In a recent article at the New York Times, you’ll find a big-picture overview of what’s happening to US book sales as a result of the pandemic. Despite print sales being up around 8 percent overall—a record-breaking year—the NYT article paints a doom-and-gloom scenario, with considerable nail biting about the “profound impact on literary culture.”

Why so glum? Well, like other retail sectors, book sales have shifted online during the pandemic, which tends to favor older (backlist) titles and known favorites. Plus, some indie bookstores aren’t doing all that well with the transition to online sales.

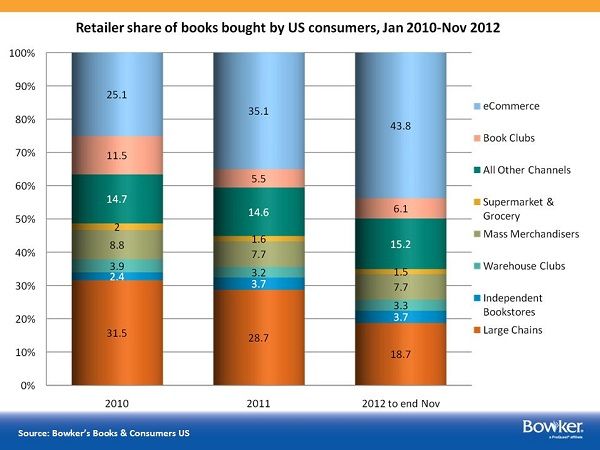

Unfortunately, the New York Times frequently gets stuck on independent bookstores as the way for new talent and new titles to get discovered, even though they represent maybe 4-5 percent (optimistically) of overall book sales in the US. The chart below, from 2012, shows them at 3.7 percent after the Borders bankruptcy. Further, the New York Times tends to interview and quote people who dislike Amazon and are Very Concerned About Literary Culture.

According to a Publishers Weekly ongoing survey of bookstore owners across the country, some independent bookstores have been managing well during the pandemic, with one store reporting 50 percent more sales than in 2019. To be sure, not all stores are thriving, and a few have experienced serious declines—but in the end, declines have been less drastic than predicted. All stores saw a shift to online ordering and have had to meet the challenge of fulfilling such orders. According to US government estimates, bookstore sales were down by 30 percent in 2020 through the month of November.

What you won’t find the New York Times discussing: the fortunes of self-published authors (many of whom reported growing sales during the pandemic), or much critical exploration of why some new titles didn’t do so well in the US when others did perform well in the UK. The Bookseller reported (subscription required) in January 2021 that debut novelists performed better in 2020 than in 2019, by a whopping 151 percent! (There’s one very famous author in there with a debut, but even without his help, debuts did fine.)

I’ve been reporting on how the pandemic has shifted and shaped book sales over the past year, relying on reports from Bookscan, Nielsen (UK), the Association of American Publishers, Ingram, and Publishers Lunch—plus I attended countless online industry events. Here’s the context and meaning that you won’t find in the New York Times piece.

Yes, more book sales are happening online

More people are shopping online than ever before due to the pandemic, and consumer behavior hasn’t shown any sign of reverting to pre-pandemic routines. During two recent webinars hosted by Ingram Content (the largest US book distributor), marketing experts described a dramatic change in the consumer environment. The US has experienced 10 years of ecommerce growth in three months, with books, music, and video seeing some of the most dramatic shifts to online sales. This new environment makes it critical that publishers and authors adjust marketing and sales strategies and build new skill sets, as these changes are likely to become permanent. (Nielsen UK, too, is seeing “stickiness” in the consumer transition to online retailers.)

While Amazon is still the largest online retailer for books, they have in fact lost a small amount of market share in the US. Target and Walmart have performed well, and they even took away a small percentage of Amazon’s share in book sales (about 2.5 percent), according to Jess Johns, consumer insights manager at Ingram Content. This may come as a surprise, given the large increase in revenues that Amazon has reported, and it’s true that the pandemic has been very good to them. However, Peter McCarthy, director of consumer insights at Ingram Content, pointed out that the online retail marketplace has become more diverse during the pandemic, not less. People are willing to shop at many different types of stores; they pay attention to business and brand values as well as to the impact of their buying decisions on the community. Furthermore, consumers know they have power and are using it. “What we stand for as companies matters more to consumers than ever before,” McCarthy said; bookstores, publishers and authors are not exempt from that.

The shift to online sales has benefitted all publishers

Full-year financial reports from 2020 are now available from the Big Five publishers with the exception of Macmillan, which is privately held. A quick summary:

- Penguin Random House increased sales by 4.6 percent and profits by 23.3 percent.

- HarperCollins increased sales by 7.9 percent and profits by 33.2 percent.

- Simon & Schuster increased sales by 10.7 percent and profits by 11 percent.

- Hachette increased sales by 3.9 percent. Its parent company, Lagardère, saw sales decline by .4 percent and profits increase by 11.8 percent.

- In the UK, print sales grew by about 5 percent.

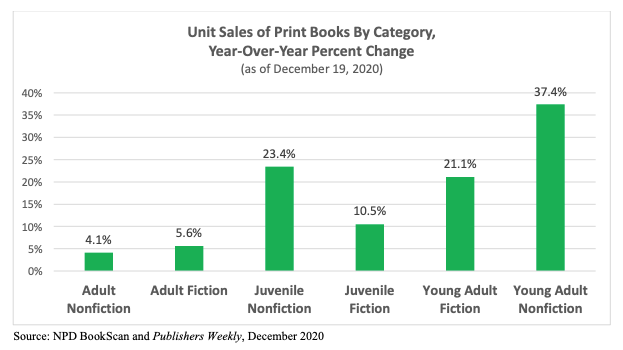

Michael Cader of Publishers Lunch has noted (subscription required) that children’s books account for a significant chunk of sales growth. He also credits publishers’ good performance to lower returns—20 percent lower than in 2019—which helps not only sales but profits. There are also increased ebook and digital audiobook sales for just about everyone.

Cader also recently pointed out that large publishers have been slowly losing market share due to the shift to online sales, which favors other publishers and self-published authors. He writes, “BookScan’s basket of ‘other publishers’ outside of the top 15 companies has been rising steadily year over year for some time now and would comprise their largest segment by far if you included the distribution clients who sell through Ingram Publisher Services, Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, and others.”

Learn more about those smaller, independent publishers across the country that have performed better in 2020 than 2019.

What about Barnes & Noble?

In a recent conversation at IBPA Publishing University, Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt spoke about the effect of the pandemic on the chain’s performance and how its strategy is changing to give local booksellers more power over what they stock and merchandise. But what caught our attention is Daunt’s comment that the shift to online sales for Barnes & Noble has been “relatively minor.” Given how much e-commerce has grown in the last year (and Ingram’s many webinars pointing out that these behavior changes are here to stay), this seems worrisome, but apparently not for Daunt. “I don’t think the book you get in your mailbox delivers the same pleasure as the book you selected by interacting with a knowledgeable bookseller,” he said. Read more in Publishers Weekly.

The shift to online sales favors backlist titles

People today discover books through varied platforms and channels—retailers, libraries, social media, and subscription services—and that variety favors backlist sales. Backlist titles are older titles (usually more than one year old); their share of overall book sales in the US increased to 67 percent in 2020 from 63 percent in 2019. McCarthy said, “Online, things flatten out a lot” because there are no front-of-store displays, no face-out promotions, no end caps, and so on, which tend to feature new titles. Publishers and authors need to smartly respond by paying attention to a broader set of titles in their marketing, not just frontlist. McCarthy advised marketing relevant backlist alongside new releases. “An older book a consumer hasn’t seen is new to them, and that’s evident in the [sales] numbers.”

Recent research by Rachel Noorda and Kathi Berens at Portland State shows that the number-one way people discover books is word of mouth—that is, a recommendation by a friend. The second method? Whether the book is by a favorite author, reinforcing the truism that a strong author brand is vital. But an equally important message from their research is that—despite these top two methods of discovering books—book discovery today is incredibly varied and involves different media, such as video games, TV, and movies, especially for Millennials.

It’s not all about the independent bookstore recommendation, and publishers who still rely on that set of influencers absolutely must rethink their approach.

Audio sales and subscription services continue to grow

All formats have seen sales growth during the pandemic; readers like different formats and tend to read multiple formats. During the pandemic in particular, Ingram saw increased interest in subscription models and libraries, but those options did not have a negative impact on print sales, according to Johns. Rather, Ingram sees an increase in readership, which is increasing sales, not cannibalizing sales.

Digital subscription service Storytel recently released its 2020 annual report, showing that it exceeded its 2020 revenue goals, although the company is not yet profitable as a whole, only in specific markets. As of January 2021, it reported 1.5 million subscribers to its unlimited subscription model, which pays out to publishers and authors based on time consumption. It anticipates growing subscribership to 2.1 to 2.2 million people by the end of this year.

Kindle Unlimited also continues to grow—or so it’s assumed, given that payouts to indie authors continue to grow and Amazon doesn’t release any other figures that can be compared over time. Ebook distributor PublishDrive reported that it saw sales through subscription services double in 2020.

There’s also increased dealmaking during the pandemic

Deal volume, which increased in 2020, continues to grow in 2021, according to reports at Publishers Marketplace, which has been tracking deals for more than 20 years. Total deals are up 19 percent over 2020, with gains across all categories. Nonfiction has seen jumps in memoir, religion/spirituality, and business; in fiction, debuts and women’s fiction/romance are doing well. Read more from Michael Cader (subscription required). See the comments of this post for additional detail.

How long can strong sales last?

In 2021 so far, print unit sales are up about 30 percent versus last year, according to NPD BookScan.

Three consultants have written a free report on COVID’s anticipated impact on traditional and higher ed book publishing and related sectors in 2021. They anticipate consumer price sensitivity in the market, high demand for library ebook lending, continued analog-to-digital evolution, and a need for publishers to revisit and strengthen direct-to-consumer marketing.

The report concludes that “the seismic change is in digital,” and that “from now on publishers must treat bookselling as digital-first, physical-second, with no further questions asked.”

If you enjoyed this post, take a look at my paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet, which offers business intelligence for professional authors.

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

That’s interesting that deals are up. I feel like every writing group I’m in is full of people talking about how slow editors are to read and offer this past year. Any insight into whether that uptick in deals is mostly established authors selling more books vs. debuts?

In addition to deals being up, submissions are also way up. Some agents are reporting double the volume right now. A publisher in France actually pleaded with writers to stop sending in their manuscripts for a while. Longer response times are likely a result of increased submission volume and the problems of the pandemic (e.g., working from home, children at home).

Publishers Marketplace reports that, in fiction, debut deal announcements have been rising steadily year-over-year. In the first quarter of 2020, 82 debut deals were reported. In the first quarter of 2019, that number was 76. In 2021, it was 91.

Excellent behind-the-scenes overview (and snooping), Jane.

And the “shift to backlist” is indeed a good thing for Indie author/publishers like myself. For me, it’s really ALL about growing a backlist for the rest of my life (gulp). Title by title, the backlist grows, and remains on-sale for the next 500 years ;-))

And finally, “digital-first, physical-second” is exactly what I’m seeing in a ratio of 10:1 in my book sales.

Informative, as always.

Great insight…even if it does make me a little nervous about trying to argue that I should get to keep playing after a tough debut year!

[…] Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth A. Harris take a look at how the pandemic has shifted publishing, and Jane Friedman adds deeper context about how the pandemic is affecting book publishing. […]

Excellent article. The majority of indie bookshop owners I’ve interviewed over the past seven months have all said while the transition to online selling took an adjustment, they expect online sales to stay stronger than their pre-pandemic online sales when they fully reopen.

Once customers realized that in order for their communities to be there post-pandemic, they needed to support local businesses and keep the tax dollars in their communities.

Many indie bookshops would not have survived without the support of the ABA. Over 700 indie bookshops took part in indie bookshop day this year – that’s a huge increase over 2020. And many had record sales which is wonderful.

I’m constantly surprised with the unique ideas indie booksellers come up with to keep their relationships with customers afloat, even when they can’t see them in person. Out of chaos comes creativity!