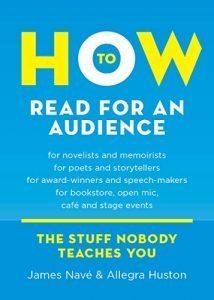

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from the writer’s guide book How to Read for an Audience: The Stuff Nobody Teaches You, co-authored by public speaking coach and creative mentor James Navé (@JamesNave) and author and workshop leader Allegra Huston (@allegrahuston).

When you’re nervous about reading in public, you tend to picture the audience as the enemy, distant and judgmental, just waiting for you to mess up. If you think about this for a moment, you’ll realize that it’s an illusion born of fear. In fact, your audience wants to love you and your work. Some of these people probably already do.

The audience is on your side. They love writing just as you do; that’s why they’re there. These wonderful people have taken time out of their lives, probably traveled some distance and spent some money, just to hear you read. They’ve come to witness your imagination at work. They’ve come to be moved, entertained, motivated, validated, informed, provoked, stimulated and inspired. In short, they’re receptive.

They are your allies.

So, what are you going to read? Here are things to keep in mind as you make your selection.

Crafting an emotional connection

The strongest impact you can make when reading aloud is emotional, not intellectual. For that reason, you will do best if you choose content you have a strong emotional connection with: passages that make you laugh or cry—if you let yourself.

- Pre-select more material than you will have time to read, with a wide emotional range. You’re not a robot. You’re not going to feel the same way every day, or want to read the same material.

- Make your final selection on the day of your reading. If you’re going through a difficult time in your personal life, you may want to present material that reflects your emotional state—though if you don’t trust yourself to keep control of your emotions, go with something safer. Include as wide a range of emotion as you can manage—or, if it’s a short reading, choose material that builds to a powerful climax. Either way, take your audience on a journey.

- If the event has a theme, take it into account. Even if you have to stretch to make a connection between the material you want to read and the theme, make sure you do. The organizers will not invite you back if you totally ignore the brief they gave you.

- If you are one of two or three readers at an event, you will probably have about 20 minutes (more on timing below). Unless you are an expert at this, DO NOT choose one continuous passage or one long poem. You will find it challenging to hold an authentic emotional connection for that long, and your audience’s attention is pretty much guaranteed to wander. Instead, choose poems of varying lengths or three- to six-minute passages from different parts of your book. For an event where you are the sole author reading, select five or six passages or 12-15 poems.

- Even though you have been asked to do a reading, it doesn’t mean that all you’re allowed to do is read. You may do better to structure your presentation as a talk about your work.

Timing your reading

After you’ve identified the passages or poems that you might include in your reading, or developed a talk about your writing, the next step is to get an accurate timing. This is where many rookie readers run into trouble. They don’t time their reading in advance, they time it inaccurately, or they decide it’s okay if they run over a bit. Almost always, it’s not okay.

Find out how much time you will have for your reading. Open mic slots run three to six minutes. Curated multi-writer readings allow 10-20 minutes. Solo events can run an hour or more: usually 30-40 minutes of reading followed by an interview and/or a Q&A.

Staying within your allotted time is one of most professional moves you can make. Less is more. If you have 5 minutes, prepare for 3 minutes. If you have 10 minutes, prepare for 8 minutes. If you have 20 minutes, prepare for 16 minutes. The extra time allows for introductory remarks, pauses, off-the-cuff comments, and audience response. If you finish under time, your audience will want more, your fellow readers will appreciate you, and your host will ask you to come back.

If you’ve ever been to an open mic, you’ve almost certainly seen a reader exceed the time limit. This is not only unfair to the other readers, especially those last on the list; it’s unfair to the audience. Some people have come specifically to hear those people who have just been elbowed off the program. Everyone has come to hear a variety of voices. Being greedy, even unintentionally, makes a reader unpopular all around.

We’ve often heard people say, “I only have five minutes. If I read fast, do you think I can get through all five pages?” Sure, it’s possible if you read like an auctioneer, but you’ll lose your audience. It’s always better to read less and read it well.

Time your pieces with the stopwatch on your phone. Begin by reading each piece aloud at what seems to be a normal speed. Chances are it will take longer than you expected. If that’s the case, trim your material rather than speeding up your pace. As you rehearse, your pace is likely to slow down even further, so cut your selections down far enough to give you room to expand.

Editing your material

Many writers don’t realize that they’re “allowed” to make changes to what’s on the page. You can leave out words, sentences, even paragraphs, if that serves the reading. The reading is its own thing: It’s not “a chunk of the book” or legally binding testimony of its contents. It’s an event, and your task is to engage your audience.

What should you leave out?

Wherever possible, omit phrases and sentences that refer to other characters or plot lines that will distract or confuse your audience. And leave out anything that starts to feel inauthentic or clumsy in rehearsal. It happens frequently that you’re happy with a passage when you read it over on the page (perhaps you’ve read it over a hundred times on the page), but when you read it aloud, putting full emotional weight into the words, you realize you’re not happy with it at all. If you’re uncomfortable with even one word, cut or replace it.

Parting advice

When you stand up in front of your audience, you’re making a bargain with them. In return for the effort they’ve made to be there, you will give them an experience of human connection, though the emotions you share may range from ecstasy to hilarity to rage. This sense of shared emotion is why we read. It reminds us that we are not alone, that life is infinitely sad and infinitely sublime, and that there is always something new to fascinate or appall or delight us.

For more insight on reading or performing your written work, check out How to Read for an Audience: The Stuff Nobody Teaches You by James Navé and Allegra Huston.

James Navé is a public speaking coach and writing mentor who has taught creative writing for institutions and schools worldwide. He co-founded Poetry Alive!, performers of classic poems for over 6 million students, and has produced creativity workshops with Julia Cameron. James directs the Taos Storytelling Festival and has written two books, The Road (1998) and Looking at Light (2012). He holds a poetry MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Visit his website.

Allegra Huston is the author of Love Child, Say My Name, and How to Work with a Writer. Editor at major London and New York publishers for 30 years and an editorial director for six, Allegra has run creative writing workshops for universities, conferences, and the UK’s Arvon Foundation. She has also worked with authors such as Sir James Goldsmith and Jane Goodall. Allegra’s English Language & Literature degree comes from Hertford College, Oxford. Visit her website.

This is just what I told my audience (the writers’ guild in my town) at our last meeting. My book-reading copy of Dakota Blues is a mess, with all the highlighting, post-it notes, dog ears, and penciled-in edits. It just gets better and better.

Something I’d add to this post: mix up the reading with the shmoozing from the podium. In between read excerpts, talk about the human stuff: why you chose the next passage, why it moves you, what happened when you were writing it. It’s human nature for the folks in the audience to want something they can take away, something that moves them, a bit of wisdom or humor or insight. It’s never 100% about the author or her works. You’re there to entertain, in whatever way is authentic to you.

Lynne, You’re spot on about schmoozing from the podium. Do you think it is fair to say schmoozing and storytelling go hand in hand? Allegra and I do spend time addressing the idea of schmoozing from the stage in our book. My 93-year-old mother passed away a little over a year ago. She and I were very close. I wrote some narrative verse about her passing. Last summer, I read the poems in at the SOMOS Literary Salon in Taos. Between each poem, I told little stories about the experience. After my reading, many people in the audience told me that they felt like my story was their story.

Lynne, I appreciate the “human stuff” suggestions to add so much more than a back cover bio and book description. I will share this personal slant of why I chose a passage, why it moves me, and what happened when I wrote it.

What a wonderful piece, reminding us that what we are after is the human, emotional connection that allows the listeners to be active participants. Musicians and actors say the same thing—that what they receive back from the audience, as they perform, is a vital part of the experience, adding meaning to what they are trying to offer. It stands to reason that oral reading from our books would be no different. I appreciated the practical advice too (e.g., about having the freedom to edit what one reads). A keeper!

Barbara, Thank you for comparing oral reading to music and acting. When I think of words spoken aloud, I think of Emily Dickinson little poem I’m Nobody. “I’m Nobody! Who are you? / Are you – Nobody – too?

Editing while you read is a bit like a jazz player adding notes when the emotional impulse feels right. Those notes float from somewhere like the memories from the old man’s imagination at the end of A Child’s Christmas in Wales. “I could see the lights in the windows of all the other houses on our hill and hear the music rising from them up the long, steady falling night.”

AND, if it’s an open mic, don’t be upset by the audience of poets desperate to get up and flog their 5 minutes. The quality of their attention will be strained, and you’ll feel it—that NEGATIVE wave of energy coming at you, saying “get the fuck off the stage so I CAN READ….!”

Jefferson, James Navé here. In my experience, many of the poets desperate for their five minutes of open mic fame tend to be less seasoned, or rank beginners. I still have some patience with them because I’ve seen more than one carry on like that for a while then somehow get over it and drop into a groove that works. Unlike the old dog in your poem going in, going out here’s hoping all poets have a chance to sing into their songs rather than flog their minutes.

[…] James Navé and Allegra Huston detail how to plan a book reading that will delight your audience. […]

[…] James Navé, Allegra Huston: How to Plan a Book Reading That Delights Your Audience […]

Great post! For the readings of my first novel, I asked thespian friends play the role of the characters. I played the narrator. Picture old time radio. No one was bored. For my 2nd novel, I plan to tape my friends and post the dialogue on the website.

[…] read more https://janefriedman.com/plan-book-reading/ […]

This is a wonderful, wonderful post. No frills, no clever build-up, nothing cutesy, just fantastic expert advise, point after point. Not only is this brilliantly useful, it’s great writing. Thank you both. (And I will totally check out the Taos Storytelling Festival.)

I think what I most got from this excerpt is the idea of real warmth between myself and the audience. I LOVE the instruction about emotion. It’s why I write, and what readers love, yet face to face I don’t believe they feel as much and me and the Grand Canyon do… I don’t play it safe in my books, but I have been on stage. I’ve gone for the laughs but never the tears. Your advice is so good. Makes me want to go weep with them, then laugh it away.

🙁 🙂