This post first went live in June 2016; I’ve updated it with more recent industry statistics. If you enjoy this post, I highly recommend subscribing to The Hot Sheet, an email newsletter for professional authors that I write and publish.

When I read mainstream outlets on publishing industry issues (such as The New York Times or The Guardian), few things are more frustrating than articles that tout the “resurgence” of print—as well as the related “comeback” of independent bookstores. Most of it is wishful thinking rather than an understanding of what’s actually happening. Here are the recent data points you should know about.

The ebook sales decline (to the extent it’s real) relates to traditional publishing and its high ebook pricing.

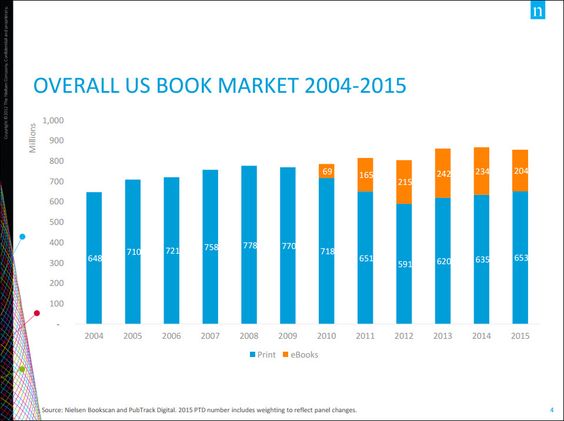

As you can tell from Nielsen’s graph above (which tracks sales of titles with ISBNs), the flattening of ebook sales started happening back in 2013. However, this decline is attributable to higher ebook prices from traditional publishers. Jonathan Stolper (formerly of Nielsen) said at Digital Book World in January 2017, “Price is the most important and most influential barrier to entry for ebook buyers and the increase in price coincided with the decrease in sales.”

If print is indeed is “back,” it’s because of Amazon. Since 2013, the traditional book publishing industry has enjoyed about a 3% increase in print book sales. However, print book sales grew largely because Amazon sold more print books. Barnes & Noble’s sales declined by 6% in 2016, and sales from mass merchandisers (Target, Walmart, etc.) also declined. But reports estimate that Amazon’s print sales in 2016 grew by 15%, primarily driven by their own discounting. (Their ebook sales are believed to have increased about 4%.)

When Amazon discounts the print edition, it often ends up undercutting the (high) ebook price. (It is not allowed to discount ebooks.) So it’s clear that consumers are unwilling to pay more, or about the same price, for an ebook as they do for print.

Two other unanswered questions:

- whether book readers are transitioning from ebook purchases to audiobook purchases; that’s where most of the sales gains are happening for traditional publishers.

- whether the most voracious ebook readers have switched to ebook subscription services such as Kindle Unlimited or Scribd.

Kindle Unlimited (KU), Amazon’s ebook subscription program, is estimated to represent about 14% of all ebook reads in the Amazon ecosystem. KU costs $9.99/month and is strongly dominated by self-published books—none of the major publishers participate.

Ebook market share has drifted toward “nontraditional” publishers.

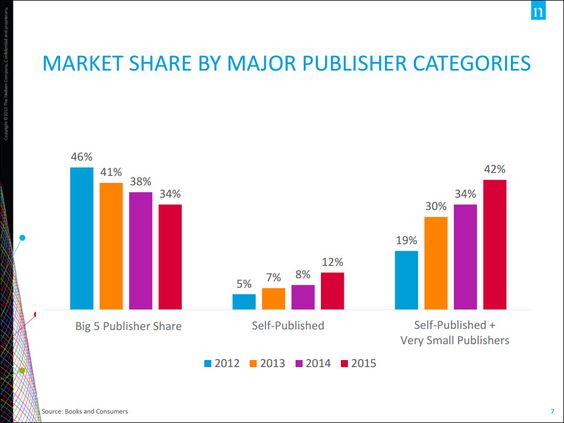

“Nontraditional publishing” includes self-published titles, small publishers, and Amazon imprints. Above, according to Nielsen, we see how the share of Big Five publishers has declined by 12% between 2012-2015; small publishers and self-published authors gained 23% market share combined, due to their lower pricing.

What’s even more astonishing about this graph is that Nielsen’s figures primarily give us a look at very traditional types of publishing, or books with ISBNs. There’s a whole universe of independent publishing that remains untracked because the titles don’t carry ISBNs—and most of those titles are not getting carried in your average bricks-and-mortar bookstore. They sell predominantly through Amazon.

Also, not many people are aware of what an active publisher Amazon itself is. Eight of the top 20 Kindle sellers in 2016 were from Amazon’s own publishing imprints, and Amazon now has 13 active imprints. In 2016 alone, Amazon Publishing released more than 2,000 titles.

Fiction sales are about 50% digital for traditional publishers

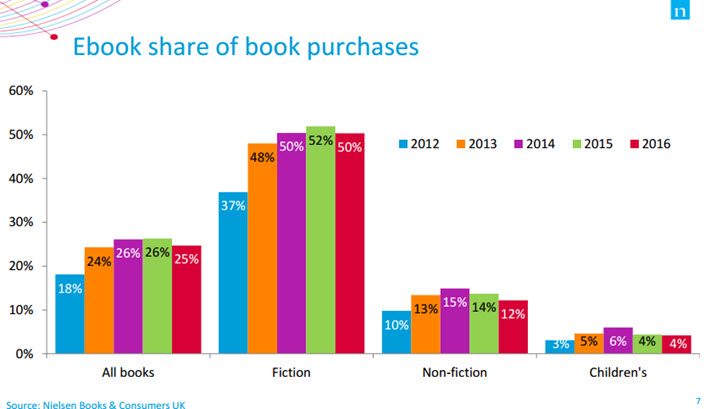

Often you’ll see figures that indicate that ebooks account for about 25% of all book sales for the major publishers, as in this recent graph from Nielsen, presented at London Book Fair in March 2017.

But note that’s an average across all genres and categories; if you look at fiction alone, sales are about half digital for traditionally published books. Once you factor in the nontraditional sales (self-published titles and Amazon Publishing titles), it would be within reason to expect about all fiction sales to be about 70% digital.

Barnes & Noble is losing market share to Amazon

Throughout 2016, the biggest bookstore chain in the United States struggled. During the holidays, the chain reported that comparable-store sales were down 9.1% versus 2015. The drop was attributed to various factors, including slower foot traffic in stores, the declining sales of adult coloring books, and no bestselling album by Adele.

The latest B&N quarterly earnings report showed a retail sales decline of 7.5%. Nook sales (which include devices, ebooks, and accessories) declined by 25.7%. B&N stated, “Despite post-holiday sales improvements, trends softened in late January and into the fourth quarter.”

Meanwhile, print book sales so far in 2017 show that the industry is not suffering that same rate of decline—so B&N is losing share to its competitors. The bookstore chain Indigo in Canada is showing growth, although that growth is from non-book merchandise. (Book sales remain flat at Indigo.)

Independent bookstores are doing OK, but just OK

Over the last few years, one of the feel-good publishing stories has been the rise of the independent bookstore. However, even though memberships at the American Bookseller Association (ABA) are up, stores still face issues of long-term sustainability.

For independent bookstores reporting to Nielsen, unit sales increases in 2016 were around 5%, compared to a 6.4% increase in all US print book sales. While independent bookstores have benefited from the “shop local” movement, better technology for store management and sales, and better terms from publishers, one has to be extremely optimistic to envision them growing in the face of a competitor like Amazon. (Amazon has been opening its own bricks-and-mortar bookstores across the country. They’re relatively small at 3,500 square feet; the average Barnes & Noble is ten times that size. All the books are face out, so the emphasis is on curation, and no prices are listed. Prices are variable and depend on whether the customer is an Amazon Prime member.)

At a recent conference, ABA CEO Oren Teicher said that the average profit margin of an independent bookstore is 2.4%. Therefore, even small changes in costs—such as wage or rent increases—can quickly make a store unprofitable.

To survive minimum wage increases, Shelf Awareness reported that booksellers seek to add products with a better profit margin than books: “Books Inc. [in San Francisco] has increased its sales mix from about 2 percent in gifts to around 15 percent currently. [They] would highly recommend that any bookstore not selling gifts do so.”

Additionally, booksellers are hoping for better terms from publishers, which isn’t necessarily wishful thinking; in 2016, HarperCollins launched the New Bookstore Development Program to support the opening of new independent bookstores or those expanding to new locations.

Bradley Graham, the co-owner of Politics & Prose, told Shelf Awareness that, despite the recent optimism surrounding indie bookstores, they still face serious challenges, and “the industry is not necessarily on firm financial footing for the foreseeable future.”

Carry a big dose of skepticism, and look at possible underlying agendas, when you hear celebrations about print’s comeback. While I’m not at proclaiming the death of print or traditional publishers, few media outlets have an understanding of the big picture.

If you’re interested in ongoing analysis and information about publishing industry, start a free 30-day trial to The Hot Sheet.

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

[…] view post at https://janefriedman.com/myth-print-coming-back-bookstores-rise/ […]

[…] Discussions about the "resurgence" of print and the comeback of independent bookstores amounts to wishful thinking, not an understanding of the industry. […]

The notion of resurgence is fueled by hopeful relief that for the moment printed literature will not disappear. A fear I have always taken as childishly declinist. All that should matter to dedicated readers and writers is the longevity (or to coin a phrase, the sustainability)of literature…

To that end I /we should rest assured that there will always be 400,000 serious readers in the world—a kind of cultural affirmation of the old saw, “The voice of reason is small but persistent.”

The apparent continued success of small independent presses is a very positive sign that even the book business is viable below the level of printing conglomerates , whose constituencies are far greater than just readers…

Thanks for doing the research on this, Jane. It makes a lot of sense.

In my own experience as a successful indie, the subscription Kindle Unlimited service is now 60% of my income. And my ebooks don’t have ISBNs because they don’t need them. The reason they can say ebooks are dead is because few successful indie authors (who price their books fairly compared to legacy publishing and are therefore selling quite well by comparison) are going to use ISBNs for an ebook. Bowker charges unfair prices for ISBNs. If indies pooled our resources and bought big blocks like legacy publishing can (at pennies per ISBN instead of $30 to $100 dollars each depending on how many one buys) that could change but that’s unlikely to happen. The ISBN system is broken. We need a new system to measure sales. Period. It’s a barrier to being COUNTED. Why would an indie invest in this when the vendors don’t require it? It’s just another way for trad pub to obfuscate what is actually happening in publishing and its no secret Bowker is part of that dinosaur system. In some countries ISBNs are free. Consider that.

Wow! I didn’t know ISBN’s were so expensive! I am ‘traditionally” published so never had to deal with that, but want to indie pub my next book. I would certainly hesitate before spending that.

I’m fortunate. When I got into publishing in 1999, I picked up 1,000 ISBNs from Bowker for $600 or 60 cents each. Even then the pricing was weird. Buying 100 cost $400 and I knew that I’d use more than that, so I opted for 1000. Ten times as many for only 50% more. I will never use that 1,000. But having them when each new books consumes about five is reassuring.

The current mess has a reason. ISBNs exist as barcodes for printed books much like the barcodes on soup cans. There was no reason to keep that system for ebooks. A much more rationale system could have replaced it, one where the barcode itself could have portions that would define the content, the version, the formating, and any DRM. Authors and publishers would only need to buy and register the publisher/content portion. They could assign the latter numbers themselves. Readers would benefit too. The content and version number would tell them they were getting the same ebook, with only the format differing. That’d have been a much better scheme.

It is the major publishers who drove the industry to stick with ISBNs even for digital versions. My hunch is that covertly Bowker made them an offer. It would grossly overprice small quantities of ISBNs to burden independent authors and small publishers, while still selling ISBNs cheaply in bulk to large publishers. Faced with a rapidly changing market, large publishers weren’t trying to win any niceness prize.

That’s backfired. The result has been that many ebooks are no longer tied to ISBNs, with Amazon not insisting on them and Smashwords offering its own set of ISBNs for authors to meet the demands of those on its distribution chain, such as Apple and B&N, who insist on ISBNs. Rather than stengthen ISBN, the scheme weakened it.

There’s a hitch, however, to your scheme to have authors bulk-buy ISBNs through some entity. An ISBN is tied to a publisher. That’s not just in the U.S. That’s global. The 58742 part of my ISBNs is my Inkling Books. The only way authors could bulk buy ISBNs is if they formed a publisher-like entity that bought them and tied those books to that publisher. That’s what Smashwords does. As a distributor, it plays quasi-publisher. But I’m not sure just doling out ISBNs to authors who handle their own distribution would work. Someone, for instance, has to go into that Bowker account and put the book’s information into Bowker’s database.

In short, it’s messy because a 1970s-era business model—print barcodes and traditional publishers—is still being imposed on a market that’s going in other directions. The problem is compounded by the fact that Bowker holds a stranglehold on U.S. ISBNs and demands such a high toll. In a book market as large as the U.S., Bowker desperately needs competition.

Interesting article but I think you miss the point that ebook sales are rising by all indicators outside of the Nielsen ratings – the majority of ebooks don’t have ISBNs and therefore don’t get counted.

I didn’t state that point directly, but under #1, I discuss that the ebook decline that’s oft-discussed in the media is related to traditional publishing’s numbers, not indie publishing, and under #3, I mention the ISBN issue and lack of good stats on the overall market.

Author Earnings is the only indicator I’m aware of that speaks specifically to any kind of increase in ebook sales outside traditional channels. Can you link us to any other data sets, indicators, or official reports about increasing ebook sales within the last 1-2 years?

Thanks for the reply, Jane. I would refer you to Author Earnings which is the only data source that is reliable for ebook sales, since Nielsen primarily looks at ebooks published by the major publishers and discounts or ignores indie publishers. ( http://authorearnings.com ) Their site uses a search algorithm, rewritten each quarter, to scrape earnings and sales stats from Amazon (since they don’t report that themselves). Their reports are very complete and the raw data is open source so anyone can analyze it. The latest report (May 2016) pulls in an estimated 90% of all ebooks sold on Amazon including the major publishers, small publishers, and indies in their stats. This is a more reliable data set from which to pull information on overall ebook sales in my opinion.

I’m aware of Author Earnings and heard “Data Guy” speak at Digital Book World earlier this year. His is just one method of analysis and it has to be considered alongside official, point-of-sale reports. I know Author Earnings is popular among indie authors, but each method of analysis out there prioritizes one type of sale or publisher over another (or has an agenda), so again—a complete picture is hard to come by if you only look at one set of data.

Amazon has reported increased ebook sales through official releases. For their sales to be up, while the Big 5 are seeing decreased sales, means growth is happening somewhere.

Thanks, Hugh. Can you provide links to those releases?

http://www.wsj.com/articles/e-book-sales-weaken-amid-higher-prices-1441307826

The relevant quote:

“Amazon says e-book sales in its Kindle store—which encompasses a host of titles that aren’t published by the five major houses—are up in 2015 in both units and revenue.”

Thank you! I wonder how much Amazon gained as a result of Nook’s declining sales. Michael Cader of Publishers Lunch calculated in March 2016 that Nook’s digital content sales have fallen by 56 percent since 2012.

That’s quite a surprise–a bout the 12 million coloring books. It’s too bad there isn’t better tracking of self-published books. It seems that the data would be valuable to so many in the industry.

Interesting, but my illustrated nonfiction books on Canadian history, traditionally pubbed, are going against the trend here. My e-book sales are 30% higher than my print sales.

Fascinating to learn – especially since conventional wisdom says that illustrated books do even worse in digital form than fiction/narratives.

Very helpful discussion. However, there is a common misinterpretation of the second chart. The text says “the share of Big Five publishers has declined by 12% over the last three years.” That’s incorrect. It has declined by 12 “percentage points.” The actual decline is 26%–1minus 34/46. That’s more than a quarter! Similarly, while self-published and very small publishers have gained 23 “percentage points” in market share, they have actually gained an astonishing 220%! You’ll see this easily if you note that 42% is more than twice 19%. Journalists get tripped up by these statistical issues all the time, but in this case they have a dramatic impact on the story you’re telling.

There’s a reason my degree is in writing and not math. (haha) But it does make sense that the smaller the base you start from, the more exponential the percentage increases will be.

Oh, wow. Excellent point Vicki Weisfeld. And quite important. Something to keep in mind for all of us. It’s not just journalists who get tripped up.

I climbed the mountain of statistics understanding in college, so want to get the most for my effort! 🙂

It’s a pedantic point, but that increase from 19% to 42% represents a multiple of 2.2x times but “only” an increase of 120%. To convert an increase from a multiple to a a percent, subtract 1x, so a 2.2x increase is plus 120% (i.e., 2.2 less 1). Use a simple example: if sales grow from 2 to 4, they’ve doubled (2x) while growing 100%.

In a declining market, even 120% increases in market share may be misleading. The best numbers to look at are sales figures as authors eat dollars and not percentages. (I’m not suggesting that is the case here, just making a general comment.)

Cogent analysis. Coloring books are skewing print, for sure. Also, a fact few people mention: a coloring book gets used up. More or less one-time use. Not good for libraries but great for the consumer market.

Great reminder about libraries!