For 12 years, I worked at a mid-size commercial publisher, and on rare occasion, I would receive a frustratingly vague query from an unagented author. Such authors would promise to send more information after I signed their non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

I never agreed.

First, I couldn’t enter my employer into that kind of agreement without permission from the executive team. (And they would have laughed me out of their offices.) But perhaps more important, NDAs have never been part of the traditional book publishing business. When literary agents submit work, they don’t ask editors or publishers to sign NDAs. When literary agents agree to represent their clients, no one signs NDAs. Etc.

So when you encounter the NDA as an editor, agent, or publisher, you know you’re dealing with someone who isn’t familiar with the standards of the industry. Of course, it’s true that once you put an idea out into the world, there is the possibility someone else will steal that idea and use it for themselves. Ideas can’t be protected under copyright.

But in publishing, do you know how hard it is to profit from an idea alone? Almost impossible. You have to be able to execute it well. And execution is everything.

In any event, whether you agree or disagree with the above, the hard truth is that no literary agent or traditional publisher will sign your NDA before reading your proposal or manuscript. It’s hard enough already for the average writer to have their work read and considered. If you add the NDA into the mix, you might as well self-publish now.

Further reasons for not using NDAs

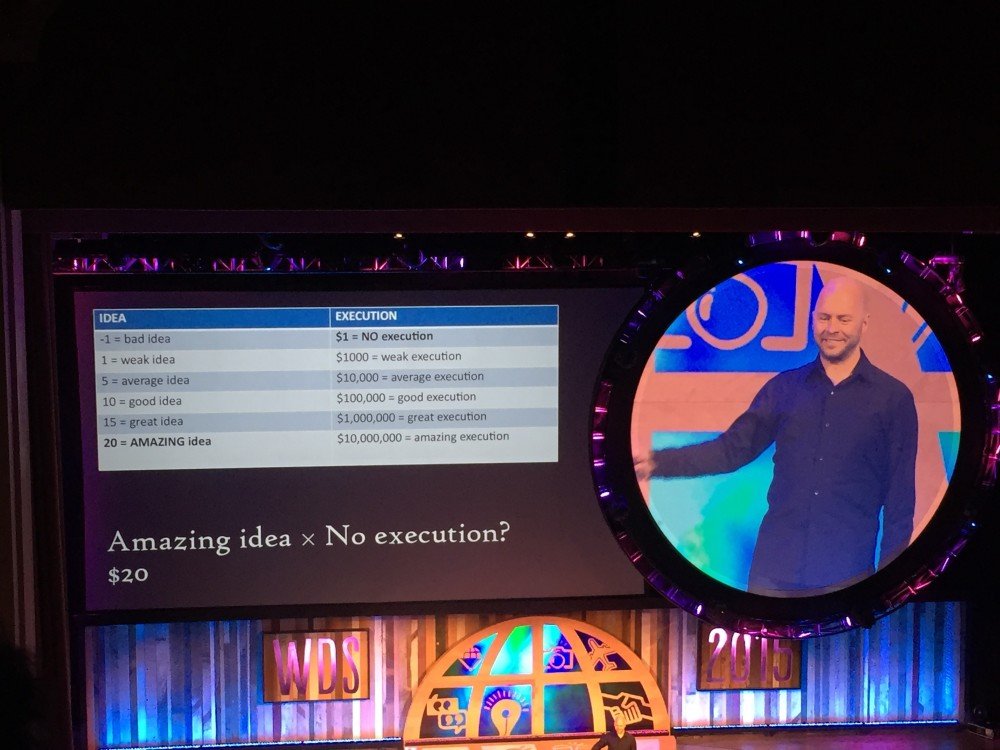

When I heard Derek Sivers give a talk, he showed the following slide.

Sivers also dislikes NDAs. He’s in the startup and tech industry, where they’re far more prevalent. But even in that more profitable industry, execution (again) is everything.

No one can execute your idea like you can. With fiction, no one can put your voice, style, or spin on the characters and plot. With nonfiction, it will require the right personality, brand, or platform to pull the idea off in a way that’s meaningful or profitable. (Not to mention the right marketing, packaging and distribution.)

And no one can be you. If anyone could be you, you’ve got a problem.

These days, perhaps because I’m a full-time entrepreneur, authors ask me to sign NDAs more frequently. I always say no, partly because of everything I’ve just described. But NDAs also indicate an author with a scarcity mindset, someone who is probably too invested in a single book idea. They may think: This is the only valuable idea I will ever have, or the most valuable idea I will ever have.

Anyone holding on that tightly to something can be a difficult person to work with. The level of sensitivity or emotional investment can be hard to navigate.

Furthermore, as a person working for herself—and without a legal team—I don’t want to expose myself to any potential legal quagmire, not unless it’s a very special scenario. Consider what this company says (I agree):

NDAs are serious legal documents. Our lawyer says it’s a bad idea to sign one before we know the party well and understand what we’re promising not to disclose. He’s particularly not fond of NDAs that are broad and general. We try to listen to him.

For more reading:

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

I totally agree. This comes from one of my books, not yet published:

“Don’t worry about people stealing your great idea.

If your idea has the potential to change the world,

you will be lucky to get just one person to listen to it.

To have a person steal it, this would be a miracle.”

— from “Life’s Secret Handbook”

[…] Asking an editor or agent to sign a non-disclosure agreement is not part of traditional publishing business practice—and it's usually a red flag. […]

This is fantastic. I’d like to add one thing that’s implicit in your post, but maybe not explicit. If you’re worried about someone stealing your actual words — not your idea, but the expression that makes it live — your work is protected by copyright. Your writing is protected by copyright the minute you write it on paper or save it on your hard drive. If an agent or publisher steals a writing sample or manuscript you’ve submitted, those actual words are protected without any need for a nondisclosure agreement.

If you’re worried about this, the best way to protect yourself is to keep a good record of what you’ve sent. If you want an extra layer of protection, it’s easy to register your copyright through the eCO (electronic copyright) system, at http://copyright.gov/eco/. Either of these is a heck of a lot cheaper than hiring a lawyer to draft a nondisclosure agreement!

And Jane is right: ideas without expression are a dime a dozen. It’s your unique treatment of those ideas that you want to protect.

Excellent points—thank you, Melynda!

[…] NDA) como este para proteger nuestra idea original antes de su publicación. Ahora bien, en realidad casi nadie los firma en el sector editorial; entre otros razonables motivos, porque no se puede […]

Jane, thank you for writing this. I totally agree. As an attorney, I am often asked about NDAs, and now I’ll send them to your post.

I try to explain to writers that agents and publishers are in the business of seeing new ideas and manuscripts. Their professional reputations are too important to tarnish by stealing someone’s work.

Really appreciate your POV here, Helen. I agree. Thank you!

Really great post! NDAs are very common in the PR industry and while our author don’t ask us to sign them, many of the publishers or PR companies we’re contracted with do. Some are more straightforward, while others I’ve refused to sign because they could leave us liable for too many things.

Very useful—thank you for letting us know the PR/publicity side of things!

Hi Jane. My husband is in the financial services industry and he’s fells the same way as you about NDA from folks who are SURE he should be selling their product. He says, “Thanks, but no thanks.”

[…] Agent Janet Reid discusses several business situations to avoid, while Jane Friedman points out why using non-disclosure agreements is a bad idea. […]

[…] between editor and author, and some editors have strong opinions about being asked to sign one. Writer’s Digest editor Jane Friedman gets a little incensed about them here. But in special circumstances, your lawyers or your agent or your publisher might feel more […]

Wondering if this is the case for protecting the identity of a human subject. I need an editor on an article for federal laws and authentication; the issue is allowing the final draft. The need is for an edit but to protect the subjects involved. Any ideas to not be a red flag, this an academic piece outside of University.

I’d discuss your concerns with potential editors when hiring them. There should be some kind of vetting process on both sides (I suggest you approach 2-4 to find the best fit). Let them know about your confidentiality issues and give them a chance to express how they’d handle it. Some may already have terms/conditions or a contract that says they will not share information about the project without explicit/written permission.