Note from Jane: Last week, I ran a comprehensive guest post on how to find the right critique group. To help add to the nuance and complexity of that issue, I’m happy to feature the following guest post by Jennie Nash (@jennienash), the Chief Creative Officer of Author Accelerator.

Writers love the idea of writing groups. Writing is, after all, a very lonely pursuit. You sit alone in a room wrestling your ideas onto the page, struggling to fend off the constant attacks of doubt. Your regular friends probably don’t quite get what you are doing and can’t help. So it makes perfect sense to join other writers who can help you navigate the joys and sorrows of the creative process.

Unfortunately, the reality of writing groups is far more complicated than that. Underneath the good intentions there are serious dangers lurking.

In my work as a book coach I often see the damage that writing groups do, and it is not benign. Writing groups can cause fatal frustration, deep self-doubt, and sometimes years of wasted effort. In this post I’m going to outline the most common dangers of writing groups, and will also propose some ways you could improve your group to give you more of what you need—and less of what you don’t.

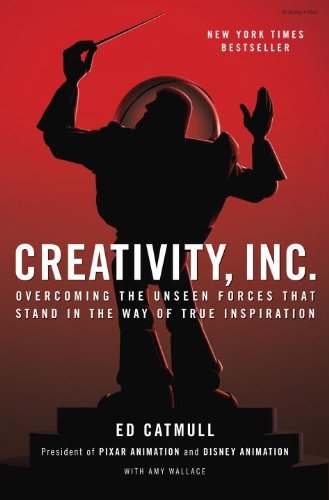

To illustrate my points, I’m turning to wisdom shared in Creativity, Inc by Ed Catmull, President of Pixar and Disney Animation. In this book, Catmull shows the many ways that the powerhouse studio has managed creativity, and in the process produced some of the most resonant and beloved stories of our time. He talks about the concept of management on a really big scale—department hierarchies and multi-million dollar movie projects—but the fact of the matter is that we all must manage our own creativity if we are going to do any good work, and his wisdom applies to all of us.

To illustrate my points, I’m turning to wisdom shared in Creativity, Inc by Ed Catmull, President of Pixar and Disney Animation. In this book, Catmull shows the many ways that the powerhouse studio has managed creativity, and in the process produced some of the most resonant and beloved stories of our time. He talks about the concept of management on a really big scale—department hierarchies and multi-million dollar movie projects—but the fact of the matter is that we all must manage our own creativity if we are going to do any good work, and his wisdom applies to all of us.

1. No one tells the truth and no one really wants to hear it.

Most writing groups tiptoe around glaring weaknesses in the work being shared and sometimes tell outright lies about it, because they don’t want to hurt people’s feelings. All the writer hears is praise or vague criticism that isn’t very actionable, and so they assume that what they are writing is solid (if not awesome) and they plow on creating fundamentally flawed work.

Praise is wonderful—it feels good to hear it—but it is not very helpful for the writer committed to writing a book that engages the reader. Writers must find a way to welcome criticism, even harsh criticism, but writer’s groups tend not to foster this skill, and as a result, no one grows, no one learns, and people become deluded about their work—believing it to be better than it is.

At Pixar, truth-telling is a central part of the creative process. As Catmull writes:

In the very early days of Pixar, John, Andrew, Pete, Lee, and Joe made a promise to one another. No matter what happened, they would always tell each other the truth. They did this because they recognized how important and rare candid feedback is and how, without it, our films would suffer. Then and now, the term we use to describe this kind of constructive criticism is “good notes.”

Before we get to the good notes part, let’s look at the promise to tell the truth. That’s the critical thing a good writers group needs—not an implicit promise, but an actual commitment. Every single member of your group needs to understand the promise about telling the truth, believe in it, commit to it, and welcome it when it is their turn in the hot seat. This starts with a shift in mindset, which Catmull describes beautifully:

Naturally, every director would prefer to be told that his film is a masterpiece. But, because of the way [our group] is structured, the pain of being told that flaws are apparent or revisions are needed is minimized. Rarely does a director get defensive, because no one is pulling rank or telling the filmmaker what to do. The film itself—not the filmmaker—is under the microscope. This principle eludes most people, but it is crucial: You are not your idea, and if you identify too closely with your idea, you will take offense when they are challenged. To set up a healthy feedback system, you must remove power dynamics from the equation—you must enable yourself, in other words, to focus on the problem, not the person.

Try the following fixes for your writing group:

- Every writer in your group needs to agree to speak the truth and to accept the truth. It helps enormously if the writers in the group have a similar level of expertise and experience, and if they share the same clearly stated goals. Someone writing a book because it’s cathartic and fun is in a very different place from someone writing a book for publication, and it could be that you need to shake up the composition of the group in order to be able to make a commitment to the truth. Making these changes can be heartbreaking—but that’s part of truth telling, too.

- Each member needs to speak with deep kindness and a sense of hope when it’s their turn to offer a critique. Mean-spirited attacks that leave you gasping for breath and feeling small are among the most damaging realities of all. There is a difference between telling the truth and being mean. Don’t allow mean.

- Each member needs to take a deep breath and welcome the truth when it’s their turn to hear it. Remember that when someone is criticizing your work, they are not criticizing you.

- Finally, the group needs to make a commitment to understanding what giving good notes is all about. Which brings us to No. 2 below.

2. Struggling writers are not often the best judges of struggling writing.

At Pixar, giving good notes happens in a meeting of what’s known as the Braintrust. “The Braintrust,” Catmull writes, “is made up of people with a deep understanding of storytelling and, usually, people who have been through the process themselves.” This is a critical concept that most writing groups don’t adhere to, because they can’t adhere to it. They’re often comprised of writers who are struggling to find their way for the first time, and it’s one of the main dangers of being in a writing group.

There is not one single thing wrong with struggle. Struggle is part of the creative process for everyone at every level, but why would you think that being in a room with other people who are also struggling with the same things you are, and who have no experience with that struggle, would be a good way to nurture your work? Yes, you might get camaraderie and community, which is nice, but by design, the odds of getting specific, focused, useful help with your story are low. Why is that? As Catmull writes:

While problems in a film are fairly easy to identify, the sources of those problems are often extraordinarily difficult to assess. … Think of it like a patient complaining of a knee pain that stems from his fallen arches. If you operate on the knee, it wouldn’t just fail to alleviate the pain, it could compound it. To alleviate the pain, you have to find and deal with the root of the problem.

A group of writers who are not trained to assess problems with a story or argument often get it wrong, or get it partially right, or demand specific remedies—not necessarily on purpose, but by a sort of unconscious group-think approach of what they like or don’t like. It’s not good. It comes without any assistance in how to move forward. You get the “it’s not working” feedback, but not the nurturing and patience you need to fix your problem, and certainly not the editorial understanding you need to prevent it from happening again. People may offer ideas for how they would fix things, or how they see your story or what they would do, but this is a sure path for crushing fragile new projects and wavering confidence.

So what exactly IS a good note? Here is the principle as Catmull describes it on his website:

Truly candid feedback is the only way to ensure excellence. When giving notes, be sure to include:

What is Wrong

What is Missing

What Isn’t Clear

What Doesn’t Make Sense

A good note is specific. A good note does not make demands. Most of all, a good note inspires.

Copy that principle down and laminate it so you can look at it during your writing group critiques. It is so smart. It’s not about praise of any kind whatsoever (although Catmull does say that most Braintrust meetings start with the members praising the director.) And it is not about ways the writer should fix the problem. It’s about identifying weakness in a very specific way, articulating them, and helping the writer to see them, and to sort out how to go about fixing them.

Try the following fixes for your writing group:

- Use Catmull’s criteria for giving good notes—and I mean literally. Make each note follow his format, and don’t allow any other commentary. That means never saying, “Ohh, what if your character is from another planet instead?” or “I think you should start at Chapter 5,” or “You’re the best writer, I’m so jealous, I wish I could write like you.”

- Hone your story analysis skills by learning the craft of self-editing—I highly recommend The Artful Edit by Susan Bell (principles of editing), Handling the Truth by Beth Kephart (the critical importance of truth in memoir) and Wired for Story by Lisa Cron (how to write fiction designed to give the reader what the brain craves.) Read these books in your writing group and discuss them and evaluate your own work according to their principles. This will be a powerful learning tool. You may also like my guide, How to Edit A Complete Manuscript. It teaches you how to put down your writer’s hat and put on an editing hat.

3. Struggling writers are not often the best judges of struggling writing, Part 2.

This point is so important that I’m making it again, in a different way.

Let’s assume that neither you nor your writing group members can hone their story analysis skills overnight. This is, in fact, often the reality. Many writers think they understand story and narrative because they love to read, and they are great readers, and they recognize a great story when it’s on the page. But that is very different from knowing how a dramatic narrative (for fiction) or a narrative argument (for non fiction) is constructed, or knowing how to get the emotion on the page, or knowing how to hold the readers’ expectation in your mind as you write. These are very different skills. Some writers are native geniuses at it, but those people are very rare. Most writers are honing their story analysis and narrative design skills in terms of their own writing, not in terms of being able to articulate it to other writers.

So how can you help each other with your work? If the people in your group don’t have the knowledge and expertise to diagnose problems, don’t do it. Seriously. Don’t. Consider skipping the editorial analysis completely and make the group be about accountability, camaraderie, support, and information-sharing instead of about the words on the page.

Try the following fixes for your writing group:

- Give each writer time to talk about the weaknesses they see in their work and the solutions they are contemplating. Let them try to sort those things out in a supportive space. Often, simply having to articulate your problem goes a long way towards solving it. I find that writers frequently know what’s wrong with their own work if you give them the time and space to confront those truths, and this is far better than asking people who are not trained to weigh in on what’s wrong with the work.

- Give everyone half an hour to talk about the problems they are having making time to write—or the doubt they are feeling about the point of their story, or their lack of faith in their worthiness as a writer. These are experiences every human is indeed an expert on (managing time, facing doubt, being brave) and experiences that can be fundamental to writing success.

- Assign members research projects. Spend time sharing what you have read about changes in the industry, trends in pricing, what readers are doing and saying and thinking, and how writers are reaching readers. Look at newsletters such as The Hot Sheet about the business of writing, or at Shelf Awareness, about the business of bookselling. Identify useful writing blogs (Save the Cat, Shawn Coyne) and push yourself to include sites that focus on social media and entrepreneurial skills (Alexis Grant, Joanna Penn, and Dan Blank). All of this is just as important to being a successful writer than the words on the page. I do not believe that excellent writing can come from writers whose only goal is to sell, but I also believe that writers who ignore the realities of how books are bought and sold, and ignore the demands of their readers and their competitors, are writing with their heads in the sand. Publishing success is often deemed to be mostly a matter of luck and timing—and while luck and timing certainly play a role, knowledge about the demands of readers and the realities of publishing is almost always a factor, as well.

- Save up your pennies to find an actual expert to help you with the words on the page. This could be an online group workshop from somewhere like Gotham Writers Workshop, UCLA Extension Writer’s Program or Writer’s Digest; a class at a nearby college; or hiring an editor or book coach. (Jane has a fabulous list of resources on her site here.)

4. Failure is not an option in a writer’s group, but failure is a part of the writing process.

Writing is a creative undertaking, and all creative undertakings are messy. Things sometimes get worse before they get better. Things can take a long time to come into focus, as you ping back and forth between what you thought you were doing and what you are actually doing, between the start of the story and the finish, between one narrative thread and another. Failure is part of the territory—a big part of it. Writing groups, however, tend to exclusively celebrate forward progress, and clean, linear thinking.

This happens because writing groups focus on only on one tiny slice of work at a time. If that slice happens to be logical, chronological, clear and well written, you get a thumbs up. Problems related to how that slice fits into the whole sweep of the story, or how it supports the premise, or how it aligns with the overall structure are largely ignored—and yet many of the most common problems I see are the result of flaws in these areas. When seen through a micro lens, a chapter can be beautiful and moving and polished yet be an utter failure at doing what it needs to do on a macro level—which is to drive the story or the argument forward towards a clear and resonant resolution.

Some of the best passages in Catmull’s book chronicle the early, messy stages of beloved stories like Toy Story. Can you imagine Woody ever being a character who was fuzzy and unformed? He was, and as you can imagine, that impacted every element of the story. The writers and producers wrestled with his character for a long time before hitting on the slightly neurotic little toy cowboy who adores his owner Andy and is nervous about the newcomer, Buzz. Catmull’s point in letting us inside Woody’s transformation is to show us that the creative process is never linear and straightforward, and that you must make room for failure:

Pixar films are not good at first, and our job is to make them so—to go, as I say, “from suck to not-suck.” This idea—that all movies we now think of as brilliant were, at one time, terrible—is a hard concept for many to grasp. … Creativity has to start somewhere, and we are true believers in the power of bracing, candid feedback and the iterative process—reworking, reworking, and reworking again, until a flawed story finds its throughline or a hollow character finds its soul.

Try the following fixes for your writing group—which are all reiterations of the points we’ve outlined, above.

- Tell the truth. If someone is not working—if it has a fatal flaw, if it’s ill conceived, if it has an underlying problem of logic—say so, in as specific way as possible. Don’t hold back for the sake of being nice. Nice is saving a writer from years of writing in the wrong direction.

- Be open to criticism. If you get deep criticism on something you have written, consider that you might need to scratch it, start again, go back to Go. Allow that reality a place at the table. Many writers say that they know something is working when they start throwing out a lot of pages. They can see their vision clearly—and they can see what doesn’t fit.

- Give good notes—and ask for them. Encourage the members of your group to ask for the help they think they need. Rather than reading a passage of text and waiting for generic feedback, urge the writer to say, “I’m having trouble with the passage where I explain my system for writing a resume. I’d like you guys to listen to see what I am missing.” This is, in effect, asking for a “good note.”

- Talk about the failure. Talk about the doubt and the agony of it all. Let the pain be part of the mix, because creating something out of nothing is not easy. It’s highly emotional work, no matter what the genre. Writers need support—real support, not just surface level support—and they need a place where they can fail. Let your writing group be that place, and you will be providing an invaluable service.

Jennie Nash is the founder and CEO of Author Accelerator, a company that trains, certifies, and supports book coaches so they can help writers do their best work. Jennie’s own clients have landed top agents, six-figure book deals, and spots on the New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller lists. She is the author of 12 books in 3 genres, including Blueprint for a Book: Build Your Novel from the Inside Out and Blueprint for a Nonfiction Book: Plan and Pitch Your Idea. Visit her at authoraccelerator.com and jennienash.com.

[…] Writing groups can cause fatal frustration, deep self-doubt, and sometimes years of wasted effort. Learn the most common dangers of writing groups, and find out how to improve your group to give yo… […]

I belong to an online critique group on Facebook. The comments on excerpts I have posted are great. I’ve learned so much about grammar, staying in pov, and punctuation, it’s scary. Sure, you need to develop lizard skin, but it’s worth it. What I have learned, I’ve been busy appplying to what I’ve already written. Thanks you Writers World and Randall Andrews for all the help you have given me.

Anna, I’m so glad you’ve found a group that’s helpful. That’s great!

[…] Writing groups can cause fatal frustration, deep self-doubt, and sometimes years of wasted effort. Learn the most common dangers of writing groups, and find out how to improve your group to give yo… […]

How to Edit a complete manuscript was one of the most lucid ( and practical) guides on the subject I have read ( and I have read more than a fair few). Thank you.

Thank you, Jean. How nice of you to say.

Thanks for #3 – great references!

You’re welcome! There is so much to learn!

Really great insight here. Thanks for sharing your ideas Jennie.

You’re welcome, Lisa!

Excellent article. I think my writing critique group has been through many of these phases, but I’m proud of how we’re functioning now.

That’s good news! I love hearing about that kind of loyalty.

Thank you for this excellent article. I’ve been a member of a writers’ group for over a decade. We get a lot of support from one another and some good critiques. But I am aware that we are all less than candid at times. And for that reason, I’m about to join an online critique group that promises what Pixar suggests. So, now I’ll have both types of groups to draw on.

That sounds smart, Diana — as long as you still have time to do your work 😉

Hi Diana,

That is a really smart idea! would you mind sharing the name of the online critique group please? Thank you and best wishes in your writing endeavor!

Terrific article – lots of great food for thought and ways to take action, as well!

Thanks, Gayle. Glad it helps!

Great post — and thanks for the mention!

Ahh, Alexis Grant! So nice to see you here. Your a great friend to writers everywhere and I’m always happy to recommend you.