“Of all the learned professions, literature is the most poorly paid.”

—Dr. Edward Eggleston, 1890

Update / Jan. 9, 2019. The Authors Guild has released a new income survey with the usual “crisis” headline. The monumental problem with their study is this: A large number of respondents reported little or no income. Once you filter out these people, there is no longer a decline in author incomes. As Publishers Marketplace reports, “Median income for full-time published authors, once you remove the people reporting nothing at all, was $20,857. In fact, despite the focus of the study conclusions, full-time authors saw their median income rise 13 percent since 2013, and romance/romantic suspense authors also saw gains. For the 63 percent of authors who reported receiving book related income in 2017, the average total income was $43,247, which paints a very different picture [than the Authors Guild headline of $6,080]. … Three-sevenths of full-time authors with any earnings were making over $50,000.”

Reliably, every year or so, you’ll see headlines about new research that claims author incomes are on the decline. The most recent is from the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS), a British nonprofit run by writers for writers. (Download the report here).

Before I continue with this epic-length post, here’s the short version: I don’t trust these surveys’ results and I question their usefulness in improving the fortunes of writers. Too often it feels like promotion of a self-interested narrative from writers’ organizations, with the outcome boring and predictable: There is media coverage that claims writers’ incomes are plummeting, a few big-name authors come out and try to shame publishers or even society for not valuing writers properly, debate ensues, then everyone gets back to work—until a new study emerges.

This latest gnashing of teeth has motivated me to finally write a comprehensive post about why these reports are so frustrating, in the hopes more people will ask critical questions and notice their flaws. In the long run, I hope organizations will either reassess how these studies get done, or focus on more useful support of professional authors. A brief side note for industry insiders: For the purposes of this article, I’m setting aside the fact this research may be done mainly to support arguments and legislation for strengthening and protecting of authors’ copyright and thus (presumably) their earnings potential. Frankly, I don’t think weak copyright law is the problem, and I believe such efforts have little effect on the average author—and copyright terms have been increasing steadily for 200+ years.

When considering author-income research, my concerns fall into these areas.

- How reliable is the research?

- What other data points do we have?

- If the data are directionally correct, then why are incomes declining?

- Does the research tell us something meaningful or useful about how writers earn a living?

How reliable is the research?

One challenge with these surveys is they reach out to all types of writers, not just professional authors or commercial authors. Any writer can generally take part, and it’s anyone’s guess as to the consistency in who is responding to the survey call. For example, ALCS has conducted these surveys:

- In the latest one (2018), ALCS commissioned CREATe at the University of Glasgow to conduct the survey. It reached 5,523 writers which includes “everyone from full-time professionals to occasional contributors.”

- In 2014, research was conducted at the University of London and included 2,500 writers. The report says, “The majority of respondents were professional authors who spent most of their working lives writing. Overall the respondents represented a varied group, writing in different contexts and for diverse markets.”

- In 2005, research was conducted by Bournemouth University and included 25,000 British and German writers. Surveys were sent to members of ALCS and two professional bodies in Germany. Here’s that report.

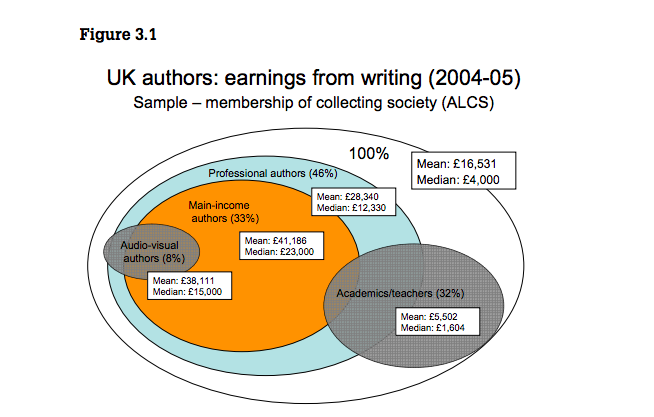

The 2005 study is probably the best and offers the most thorough detail; it separates out main-income writers (50%+ income from writing) from professional writers (50%+ time spent on writing), and also indicates the percentage of those who are academics/teachers. You won’t find this breakdown in later studies, at least in no public version I could find.

The conclusion of the 2018 study is that the median annual income of professional writers in the UK is down by 15 percent since 2013. If the group is expanded to all writers, then the decline is 33 percent since 2013. But the main-income category isn’t cited in recent research; I don’t know why.

So, what is a professional writer for the purposes of this study? Aside from being defined as someone who dedicates over half their working hours to writing, ALCS says that respondents (at least in 2014) included teachers, journalists, author-illustrators, poets, translators, scriptwriters, academics, playwrights, and comedians. (!) These obviously represent very different fields with varying levels of commercial potential. By mixing them together, it makes it difficult to draw valid conclusions about earnings trends for, let’s say, the average novelist. And let’s be honest: When these studies are reported in the media, the image most people pull up in their minds is their favorite commercial author.

I’m not trying to pick on the ALCS or its researchers’ methodology. Other such research has the same or similar flaws—usually a too-diverse pool of writers being surveyed not to mention the self-selecting nature of the survey. When the US-based Authors Guild conducted a survey in 2015, it asked its own membership to respond. That’s going to slant the results and tell you something more about the type of person who belongs to Authors Guild than the fortunes of writers more generally.

It’s also problematic to rely on authors’ guesses or memory of their income. I recently participated in an authors’ income survey, and it asked me to come up with earnings figures from the most recent year, a year before that, and five years ago. Fortunately, I have that info at my fingertips because I keep good records immediately accessible to me, but how many writers do? How many bother to check and how many just guess?

And: what if the authors surveyed are producing less than in prior years? This is another factor not taken into account—and it’s an important one. What if responding authors (often more likely to belong to an authors’ organization) have been coasting on older books that have declining rates of sale? What if they are producing work they can’t sell because their work is no longer as commercially viable as it once was? For example, only 19 percent of respondents in the 2018 ALCS report are age 44 and younger; 33 percent are 65 and older. This isn’t about ageism (or at least I hope not); it’s about writers reaching retirement and the end of their careers.

If these studies are going to be more reliable and trustworthy—while still surveying the authors themselves—they should try to:

- Revisit the same writers year after year and ask about earnings; if possible, validate the responses through documentation

- Categorize writers’ earnings based on their primary genre, category or medium

- Focus on full-time professional writers if we really want to study full-time author earnings and not, say, professors who also write

- Ask about the volume of work being produced and if it’s consistent from year to year

Some people write on the side because they have the luxury or leisure time to do so; I question why they should be included and discussed in the same studies as professional or full-time writers’ earnings, as it ends up creating misleading narratives and muddies the waters. This raises the issue, however, of how prevalent it is for writers to pursue or hold other jobs because writing doesn’t pay a living wage. I’ll comment on this in the last section below—regarding the meaningfulness or usefulness of these studies.

What other data points do we have?

Unfortunately, not many. Earlier this year, Nicola Solomon of the UK’s Society of Authors put out a call for publishers to reveal what they pay authors. The Society argues—based on UK publishing industry figures—that the percentage of publisher revenue going to authors is somewhere around 3 to 5 percent. However, Profile Books, an independent UK publisher, reported that 22 percent of its revenue goes to authors.

Update (8/17/18): It’s actually 19 percent that goes to authors; the original report got it wrong!

Why the gap? When a London literary agent, Andrew Lownie, weighed in on the issue at Publishing Perspectives, he said fewer than 15 percent of book sales made in the UK will result in the best royalty rates for writers. Discounts and special sales to large retailers and wholesalers reduce the basis on which royalties are calculated. Once again, we’re confronted with how different authors publishing different types of work can expect to earn different amounts—further undercutting the meaning of any all-in-one study.

As a side note, it may be that US authors have it better than UK authors. In June 2017, Michael Cader of PublishersMarketplace wrote an article (subscription required) guessing at what US authors earn; part of his motivation was to synthesize data from both traditional publishing and self-publishing—using Author Earnings data to help fill in the gaps. His key points:

- In the US, traditional publishing authors mostly “earn” from advances, not book sales; at large publishers, 75 percent of their advances are not earned out—but that is by design. (Successful authors receive a much higher effective royalty rate as a result.)

- Cader estimates self-publishing authors make up about 20 percent of all author earnings in the US. (Note these are authors not normally reached by the usual surveys.)

- Cader writes, “HarperCollins CEO Brian Murray has said in public they invest ‘over $200 million a year in new works.’ That suggests they pay at least 12 percent of annual revenues in advances every year. And Penguin Random House consistently carries … close to 800 million Euros for future projects under contract. … That obligation is equal to about 25 percent of the company’s annual sales.”

- Cader adds, “The biggest publishers will say informally within the community that they pay around 40 percent of their sales to authors annually between advances and royalties. That’s not a published or verifiable number, but it’s not out of step with what’s findable.”

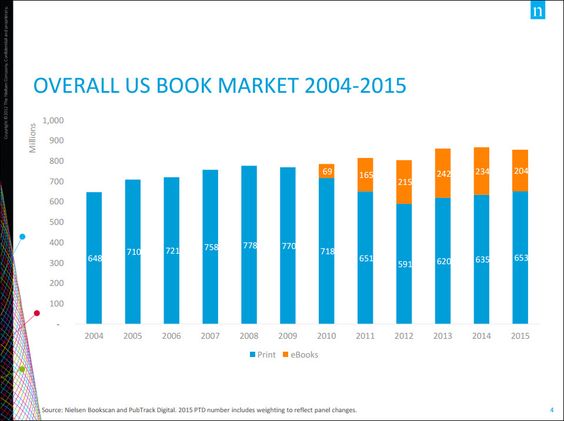

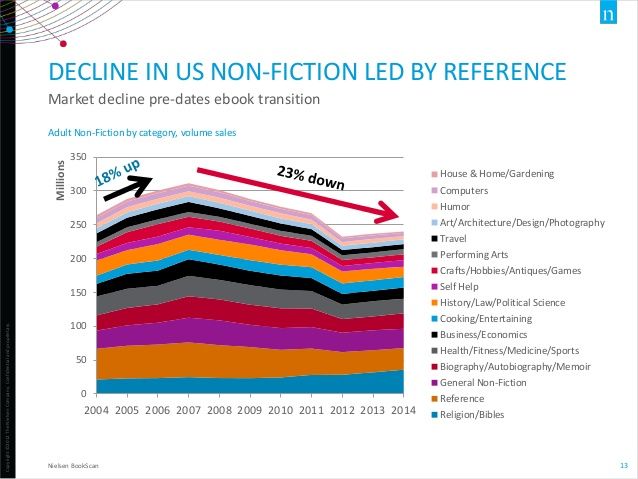

One question I’m unable to answer: whether those percentages Cader cites have been consistent over time. Traditional publisher earnings and profits have been doing quite well in the digital age—and are trackable and verifiable. The chart below from Nielsen gives us an indication of the stability in the US market over the 2000s, and the UK market is similar in its stability (if not size). So one would expect authors’ earnings from traditionally published work to be fairly consistent or modestly growing alongside publishers’ earnings. That brings us to the next question.

If the survey results are directionally correct, why might author earnings be declining?

When these reports hit the major media, the blame almost always falls squarely on book publishers. In The Guardian, the headline is “Publishers are paying writers a pittance, say bestselling authors.”

However, the survey data don’t prove that publishers are the cause of the decline. Rather, that’s the spin applied to the data—at least by The Guardian and the bestselling authors they interviewed. As you might imagine, it’s not hard to find an author willing to complain they’re not paid enough by publishers. In addition to publishers, Solomon blames Amazon for not sharing in its profits—another common refrain, especially in the US market.

Let’s assume that this survey is surfacing a real decline in earnings among the professional writer class while, at the same time, publishers’ revenues are increasing. What might be going on? A quick list off the top of my head:

- As Lownie points out, a greater share of sales may be in discount/bulk sale categories where authors are paid a lower royalty rate.

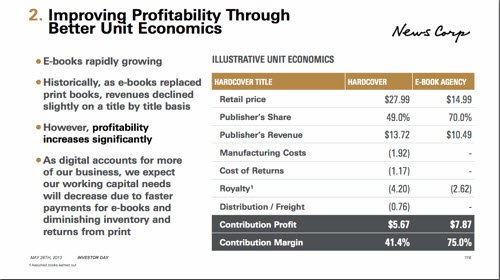

- Publishers earn a better profit margin on ebooks. See chart below, “Improving Profitability Through Better Unit Economics.” As ebook sales grow, authors would not see their earnings match publisher growth. The Authors Guild addressed this “elephant in the room” in 2015.

- Publishers may be more fiscally conservative in their advances and no longer pay that effective higher royalty rate as described by Cader.

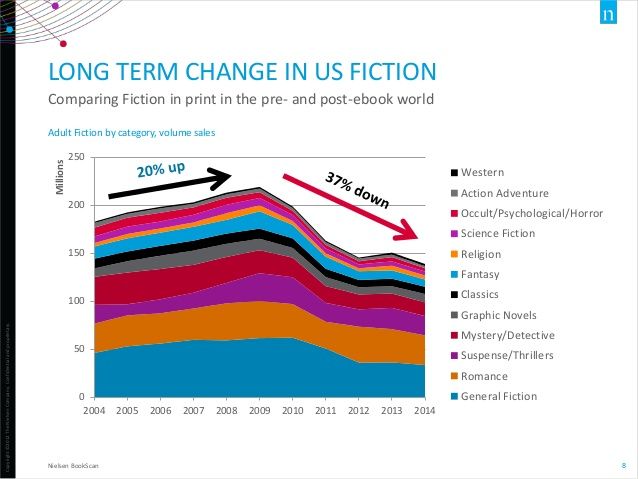

- The authors being surveyed may be writing in categories that have suffered declines in readership and sales over the years. See charts below; they are somewhat dated now, but recent industry reports show that frontlist fiction is flat to declining. YA/juvenile categories see growth whereas adult fiction does not, at least in the US.

- Even though traditional publishing revenues are up, it may be driven by increased pricing or by products that don’t require authors or royalties. For example, coloring books were a huge contributor to print growth a couple of years ago.

- Self-publishing authors may be taking away market share and earnings from traditionally published authors, especially in fiction categories.

It would, of course, be fabulous if publishers offered some transparency, as Solomon requests, on the percentage of their revenues or profits that ends up going to writers. That seems unlikely, but some independent publishers may have the freedom to be so open. Literary agencies, too, might be able to offer trends they’ve seen from year to year, without divulging sensitive figures about specific clients.

Do these studies tell us anything meaningful or useful?

The most recent ALCS study says, “Full-time writers are still very much the exception rather than the norm and we are still seeing that writers need to develop ‘portfolio’ careers in order to make ends meet. The number of authors earning their income solely from writing appears to have stabilised and is fairly consistent with the 2013 figures, but is still depressingly low at 13.7% and is still only a third of the number of full-time professional authors recorded in 2005. The research showed that, on average, income from publishing makes up the largest proportion of the professional writers’ income, but that this is supplemented by other areas such as lecturing, self-publishing and teaching…”

So why isn’t the headline of these research studies something like, “Author income from those who earn solely from writing is stable” or “Authors employ varied business models to earn a full-time living”? Even “Authors don’t make a living primarily from book sales” would be a great alternative.

Something I keep saying (and have explained, at length, in my book The Business of Being a Writer), is that the writer who makes a living from book sales alone is the exception and not the rule in traditional publishing. Were things that different in past decades? That’s the idea you might take away when reading The Guardian’s reports on ALCS research, where they inevitably quote an author saying, “You used to be able to make a full-time living from writing.” But what does that really mean?

- That you could once expect a generous advance for every book that equated to a full-time living every year?

- That you could once survive on royalty checks indefinitely?

- That you could write one book a year and live comfortably regardless of the commercial potential?

- That you could live by book sales alone without engaging in any other activities at all?

I suspect the meaning varies by author, but here’s the bottom line. These studies show significant percentage declines, but only because the base of earnings is quite small to begin with. In 2005, professional authors’ earnings solely from writing was 12,330 British pounds. In 2017: 10,437 British pounds. Given the age of writers being surveyed, the guesswork involved in estimating one’s income from years prior, and whatever changes have occurred in the market (as discussed above), this starts to look like a rounding error and not a crisis.

What most frustrates me, year after year, is why we believe or assume that authors have ever earned a reasonable full-time living from publisher advances or book sales. If these studies help make young writers (especially those paying for MFA degrees) more aware of the reality, then I’m glad of the wake-up call.

Was there some golden age—perhaps as publishers consolidated and chain retail emerged—that offered authors a more lucrative living or the potential to earn a full-time living more easily than ever before? I doubt it, but if so, that was a singular era. The history of authors’ earnings is one that’s beleaguered and fraught with anxiety. Back in 1991, during a time that some consider that “golden age,” full-time writer George Packer wrote in The New York Times, “The notion of literature as a steady livelihood now seems pretty absurd.” (He was comparing 1991 to the Grub Street era.)

If we go back to the beginnings of modern authorship, in the decades after the printing press emerged, we can learn from The Coming of the Book that “Authors who could command large sums from their publishers were very few. In fact, except for a few isolated cases, the money an author received was still meagre. To subsist it was necessary to have recourse to other means and to continue to sell prefaces and dedications.” In other words, authors needed patrons once upon a time—and still do.

The people responsible for conducting this research will argue that if publishers don’t change their ways and pay the author more, it will mean the decline of literature and overall diversity in the field. There is zero evidence this has ever happened or will happen. At the very least, since 2010, self-publishing and digital publishing have shown how much great work is overlooked by publishers every day, and only makes it to market because of authors’ own innovation, motivation, and sources of support. And thus it always has been. Most writers, regardless of how they publish, are motivated not by money, but some other reason. Prestige. Infamy. Status. Visibility. A million other things.

However, it’s not that art or literature can’t pay; it’s that most writers aren’t willing to make the compromises required to make a living from it. When the 2014 ALCS report was issued, The Guardian ran it with Will Self as the poster child of collapsing author incomes. Sometimes I feel like I’m the only person who noticed the feature of Self just a couple of years prior, also in The Guardian, where he proclaimed he doesn’t write for readers—and he considers that the characteristic of a serious writer.

All well and good, but that’s someone who needs government support for the arts if he wishes to be unconcerned with the commercial return of his work. Publishers can’t take that attitude and expect to survive; writers who intend to earn a full-time living should expect to put together an earnings model that’s diverse and multi-faceted (with patrons, grants, speaking, etc.), or become attuned to the commercial market and produce work accordingly.

I leave you with this quote from Authors & Publishers by G.H. Putnam, published in 1897, when animosity between the author and publisher populations reached a fevered pitch. (Notably, it was during this era that the figure of the literary agent emerged, as well as what we would recognize today as a standard royalty contract.)

“If there is any truth in the picture which represents the publisher as a sort of ogre, whose den is strewn with the bones of authors, and who quaffs his wine out of their skulls, this assumption is certainly natural enough, as between the eater and the eaten there can be little love lost. It must be admitted that the reminiscences of authors do contain not a few instances which serve to justify this vulgar impression as to the piratical and profit-absorbing tendencies of publishers. … The author who has experience in literature and knowledge of business is … ready to recognize that, while in certain undertakings the results may be unsatisfactory or may bring ‘inequities’ for one party or the other, the series of transactions between authors and publishers must, as an entirety, be regulated by the same inexorable laws of supply and demand, and under the same pressure of competition, which control all buying and selling. The interests of authors and publishers are, like those of all producers and distributers, practically identical.”

For even more discussion and food for thought, I highly recommend John Scalzi’s Author Incomes: Not Great, Now or Then

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

So many good observations here, Jane. As usual, you approach the topic with the depth that’s required. Well done!

Thank you, Harald!

“If the survey results are directionally correct, why might author earnings be declining?”

It might be worth looking into how many trad pub books are sold in the UK under a deep discount. I just heard from Robin Sullivan that most of her husband’s books were sold that way in the UK, costing him most of the potential royalty. If deep discount deals are common in the UK then it might explain part of the drop in author income.

I appreciate your insight on another way to view the recent survey, Jane, and what you share about data and results through the years. Your points create meaningful conversation and thought about compensation reporting in the industry.

Thanks, Shirley. Much appreciate you taking time to comment!

As a Brit I never believe what the London media write or show on TV about the writing life. This is because London literati newspapers like the Guardian are still living in the past of 3 hour alcohol fuelled literary lunches between editor and writer, trendy launch parties with illiterate B-list celebrities, talk show interviews about the deep and meaningful metaphors in some drivel written about modern society. You are right on the nose with your observations and any self respecting university would run a mile from the biassed conclusions from poorly gathered data. Who cares because we in the Indie world know what is going on and those sailing the Titanic of traditional publishing should start counting the lifeboats. 🙂

[…] Writing may be an art, but publishing is a business. To help with the business side, Anna Castle offers tips for author businesses on managing research trip costs, and Steve Laube has advice for new authors for working with their publishers, while Jane Friedman maintains that author income surveys are misleading and flawed and focus on the wrong message for writers. […]

Meaningless indeed.

Talking of how much of publishers dollars goes to authors as a group says nothing of which *authors* get that money.

How much goes to the top three/four “big name” authors, how much goes to disguised political contributions in advances for politician books, and how much goes to newcomers?

One thing Author Earnings tries to do is show the income spread for different author categories; legacy authors who established themselves in the pre-digital era, mid-listers, debut authors, etc.

Likewise, the publishing trade press seems to go out of its way to obfuscate what little data filters through by conflating textbooks, museum guidebooks, artbooks, (yes) coloring books, along with graphics novels, bios, litfic, and straight entertainment fiction. Obscuring the fact that each category, whether in print or digital, is a separate and distinct market with its own dynamics, its own trends, and its own audience. Just this week, Publishers Weekly breathlessly reported “Print sales up 2%” while later admitting that it was only due to a 4% rise in non-fiction unit sales caused by two ghost-written political books and that all other categories had declined. That kind of print uber alles cheerleading helps nobody at a time when even the giant multinationals are (still) recording 20% of their revenues from digital despite their best efforts to steer readers to print. (In the process, hurting Apple, Kobo, Google and the rest of Amazon’s competitors who only sell digital. Jeff Bezos undoubtedly blesses their little hearts.)

It matters which book market you seek to analyze if only because digital and Indie, Inc, have different sized footprints in different markets and, in the fiction markets, different footprints by genre. To the publishers a sale is a sale regardless of whether it be a cookbook, coloring book, or a prize-winning literary masterpiece. But to the author depending on their sales to pay the bills those distinctions are crucial.

The data *is* obtainable –publishers know exactly what they sold at what price, so transparency is achievable.

But you’re not going to see that data as long as they and their cronies can obfuscated, conflate, and dissemble.

Knowledge is power. Why would they give any of it up?

And what better way to obfuscate than with skewed surveys that bring to life the story of the three blind men and the elephant?

Great article. It just goes to show that you have superb critical thinking skills that are so much lacking in today’s society.

Of course, most people can disregard my comments given that I am one of those writers whose books (mainly self-published) have given him a pretax income that is better than not only that of 99 percent of writers in his country but also better than that of 97.5 percent of all the working stiffs in his country. This, by working only one or two hours a day. For the record, I once joined the Writers Guild but I found it operated out of the victim mentality and the world-owes-me-a-living syndrome just like ALCS. In short, it’s better to distance oneself from these organizations if one wants to create true success and extraordinary prosperity in one’s life.

You pointed out many of the things I’ve been saying for years – but you’ve got the credentials so people might actually listen! lol Surveys like these do nothing to inform writers (or the public) and in general get people ranting off into the sunset before they realize they’re riding a horse-less saddle.

Bingo #1: “What most frustrates me, year after year, is why we believe or assume that authors have ever earned a reasonable full-time living from publisher advances or book sales.”

Bingo #2: “However, it’s not that art or literature can’t pay; it’s that most writers aren’t willing to make the compromises required to make a living from it.”

Excellent piece.

Thank you for this. Your last quote seems to say it all.