Today’s guest post is adapted from My Creative Space: How to Design Your Home to Stimulate Ideas and Spark Innovation, 48 Science-based Techniques by author and architect Donald M. Rattner (@donaldrattner). Illustrations are courtesy of the designers and author.

As an architect and the author of a book about the psychology of creative space, I have long wondered why contemporary creatives cluster so willingly in noisy coffee shops. Granted, there’s scientific research that caffeine fuels the imagination, but doesn’t the surrounding din interfere with their ability to think creatively such that no amount of chemical stimulation can compensate for the distraction?

Certainly, many eminent writers from the past shunned clamor. Consider Marcel Proust. To remark that the French writer was sensitive to auditory interference would be an understatement. The man was positively neurotic about it. He treated the bedroom in his Paris apartment where he wrote like a sensory deprivation chamber—shutters closed, drapes drawn, the walls lined with sound-absorbing cork. It wasn’t enough. He wore earplugs too.

Anton Chekhov was similarly beset by hypersensitivity to sound. So was fellow obsessive Frank Kafka, who described his condition in his signature surreal style by saying that “I need solitude for my writing; not ‘like a hermit’—that wouldn’t be enough—but like a dead man.” Sadly, by the time he got his wish, it was too late to do anything about it.

The correlation between high-level inventiveness and difficulty in filtering out sensory inputs is understandable, given that open-mindedness is a hallmark of the creative personality. The problem for off-the-chart geniuses like Proust, Chekhov, and Kafka was that their minds were a bit too open. Everything got through. Hence the extreme measures they took to avoid being immobilized by incoming stimuli.

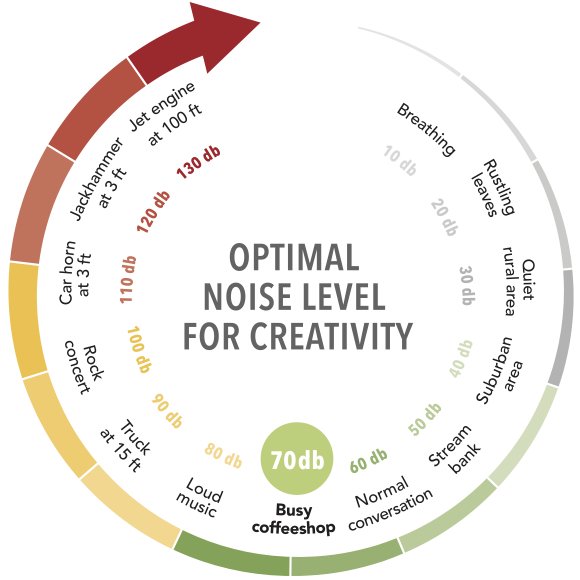

Then again, most of us aren’t Marcel Proust. According to research data from 2012, most people reach peak performance under moderately noisy conditions—70dB (decibels), to be precise. It just so happens that this is roughly equivalent to the chatter in a typical coffee shop or restaurant on a relatively busy day (Fig. 1). It also approximates the crash of ocean waves breaking on the shore, the study thrum of crickets, and wind rustling tree leaves.

As to why this is the case, the scientists who authored the study offer a theory:

We theorize that a moderate (vs. low) level of ambient noise is likely to induce processing disfluency or processing difficulty, which activates abstract cognition and consequently enhances creative performance. A high level of noise, however, reduces the extent of information processing, thus impairing creativity.

Translation: silence isn’t as golden as it sounds. Absolute noiselessness tends to focus our attention, which is helpful for tasks that entail accuracy, fine detail, and linear reasoning, such as balancing our checkbook or fixing a Swiss watch. It’s less supportive of the broad, big-picture, abstract mind-wandering that leads to fresh perspectives and a creative work product. On the other hand, excessive noise overwhelms our sensory apparatus and hinders our ability to properly process information at all. In between lies the sweet spot—noise not so loud that we can’t hear ourselves think, and not so quiet that we can’t help but hear ourselves think.

There’s a caveat to the data, however: the noise has to be white. For the record, the technical definition of white noise is noise containing multiple frequencies with equal intensities. More colloquially, the phrase refers to a constant background noise, especially one that drowns out other sounds, and which takes the form of meaningless or distracting commotion, hubbub, or chatter.

Why is it important that the noise be white? Because otherwise you’re prone to tune into and attempt to discern the source and meaning of the sound, which diverts too much of your conscious attention from your task to be a useful tool for diffuse thinking.

How to Make Noise When There Isn’t Any

How can we creative mortals who don’t care for the smell of coffee, lack the funds to construct an oceanside villa, or live in urban environments where trees are scant benefit from the finding that a particular type and level of noise can promote insights? Here are a few options to consider:

Get the app. Yes, Virginia, there really is an app for everything. Use the search term “noise” to bring up dozens of sound generating programs in your smartphone’s app store. You’ll also see a broad selection of metering apps for measuring decibel levels at home.

Some of the app companies operate websites that let you download audio files of white noise soundtracks onto your computer or play them directly through a browser. A couple of my favorite sites include Raining.fm, which offers tracks simulating—what else?—downpours, rolling thunder, and heavy thunderstorms, and Coffitivy, which specializes in—what else?—coffee shop buzz.

Get or hack a sound generator. Another option is to purchase a desktop appliance designed to emit white noise. They’re smallish devices, typically placed on night tables and in babies’ rooms to help occupants fall asleep. For an architectural solution, think about installing an indoor or outdoor fountain—few things in life are as pleasantly hypnotizing as the mellifluous whoosh of water descending onto water. Price points run the gamut from low cost store-bought products to sky’s-the-limit custom installations.

DIY contrivances also abound; consult the Internet for guidance.

Let in or keep out external noise. City dwellers and people who reside along busy highways might have a ready-made noise machine right outside their window: road traffic. Open your windows to varying degrees or use sound muffling, such as drapery, to see if you can calibrate ambient noise to fall within the optimal range.

A less cacophonous strategy for harnessing exterior sounds would be to park yourself on a bench or beach that lies within earshot of ocean waves. It’s like having an always-on fountain, only bigger.

A less cacophonous strategy for harnessing exterior sounds would be to park yourself on a bench or beach that lies within earshot of ocean waves. It’s like having an always-on fountain, only bigger.

Listen to music. Like noise, music can have a positive effect on idea formation, while affording the listener far greater pleasure than the usual restaurant ruckus. But music is a huge subject in itself, and so must wait for another day!

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this post, check out My Creative Space: How to Design Your Home to Stimulate Ideas and Spark Innovation, 48 Science-based Techniques by Donald M. Rattner.

Architect Donald M. Rattner helps individuals and organizations maximize their creativity by drawing on scientific research into the psychology of space. Educator and author as well as practitioner, Rattner’s publications include My Creative Space: How to Design Your Home to Stimulate Ideas and Spark Innovation, entries in professional reference books, and numerous contributions to print and online channels. He has taught at the University of Illinois, New York Academy of Art, New York University, and Parsons School of Design. Workshop and lecture venues include Creative Problem Solving Institute, Creative Mornings, and many others. His work has been featured on CNN and in such publications as The New York Times, Work Design Magazine, L-Magazine, and Better Humans. Podcast interviews can be found on Creativity Quest, Love Your Work, The Creative Life, and Killer Innovations, among others. He holds a Bachelor’s in art history from Columbia and a Masters of Architecture from Princeton. More at donaldrattner.com.

I prefer a very quiet space for writing and definitely do not use music while I write. The problem is we live in a noisy world and I have found that most people are noise-obsessed (having their phones on loud, obnoxious rings and dings, the annoying sounds of computer gaming noises, etc.). My apartment is reasonably quiet but you can’t help but hear some degree of traffic noise. Nevertheless, you have to write where you can, when you can so I have to try my best to tune all the racket out.

Lining the walls with cork. Hmm……

I like a bit of sound when working at home on projects (editing, writing) and have bookmarked some youtube videos, such as a soothing several-hours-long “spa music” track that I play at a soft volume. There are dozens out there, depends on what works for my mood.

The author fails to comment on a reason why some of us cannot tolerate noise: Auditory Processing Disorder. Background noise of various types make it so we can’t understand what others are saying and often can’t process thoughts ourselves. I suspect his examples from the past may have suffered from this condition to some degree. Sometimes it’s biology, not personal choice.

What a fascinating article! I prefer silence when I write, but I noted recently that I came up with a lot of ideas when I had some soft music playing. Makes me wonder if there aren’t different optimal noise levels for the different phases of writing. Music for brainstorming, white noise for the first draft, total silence for revising.

I think I’ll experiment with some of this and see what happens. Thanks!

I’m a classically trained musician and cannot use music to write by. My mind tunes in every time and tries to dissect the piece I’m listening to. It’s also difficult for me to sit in public and write because, without fail, the “white noise” is interrupted by the occasional louder noise: a baby crying, the drop of a glass or a tray, etc. Sudden loud noises startle me out of any focus I managed to achieve beforehand.

Instead, I go to YouTube and find a long video of rain falling, without thunder. That works fairly well for me.

I never imagined I had something in common with Proust and Kafka! I need total silence to write, and for me white noise is just … noise.

I keep the TV on in the other room, so I have the voices and minimal music. Having AADD, I use it because a) silence drives me batty and b) I ‘concentrate against’ it. As to music – no way can I have that going, at any level. I find myself humming along, singing along, tapping my fingers – it invades my brain! It’s the same reason when at my day job I can’t have music like so many of my cohorts. I get into the rhythm of the music which clashes with the rhythm of the task.

[…] Creativity is where writing starts. Beth van der Pol tells us creativity is making mistakes, and Dawn Field says creative leaps are the lifeblood of great writing, while Donald M. Rattner argues that silence might not be golden for writers. […]

[…] Posted on October 28, 2019 by Donald M. Rattner | 5 Comments […]

Delighted to learn about this book; I’ve just ordered it. About noise– right now I’m listening to Radio Swiss Classic. Courtesy of Swiss taxpayers, this is an endless stream of delightful classic music. You can listen in here: http://www.radioswissclassic.ch/en

I find it good for doing email– which is what I was doing– I just surfed on in here from Jane Friedman’s emailed newsletter.

I’m on the Kafka end of the continue–no silence is too deep to keep me happy when I’m writing. But then, my first profession was as a musician, and tuning out sound takes enormous effort for me. I can ignore all the shiny objects you dangle, but an odd smell or a random sounds…. hopeless. The idea that ANYBODY can write something meaningful in a coffee shop utterly bumfuzzles me, and yet, 90 percent of my writin’ buddies consider four hours on a hard chair a ‘Bucks to be their best session so of the week. Go fig.