My publishing career started at an undergraduate literary journal, The Evansville Review. When I became editor in 1996, it was the first paid editing job I held.

In no small part due to my fond memories of that time, and my belief in the power of literary journals, I gave up a tenure-track university job to work for one, the Virginia Quarterly Review—which I had read and admired from afar after Ted Genoways transformed it into a cutting-edge, award-winning publication.

I’m no longer at VQR, but the literary publishing community remains important to me, even if it is something of a love-hate relationship. (Literary types remain far too obsessed with and focused on the print artifact, as well as too quick to separate art and business—or believe they must be antithetical to one another.)

Earlier this week, Michael Nye of The Missouri Review published a piece at their site, Stubbornly Submitting to a Literary Magazine Is Good. He writes about a staff discussion, where one editor explained to an intern why they wanted writers to keep submitting after getting rejected multiple times:

… [G]etting rejected by a magazine repeatedly and then, finally, getting work accepted is, actually, fairly normal. It’s a little frustrating for an editor, she said, when a writer submits to us five times and then just stops and we never get the chance to read the writer’s work again. To emphasis this point, she noted that TMR has published several writers who sent manuscripts to us for over a decade before we published their work.

I posted a link to this piece (and quoted it) at my Facebook page, and I did not expect the conversation that ensued. Some comments were positive, but the majority were negative.

“Well, I got tired of banging my head against the same walls in a system that wasn’t working great for me.”

“If you reject my work for years without serious encouragement and some fine tuned explanation of why, there are other fish in the sea.”

“I don’t really understand how his example is relevant or encouraging. It seems more like a what not to do to me, rather than a what to do.”

“Stories moldering in an endless submission queue do no one any good, including the author.”

“I still think I might better spend the next ten years beating water with a stick—at least at the end of that time I’d have toned arms, instead of a publication in a magazine no one is ever going to read.”

“Well, note to editors of Missouri Review: This writer’s going indie!”

“Screw that.”

In the comment thread, I betrayed my bias toward traditional publishing when I mentioned that I found the piece encouraging rather than discouraging. Aren’t we all preaching how writers need to be persistent? That they need to let rejection roll off their backs?

But clearly this wasn’t the only takeaway for the community of writers—some professional and accomplished—that I reach via Facebook. (I should add here that more than 80 people liked the post and 13 shared it at last count, so it’s getting positive attention, too.)

In defense of literary journals, they can only publish a handful of pieces in the span of a year, out of thousands and thousands of submissions. They often operate on a shoestring, are in danger of losing what little funds they have, and mostly spend their time trying to stay afloat and carry out vital functions (like publishing a magazine).

Also, the kind of work that literary journals publish is largely noncommercial—e.g., short fiction, poetry, personal essays. Such work can have little importance or value when it’s published outside of the recognized literary ecosystem. (This is not a value judgment, but an observation.) Anyone submitting to a literary journal who doesn’t understand this from the outset is ignorant of the game that’s being played. While it’s possible to build your reputation through self-publishing, either in print or digital, the literary community highly values editorial selection and “standards,” not self-publishing.

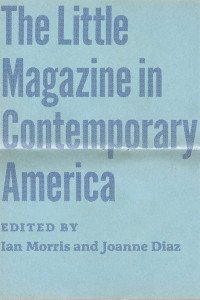

I titled this post “Are Literary Journals in Trouble?” because I would never have been able to fathom the response I saw to Nye’s post even five years ago—even though I’ve written essays about this exact problem! I’ll quote from my most recent piece (published in this anthology):

If a publication only reaches a few thousand people at best, then its influence and prestige must far outpace its actual reach to matter to writers and the broader culture. Even if very few read the publication, and it is a failure in commercial respects, people need to have heard of it and equate its name to respectability and exclusivity.

That game is starting to fall apart because, in the digital age, literary journals premised on great literature must now play the exclusivity game even harder, to the point of absurdity, and manufacture what is ultimately a false scarcity. The number of places and opportunities to get published has never been greater; the cost of distributing and publishing work is falling to zero; most writers can get read more widely by publishing themselves online than in print. Literary journals, even if they don’t acknowledge it themselves, are often protected far more by legacy and long-standing reputation than by somehow producing the ‘best quality’ literature.

I go on to discuss that literary journals have done little to move beyond their gatekeeping function. Instead of clinging to the scarcity model, they should create more opportunities for publication and engagement, with themselves as the leaders and moderators in the community. When the number of visits to a publication’s submission guidelines page is greater than that of any of its content—but there’s no interaction with those writers, and in fact writers are simply asked to pony up for a subscription—that sets up a dynamic in which the people who should value you come to either hate you or ignore you. And that is exactly what is happening.

Unfortunately, given how some journals can barely keep up with basic operations, I’m not sure how many will be able to experiment with alternative roles, responsibilities, or publishing models.

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

I read Michael’s piece the other day and found it so encouraging. And then, when reading the negative comments, a sense of bewilderment. I don’t think anyone is particularly happy with the state of publishing but really, so many of the comments just sounded bratty. I wanna make money as a writer ad well, rather than spending it. I’m broke, sick and in despair. But do I understand why my novella subscription to Griffith Review costs 50 bucks? Yes, because the judges are writers too and like to be paid. That theyre way less broke than me and I need that money for iHerb is something I can’t afford to think too hard on. No one’s forcing me to do this.

I was conflicted about the responses as well. Anyone submitting to literary journals as a way to build a paying or sustainable writing career has misplaced expectations. On the other hand, the gatekeeper position is becoming less valuable and/or respected for some writers.

We are witness of a (r)evolution in the publishing industry triggered by Amazon and the like. Jeff Bezos has opened the gates and the gatekeepers are looking at each other unsure of what to do.

Self-publishing has created a marvelous thing: everyone can publish a book, and establish a one-to-many direct relationship with readers who buy and enjoy the new voices.

There’s a terrible monster that haunts the publishing valleys, too: everyone can publish a book, and readers are exposed to the slush pile for the first time visible to the many.

Recently, Books-A-Million has declared that its bookstores will be equipped each with POD printers. “Every book is printed because it has been sold,” breaking the old paradigm stating that “every printed book maybe is sold.”

The advent of cheaper and cheaper flash printers, together with higher and higher print quality, makes so that printing books in advance hoping to sell them later is bound to disappear as a business model.

Books are already in online catalogues available to all bookstores. These last will have their own POD printers in the back office, and customer will access loads of online information about the authors and their listed works. A reader will be able to pay and download to a device with RFID (a short distance wi-fi service, think of bluetooth), and/or click to buy the printed edition. Get a coffee or a latte at the embedded BookStop Café and be served latte, cake, AND a freshly baked book, right on the spot.

No more distribution costs, no more returns. Every single printed book is printed because it has been bought. Bookstores will have a never ending catalogue and be able to sell any physical book.

Dinosaurs that will disappear are those publishers who still believe that their service and added value to writers is primarily to get published, and writers need to put up with everything else for that privilege. This business model is no more sustainable because the basis for it is no more. It will disappear, and those who don’t change business plans will be soon forgotten and crumble faster than IBM did when the clone PC and the primitive Windows operating system made through to the market.

I also see the end of the query process. Agents will perform like professional sport scouts. They will look proactively for writers online; after all, a promising athlete doesn’t go to every scout’s house and run 40 yds dashes in his front yard hoping the scout’s lurking. The athletes play their game, and the writers will write their novels. In both cases, the audience is there already, scout or no scout, agent or no agent, and for a writer that is all that counts.

I’m sure many aspects of your vision will come to pass. What I’m not so sure about: (1) That physical inventory will ever go away. I have to assume there will always be economies of scale for books that sell in the thousands or millions of copies. Also, people love the bookstore browsing experience too much—that aspect of discovery seems likely to continue even if it has to be subsidized by the publishers. (2) On the other extreme, is print-POD the best way to offer frictionless delivery? Digital seems the more obvious path for easy, cheap, and quick access to books.

For (1), I didn’t mean the inventory proper to each bookstore, a few copies for patrons to browse titles on demand, but the need to keep tens of copies of the same book stocked away in the cellar and waiting to be returned will fade away. I agree that with books that sell millions of copies a bookstore owner will prefer to keep a good inventory at hand but the vision of a future with a fast, good quality POD machine in the bookstore itself will make copies made-on-the-go much cheaper and convenient for the bookstore than ordering a pallet of books from a distributor across the country (and store them away.)

The big POD like Createspace (Amazon) and IngramSpark solve only one part of the equation (reduce the number of returns) but the delivery part remains. Digital is indeed the obvious path to distribute a book, and for those who like the physical touch, a small POD printer in the bookstore will deliver a warmly printed book in just two minutes wait, as soon as the ready-to-print file is received 🙂

Besides, this would make for any book available in a digital format to be sold also as a printed edition through any bookstore at any moment. Quite nice, I’d say.

[…] Literary journals have done little to move beyond their gatekeeping function, and cling to a scarcity model that no longer works in the digital age. […]

Interesting post, Jane.

I’ll admit that litmags are the #1 reason I went indie. Sometimes rejection has nothing to do with your story at all. Even professionals and bestsellers still get rejected. Sometimes a story just isn’t the right fit for a magazine. Nothing you can do–just write the next story and move on.

Writers should be writing more stories, faster. It’s the best way to improve your craft as a writer, not slowing down and waiting for a magazine to accept you. A magazine might never even acknowledge you. Then what?

But I also think that magazines don’t do enough to add value. For example, as a reader, it frustrates me to no end that I can’t buy most of the major magazines on my Kindle. There’s no excuse for it. As an author, there’s no incentive for me to submit to a magazine that can’t adapt to the times, especially if they don’t pay. I also wish that magazines featured fewer authors. Hard for readers to notice you when your work is mixed in with dozens of other writers every month. By the time they read your story, there’s another issue, so they forget about you.

Hopefully mags will adjust, or hopefully we will see new mags rise to prominence who can operate in this new world and make money at it.

Spot on. Your comment makes me sad at where we’ve ended up. Hopeful for evolution, but how many will survive it …

I concur. They put themselves in a corner from where it is difficult to escape.

I completely agree with Michael. I do most of my reading on my Kobo – major magazines included. Writing and publishing are changing fast but not so fast that these litmags should not have caught on by now.

I find the entire process a little frustrating. In a very quickly changing world to arrogantly hang on to old processes and antiquated ideas doesn’t seem to be productive OR encouraging for any of us. I believe we can all survive it but we will have to embrace the change and come up with our own “angle”. I am involved with a group who wants to encourage entrants in a writing contest to print their submissions, put them in an envelope and mail them to a post office box. POSTAL SERVICE – has any one read the news lately. Why on earth is that necessary with drop boxes and all types of different methods of communication today. I have an idea why but we need to get over it and embrace the change.

Even Darwin talked about it. “It is not the strongest or the most intelligent who will survive but those who can best manage change”

I wonder if some publications prefer paper submissions if only because it creates friction. The era of Submittable has allowed writers to send their work out in much higher volumes than ever before.

Not condoning (there are other solutions!)—just suggesting one reason why this method could be seen as preferable for journals.

First, lets look at the literary magazine and its focus. It really is a wing of academia. It socioeconomic background of those that run it, I dare say, would be very similar. They don’t make money because for the most part, the people that work for them don’t need the income. And who reads them, or at least gets a copy?

But the role of the journal was to engage a wider audience to writing of value. Unfortunately, it is rather insular. It is really just producing and validating the writing of a small in group. I think this is just like the situation when Dana Gioia asked if poetry mattered–and that was ten years ago. If literary magazines have no real vitality within our culture and are just pitching to a narrow group, is “saving” them worth it?

It should be pointed out that the literary journal was the only way for this type of work to get out. But if I can simply run a literary blog, of my own work or work of others, why bother with the journals? Even my blog (not literary, but not exactly showing high-traffic content), can get more eye-balls in a month than what the print run of some of these journals are (and if you factor out the copies that automatically go to a library that are never read either, I am doing a lot better).

So for the creative person, what is the point of doing work? To have it in a particular journal or to be read? (We will leave economics aside, but no one earns a living through publishing in literary journals.) In academia, it does matter where you are published, by does a reader care? Unless you have an academic career (academia is really very extremely conservative in this regard), why would you? Now, forging your own path is not easy. You need to do what literary journals for the most part don’t do anyway, which is to find and connect with a readership. There is the responsibility of claiming your work. You need to know how to edit or get someone that can and a whole host of skills, but getting published the traditional way is not easy and requires many of the same things.

I think we are going through a great change in publishing, and I mean this broadly, not just in regards to books and journals. Perhaps the role of the journal, at least in this form, has run its course. Every time I hear pleas that we “need” to save book stores, or journals, or whatever the failing institution a small groups cares about, I ask why the suppliers for those institutions are called upon when they obviously cannot support themselves and are becoming marginalized. Should I ask what has replaced them and look to see what is going to support my work? How much of an opportunity does a writer lose if literary journals go bust? I am not sure there is a good answer to that for the journals.

Now, with this great opportunity to publish, there are diminishing returns for income. But like I said, literary journals are not exactly a great avenue for income either.

Can’t say it better than you have, William. Thank you.

“First, lets look at the literary magazine and its focus. It really is a wing of academia. It socioeconomic background of those that run it, I dare say, would be very similar. They don’t make money because for the most part, the people that work for them don’t need the income.”

Wait…. what? People in academia don’t need income? What century do you think this is? In my experience, the people running literary journals are likely to have a second job in order to fund the publication. You know, on top of their work in academia, which pays them poverty wages.

http://www.nbcnews.com/feature/in-plain-sight/poverty-u-many-adjunct-professors-food-stamps-n336596

Moco, I just want to note that the article only deals with the plight of the part time college instructor, not the entire faculty. Many, if not most, college journals are handled by full time tenured professors who make an excellent salary.

Lora: you seem to think that

1) the tenured professors do most of the work,

and

2) they fund college journals out of their own pockets.

Both of these assumptions are flat-out wrong.

Also, there are so many journals that have absolutely no college affiliation. The bigger (“bigger”) ones are run as non-profits. Have you tried paying Brooklyn rent while you’re working at a non-profit? I haven’t either, but I can’t imagine it’s easy.

(The smaller ones are run by people who are working three or four jobs to finance their art and pay off their student loans. Barista/yoga instructor/adjunct/dog walker/poets. Who then sit down in the wee hours of the night and read submissions and manage their journals social media presence and fix the webpage when it breaks and meanwhile there’s a baby crying somewhere in the building and that couple’s fighting or fucking they can’t tell which and they have three hours before they have to get out of the apartment and help open the store at Starbucks.)

And even the most venerable college journals run into financial trouble. Have you looked at the publication history of the Kenyon Review?

When I was working at VQR, I had a real “duh” moment when I realized how much of the motivation that drove writers to submit or publish with us was tenure related, or otherwise connected to improving their academic position. So there’s “payment,” but not necessarily in cold, hard cash.

I think William’s reference to Gioia’s essay is appropriate, since it explores what’s been happening for many years now: poets (and others) writing and publishing within a confined and insular community.

I wonder if online literary magazines will have more pull in the future than print only ones. Brevity and Hippocampus both have active online communities and don’t have a print version. Writers might prefer to be published in a way that makes their work visible to a wider group of readers and more easily shared. River Teeth and Creative Nonfiction are print based, but they share smaller pieces online frequently to keep their audiences engaged. Creative Nonfiction also has active engagement by its readers/contributors on social media. In creating these online communities they provide a meeting place for writers to share ideas in addition to reading and submitting. The magazines I mentioned are all creative nonfiction–perhaps being a newer genre and newer publications has lead them to embrace changes in publishing more readily.

I think you’re right—and isn’t it interesting to see the CNF genre lead the way here? That never occurred to me, fascinating.

There are many dynamics at play here. One is the mechanisms to reach readers underwent fundamental shifts. The money that gets paid to writers has also gone through a fundamental shift. My lowly imprint gets paid by Amazon, Audible and LightningSource directly. Traditional publishers now have to compete for writers and they are doing a terrible job at it.

But,as Michael La Ronn and Charlotte touch upon, it’s the readers that have gone through the biggest shift. It’s not that it is inconvenient to leave the Amazon ecosystem (and it is), it’s that there is so, so much good stuff on Amazon that why would I bother leaving it in the first place? The moment, the actual moment I finish a great book or short or what have you, Amazon is right there, on my Kindle, recommending several works like it. And some of them are so good they make your heart ache.

The sad thing was not that Michael Nye’s article was a dip into arrogant (and it was arrogant). It’s that at no time does he talk about readers. The problem on the table is not a problem. Any exclusive club will have a line of unwashed masses wanting to get inside. And this blog entry’s premise that artificial exclusivity is detrimental to a publication’s health is spot on, although in this case apathy may be a better term than hate.

When you’re a publication and your problem is readers and your understanding of your audience, well, we all know what’s going to happen next, don’t we?

Well put, and apathy does seem the more appropriate, accurate term.

Just one other thought. Some literary journals require a fee from the author to be published–a very academic notion. You should not be paying a publisher for the honor of them using your work. In fact, a large number of academic journals are actually for-profit funded by the author. It is a great business model because you don’t actually have to sell to a readership. In the sciences, you also sign over all copyrights to the publisher. What other business get to charge their suppliers for their product, takes all rights for future sales, and then get to bill the academic library system on top of that. And when a lot of scientific research is publicly funded, who can loose?

Ah, yes. The way I define literary journals (or at least the way I draw lines around the community) would be to exclude those that require fees or take copyright. Those to me are the hallmark of scholarly/academic presses rather than literary ones.

Thank you Jane. You made my day with this thought-provoking piece.

I spent most of the 80’s and half of the 90’s in the literary cult or clique – even Allen Ginsberg basically called it that in an issue of Partisan Review. Looking back, I realize our snobbery, my friends and I who spent our money on books of stamps and half our time submitting to what we called the “prestigious” litmags. You know the ones well.

Back then, anything akin to “vanity” publishing was anathema, i.e. those anthologies and such that published anybody and everybody and had no standards. But it was like hitting the jackpot to be published in, say, Ploughshares or Paris Review. It was about building a reputable writer’s resume, nothing more. We used to always joke about not being able to cash contributors’ copies at the bank.

Thank you again, dear Jane, for speaking out on this mostly neglected subject. The times they ARE a changin’ – and thank God for it.