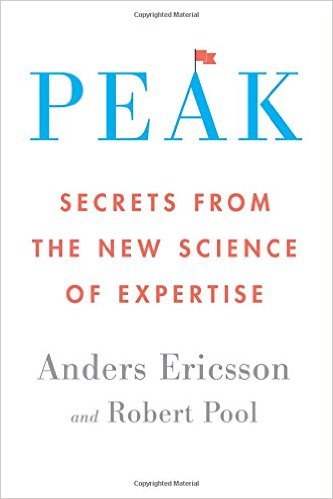

That’s the question psychology professor Anders Ericsson has been exploring for his entire career. Now, in his new book, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, co-written with science writer Robert Pool, Ericsson reveals the answer.

If you’ve heard of Ericsson, it’s probably because his research and ideas have been featured in many articles and books, notably Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and Geoff Colvin’s Talent Is Overrated. In Peak, he finally gets to explain things his own way.

In very readable prose, Peak describes how Ericsson and his colleagues have studied top performers in many fields, and it shows how all of these performers use the same kind of training methods. Peak is not designed specifically for writers, but any aspiring writer who reads it and (even more important) makes use of the training principles the book explains will find his or her abilities dramatically improved.

How can this be? How can a training approach used by top golfers, divers, ballet dancers, surgeons, and many other people possibly help writers?

The answer is simple: It’s all in our brains.

When it comes to becoming better writers, most of us make three assumptions:

The answer is simple: It’s all in our brains.

When it comes to becoming better writers, most of us make three assumptions:

- Each of us is born with a certain innate potential for achievement: We call it talent. Getting better at what we do is simply a matter of fulfilling that inborn ability.

- To get better at what we do, we just need to keep doing it.

- Improvement depends on how much effort we put in. If we’re not improving, we’re just not trying hard enough.

These assumptions are so common you might not even realize you hold them. But they share something with many other widely held assumptions: They aren’t true.

- Even brain scientists used to believe that each person’s brain—and, therefore, his abilities—was fixed at birth. But since the 1990s brain scientists have discovered that the human brain, even the adult brain, is far more adaptable than anyone ever imagined. They call this ability of the brain to change in response to challenges its plasticity, a quality that (barring injury or illness) everyone’s brain possesses. It’s the ability of our brains to change—not our innate talent—that allows us to learn and develop new skills.

- “Just keep writing, you’ll get better”: This piece of writing advice pervades the internet. Sadly, it’s completely wrong. In their studies of experts, Ericsson and his colleagues have shown that none of them achieved mastery simply by doing the same thing over and over.

- And while effort is certainly important, effort by itself will get us nowhere. What we need, Ericsson explains, is the right kind of training, the kind of training that creates experts in any field. He and his colleagues named this kind of training deliberate practice. Well, sure: practice. We all know what that is. Or do we?

When most of us think about practice, we’re imagining what Ericsson calls naive practice, the kind of repetitive action we do to learn a skill and then put it on automatic pilot. We learn a lot of things this way—cooking dinner, for instance, or driving a car. The trouble with this kind of practice is that it will never help us improve our skills. For that, we need a different kind of practice, one Ericsson calls deliberate practice. Deliberate practice, he tells us, will harness “the adaptability of the human brain to create, step by step, the ability to do things that were previously not possible.” With this kind of practice, we literally build areas of the brain involved in writing, thereby increasing our own “talent” and making ourselves better writers.

This particular kind of practice—deliberate practice—is not easy, and it’s not fun. It requires setting goals for our practice sessions, maintaining focus as we practice, getting feedback on our practice, pushing ourselves out of our comfort zone, developing effective mental representations of the skills we’re practicing, and learning from models of excellence. Peak provides details of all of these elements of deliberate practice, and lots more, giving us a totally new approach—new for writers, but well-proven in other fields—to developing our skills.

So, how might we use this approach? First, we have to consider our writing skills: Which ones do we have? Which ones do we lack?

Suppose, for instance, that we want to improve our sentences; suppose that we choose to work on prepositional phrases. First, we need to be sure we know what a prepositional phrase is (effective mental representation); we’ll probably have to look that up and provide ourselves with a list of prepositions to use in our practice. For our first practice session, perhaps our goal is to write a number of sentences and use every preposition on the list. Getting feedback on this practice is easy; we just compare the prepositions we’ve used with those on the list. (If we’re not sure we’ve used a preposition correctly, we’ll have to check that out.)

After we’ve done some more practices like this, we can push ourselves out of our comfort zone by setting stricter requirements, perhaps insisting on three prepositional phrases per sentence, or beginning and ending a sentence with a prepositional phrase. We can also turn to our best teachers, our favorite writers, and copy down sentences from their work that demonstrate a mastery of prepositional phrases. Then we imitate how our writers have used this technique and compare our efforts to the originals.

Is this kind of practice a lot of work? Yes, it sure is. But if you practice this way, with any writing technique, you will build your skills faster and more effectively than you can possibly imagine. And then, you will own those skills, you will be able to use them at will, and you will develop an unshakeable confidence in your ability to do whatever you want on the page.

I can speak from personal experience here. Some years ago, I taught myself all the techniques of diction and syntax I present in my latest book, Spellbinding Sentences. Even more important, all those months of practice, all that training, transformed me into a writer with skills she can depend on.

But don’t take my word for it. Get yourself a copy of Peak. Read it carefully and figure out how you can use the principles of expertise acquisition Ericsson describes. Then make practice an ongoing part of your writing routine. The  right kind of practice, Ericsson tells us (along with perseverance and ongoing effort), can change our brains. It can turn us into the writers we’ve always wanted to be. It might even change our lives.

right kind of practice, Ericsson tells us (along with perseverance and ongoing effort), can change our brains. It can turn us into the writers we’ve always wanted to be. It might even change our lives.

For more from Barbara Baig, check out Spellbinding Sentences: How to Achieve Excellence and Captivate Your Readers.

Barbara Baig is the author of Spellbinding Sentences: A Writer’s Guide to Achieving Excellence & Captivating Readers and How to Be a Writer: Building Your Creative Skills Through Practice and Play. She offers free writing lessons at WhereWritersLearn.com.

Thanks for this excellent review, Barbara. So interesting, succinct, and helpful.

You’re very welcome, Richard.

[…] view post at https://janefriedman.com/practice/ […]

I haven’t read “Peak” yet, but it sounds pretty interesting. What I would have said before reading the post (based on title alone) is “No, you will not get better by just writing.” I would have said that it requires also taking the time to read what you’ve written, and get feedback from others, and really analyze what you’ve done and what others say. All the critiques in the world will not help if you refuse to acknowledge the weaknesses and areas of improvement in your writing.

I will add that I have not considered practicing as laid out here, but I certainly will going forward. Thanks!

You’re absolutely right, jeffo. No one can improve who is convinced his or her writing needs no improvement!

Love this post! I bought Barbara’s book, “Spellbinding Sentences” and my 2016 new years resolution was to complete at least one of her writing exercises every day. Last month I brought a new draft to my writers group meeting and they were all blown away, they all noted how much my writing has improved. Thank you Jane and Barbara.

Thanks, Rachel. And good for you for making that New Year’s resolution and sticking to it. Your story shows what’s possible when we devote time and energy to improving our skills.

Aloha Barbara, so nice to hear from you! I can’t say enough good things about your book and I recommend it to all of my writer pals.

Thanks so much, Rachel. I do appreciate your recommendations.

[…] que te impiden escribir. Si te comprometes, serán indispensables la paciencia, la práctica (deliberada) y el esfuerzo, así como aceptar que se trata de un proceso de mejora sujeto a críticas, en el […]

I heard Ericsson interviewed on the radio and did not make the connection with writing and yet it is so obvious. Thanks for making the connections for me Barbara.

You’re very welcome, Kathryn. I hope you can now move on to discovering what Ericsson’s methods can do for you.

[…] If You Just Keep Writing, Will You Get Better? (Jane Friedman) How can this be? How can a training approach used by top golfers, divers, ballet dancers, surgeons, and many other people possibly help writers? The answer is simple: it’s all in our brains. When it comes to becoming better writers, most of us make three assumptions. […]

[…] to the rest at Jane Friedman and thanks to Matthew for the […]

[…] Source: If You Just Keep Writing, Will You Get Better? | Jane Friedman […]

[…] Jane Friedman […]