In this installment of 5 On, author and editor Victoria Zackheim discusses (among other things):

- the art of marketing when published by a press with a limited budget

- keys to successful essay writing

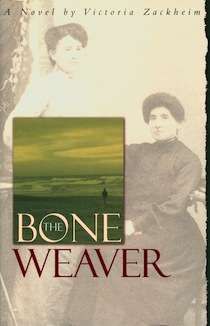

- the struggle she experienced with her novel, The Bone Weaver.

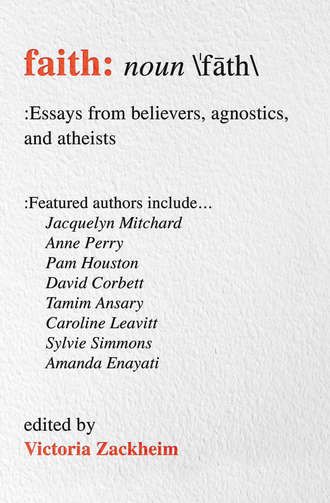

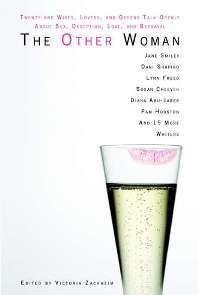

Victoria Zackheim is the author of the novel The Bone Weaver and editor of six anthologies: He Said What?: Women Write About Moments When Everything Changed; The Other Woman: Twenty-one Wives, Lovers, and Others Talk Openly About Sex, Deception, Love, and Betrayal; For Keeps: Women Tell the Truth About Their Bodies, Growing Older, and Acceptance; The Face in the Mirror: Writers Reflect on Their Dreams of Youth and the Reality of Age; Exit Laughing: How Humor Takes the Sting Out of Death; and the upcoming FAITH: Essays from Believers, Agnostics, and Atheists (Feb. 2015).

Victoria Zackheim is the author of the novel The Bone Weaver and editor of six anthologies: He Said What?: Women Write About Moments When Everything Changed; The Other Woman: Twenty-one Wives, Lovers, and Others Talk Openly About Sex, Deception, Love, and Betrayal; For Keeps: Women Tell the Truth About Their Bodies, Growing Older, and Acceptance; The Face in the Mirror: Writers Reflect on Their Dreams of Youth and the Reality of Age; Exit Laughing: How Humor Takes the Sting Out of Death; and the upcoming FAITH: Essays from Believers, Agnostics, and Atheists (Feb. 2015).

Her play, The Other Woman, based on her first anthology, will be featured in OneNight/OnePlay, and her play Entangled, an adaptation of the memoir Entangled: A Chronicle of Late Love, is in development at Z Space in San Francisco. Victoria’s first screenplay, MAIDSTONE, is now in development. She is story developer and writer of Where Birds Never Sang: The Story of Ravensbruck and Sachsenhausen Concentration Camps, aired nationwide on PBS. She teaches Personal Essay in the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program. Victoria was a 2010 San Francisco Library Laureate.

5 Questions on Writing

KRISTEN TSETSI: You’ve written a novel (The Bone Weaver), essays, a documentary, a screenplay, and you’ve adapted two books into stage plays. Which form appeals to you the most as a writer?

VICTORIA ZACKHEIM: As much as I love the personal essay, I receive the greatest joy from film and theater. Perhaps it’s because I’m so visual, and I “see” the scenes unfold. As soon as the characters are positioned in the scene, the dialogue falls into place.

With essay, I have to dig into my most personal emotions, whereas film and theater allow me to create fictional lives: back stories, experiences, emotions, dreams. And while I admit that those characters often mirror a part of me, that “distancing” allows me to explore without fear of self-exposure. (You notice I haven’t addressed the novel—that form terrifies me!)

What is the most common mistake beginning essay writers make?

The most difficult challenge is the ability to dig into our emotions. I tell my students that they can scratch the surface and get dirt under their fingernails, or they can take out the shovel and dig even deeper, or they can rent a two-ton excavator and really get at the truth.

The second challenge is to avoid shackling the reader with too much information. We don’t need to know exact dates, or the names of fifteen family members. If there are five siblings, and we need only that information, why tell us their names and ages? Even little things, like writing Boston, Massachusetts, when most readers know where Boston is.

As for the content of the essay: there’s a format that always works, but few writers hold to it. When I teach my Personal Essay course in the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program, I always run into resistance, until that light goes on in the student’s head, when I make them focus only on the opening paragraph. It’s vital, and it should be short, clear, stating the purpose of the essay. Period. All specific information comes after.

This opener has two primary purposes: (1) reveal the subject/theme of the essay, and (2) compel the reader to move on to paragraph two! Here’s an example of what doesn’t work and what does in the opening paragraph:

NO: On April 18, 1968, my parents sold our house at 1234 Tree Street in Akron, Ohio, and moved us to Topeka, Kansas. I was twelve, my brother Tom was sixteen, my twin sisters Martha and Molly were eight. None of us wanted to move, but my father’s company, BG Brown Forklifts, promoted him to Manager.

YES: When I was twelve, my father’s promotion meant we had to leave our home in Akron and move to Topeka. My three siblings shared my dread of leaving a place we loved, and trying to start a new life among strangers. While they made the adjustment quite well, I did not. In truth, I was affected so dramatically that it would be decades before I could recover from the damage and live a normal life.

What sets these two apart? The key to a good essay is conflict, and the story’s (and character’s) arc. People have to change during the story, whether fiction or non. What was learned? What was not? What was achieved/gained or not?

You said in an interview that you decided to take creative risks when you turned 60. Why did it take so long, and how did a fear of taking risks impact your earlier creative output?

I lacked the confidence to take risks when I was younger. I took them, certainly, but I inched into them, cautious and mindful of the pitfalls. At 60, I wasn’t braver, just older! And I realized that time was rushing by, and if I wanted to try new avenues, I’d better do it now.

After that declaration (to myself and to workshop and event participants), the bravery arrived in stages. With every new risk came something wonderful, including the courage to “up” the risks. Now that I’m 70, I have all the courage and confidence required, so I need only create the projects. The biggest of my life and career will happen this year, and I’m more than ready for the challenge.

Subject matter tackled in the anthologies you’ve edited, in no particular order, includes adultery (The Other Woman), things men said to women—good or bad—that changed the nature the relationship (He Said What?), women’s attitudes toward their bodies (For Keeps), the exploration into the person our families expected us to be, and the adults we became (The Face in the Mirror), and the humorous side of dealing with the death of a loved one (Exit Laughing). Coming soon: essays about faith, or lack thereof (Faith). What inspired Faith, and what’s next?

Subject matter tackled in the anthologies you’ve edited, in no particular order, includes adultery (The Other Woman), things men said to women—good or bad—that changed the nature the relationship (He Said What?), women’s attitudes toward their bodies (For Keeps), the exploration into the person our families expected us to be, and the adults we became (The Face in the Mirror), and the humorous side of dealing with the death of a loved one (Exit Laughing). Coming soon: essays about faith, or lack thereof (Faith). What inspired Faith, and what’s next?

This voyage into the exploration of faith started (as do all my anthologies) with my own soul-searching. My mother was a “mean” atheist, believing that anyone who believed was a fool. I was well into my sixties before I began to seriously explore what I believed. (Not coincidentally, this happened the year after my mother’s death.)

Why, when standing above the magnificent coast of Big Sur, did I feel emotionally overwhelmed by the beauty? What made me pull off a highway early in the morning to watch the sunrise, moved by the realization that I would never again see that sky with those colors?

During a drive from Los Angeles to my home in San Francisco, the book came to mind, along with ideas for my own essay. By the time I pulled into my garage, I knew what this book would be—gifted authors answering the question What do I believe? Whether they were atheists, believers, or agnostics wasn’t important, as long as they explored their beliefs in the essay and shared that exploration with the reader. With this in mind, I immediately called my friend, mystery writer Anne Perry, a woman whose beliefs are deep and unshakeable, and with whom I’ve shared hundreds of hours of discussion on faith. “Do it!” she said. And I did.

What’s next? I do have an idea for another anthology, but I’ll keep it to myself for the time! I’m working on two plays, both in development, and awaiting word from my director about the screenplay. The money hunt is on, which drives me crazy! And one of the plays is part of a major project, which I can discuss in a few months.

You’ve said that you usually have expectations about what you’ll receive after putting out a call for essays, but that what you ultimately get is often surprising. For example, you thought you might read a stack of man-hating rants after your call for He Said What? essays, but what you received instead were insightful and touching pieces. What did you expect after soliciting submissions for Faith, and what actually arrived?

I have a friendship or a working relationship with nearly every author who wrote an essay for this book, and so I was quite sure about their beliefs and what they would write. On more than a few, I was so wrong that it still makes me laugh. Yes, I did expect some kind of anti-religion rant from Malachy McCourt (which he delivered!), and I certainly expected a beautifully written and heart-felt essay from Anne Perry (perfection), but Caroline Leavitt’s essay about tarot card and psychics caught me by surprise. She’s a dear friend and I should have expected something unique and compelling, but this was tantamount to discovering gold.

Tamim Ansary delivered a thoughtful and thoroughly engaging essay about how an outing with his small daughter transformed him, while Sylvie Simmons wrote about her childhood love for, and fascination with, Jesus. Frank Dabba Smith, a rabbi in London, shifted gears in his essay. The first draft focused on Albert Einstein, and then he tossed it and took out that excavator, revealing to us his significant interfaith work toward peace in Israel, England, and Jordan. I could describe every essay in length—no two are in any way similar—but I’d rather your readers read the book!

5 Questions on Publishing

The Other Woman features contributions by such figures as Pulitzer Prize winner Jane Smiley and Canadian television personality Mary Jo Eustace, the former wife of Dean McDermott (who is now reality-famously married to Tori Spelling), among others. An appealing lineup for readers, but how do you select the writers for the anthologies? For Exit Laughing, for example, did you already know about a certain number of writers who had lost someone, or did you already like certain writers and, in a way, count on them having experienced the death of a loved one? And do you have to be careful with wording, particularly when the subject is as sensitive as other women?

The Other Woman features contributions by such figures as Pulitzer Prize winner Jane Smiley and Canadian television personality Mary Jo Eustace, the former wife of Dean McDermott (who is now reality-famously married to Tori Spelling), among others. An appealing lineup for readers, but how do you select the writers for the anthologies? For Exit Laughing, for example, did you already know about a certain number of writers who had lost someone, or did you already like certain writers and, in a way, count on them having experienced the death of a loved one? And do you have to be careful with wording, particularly when the subject is as sensitive as other women?

I rarely consider the authors’ backgrounds or experiences when inviting them into the project. Authors are chosen based on their writing. Is it engaging, revealing, and are they willing to dig into their collection of truths and experiences and share these with readers? For Exit Laughing, I merely put forth the idea of how we use humor to soften the blow of death. I was more cautious with The Other Woman, but only because it was my first anthology. After I invited my dream list of authors (and nearly all of them accepted), and edited the book, I approached the following anthologies with far greater confidence.

Whether the number of Amazon reviews a book has is indicative of the size of its audience is hard to say, but you can at the very least assume the book with more reviews is the book that compelled more people to write about it. Were you surprised to see that The Other Woman has the most reviews, and have you ever been tempted as a result to choose a theme you know is sensational (even if important and personal to the people writing it and reading about it) simply because it will probably sell?

I wish I could do that, choose a subject because I KNOW it will sell! Many of the top sellers are based on sexual experiences, or traumas survived. For me, my anthologies are about exploring our emotions, healing our wounds, working out those elements in our lives—physical and emotional health, relationships, fulfilling dreams—that act as obstacles. The fact that writers often approach these difficult realities with humor only adds to the joy of the project. (Case in point: Carrie Kabak and Christine O’Hagan.)

You write in your essay “No Guts, No Glory” that your first public reading of The Bone Weaver—a reading that set you up to fantasize about fame and glory—attracted 120 people. This even though your publisher didn’t have the resources to do publicity or marketing, leaving everything to you. How did you do it?

I was naive enough not to know better! The book was semi-self-published, so I had enough of a financial stake to want to recoup my expenses, and at the same time put my work out there. I started by getting myself invited to book fairs around the country. And yes, I paid all travel expenses, so I designed a plan. When I knew I’d be reading in Boca Raton, for example, I opened a map of Florida and drew a circle around Boca, and then called all the independent bookstores within a 200-mile radius. By the time I arrived for the book fair, I had a half-dozen readings organized.

That first year, I think I did around ten book fairs and perhaps twenty bookstores. I felt like a traveling salesperson, boxes of books sliding around in the trunk of my rental car. But I finally sold around 2,000 books, so I recouped a good part of my expenses. When a book fair called and offered to pay all my travel expenses, I practically wept with joy! But most important was that those bookstores became supporters, and I could go back to them several years later and pitch another event around a new book.

Building relationships is vital, and I’m deeply grateful to the indies who continue to support my work. And while there’s a big move against the chain stores, I have to add that Barnes & Noble has been a major friend of my events. They’ve been supportive, shared my excitement, and have gone that extra mile to accommodate my authors and me. With the Faith book about to be launched, I’m working closely with my publisher, Beyond Words, to organize events. At the moment, there are fifteen on my calendar, and I’m sure that this number will double over the coming weeks, especially as religious groups see the interfaith messages that run through the book.

Your book tours were paid for out-of-pocket, and you traveled quite a bit. Did the appearances end up leading to increased sales? (In other words, would you recommend that someone who is largely unknown set up signings and readings at personal cost?)

That’s a tough question, and so much depends on the financial situation of the writer. Imagine flying from Los Angeles to NY for three readings, and these readings result in the sales of 100 books. When you calculate what the writer earns from those sales, the sum doesn’t cover airport parking, much less plane, hotel, train/taxi, and meals. I strongly recommend signings within driving distance of home, even if it’s hundreds of miles. Perhaps a guest room or couch is offered, so hotels won’t be necessary.

It took you 16 years between first page and completion to finish The Bone Weaver. How long did it take you to find a publisher, and did you experience any setbacks that taught you something about the process — or about yourself?

It took you 16 years between first page and completion to finish The Bone Weaver. How long did it take you to find a publisher, and did you experience any setbacks that taught you something about the process — or about yourself?

I started the novel while living in Northern California, worked on it during my five years in Paris, and then continued after my return … sixteen years from start to finish, and then another few years to get it published.

Nothing is more humbling than to realize that editors aren’t falling over themselves to buy your book. When I saw that The Bone Weaver wasn’t going to find a publisher, I took the advice of Aviva Layton, a gifted freelance editor (who later became a dear friend) and approached Elton-Wolf, a small publisher in Seattle. They offered a contract where I paid for part of the expenses and they provided full marketing and PR support. In those days, the term “self-published” was a death knell, but I wanted that novel to be published and I swallowed my very large and irrational pride.

I have to add something here, a thank-you to literary agent Sandra Dijkstra. While I struggled through The Bone Weaver, Sandy read perhaps five revisions. She ended up not representing me (until my first anthology!), but it was her encouragement, and those pages and pages of notes and suggestions over several years, that kept me going. Had I not completed the novel and published it, I’m quite sure I never would have entered the world of anthologies, film, or theater.

And yes, there were many setbacks: loss of faith in myself, feeling like a hack, wondering if I should walk away from that dream and focus on being an editor. And the little disasters, such as flying to Florida for a luncheon designed around the novel and forgetting to bring books to the 100 women who had paid to attend. (I told the women that the books were free, but the mailing would cost them $18, and sold sixty books!) Every error or lack of confidence became a learning experience, and a reminder that I’m human, fallible, and able to make exciting things happen. After so many years at this, I’m quite fearless.

Writers dream of being published, and the chances of that happening today are far greater than when I published my novel in 2001. Does that surprise you? With the Internet now touching every part of our world, there are exciting and meaningful magazines, newspapers, blogs, all hungry to find articles, essays, stories, novels by new writers, imaginative writers willing to take the risk and put life and work and heart out there for the very hungry reading public.

Thank you, Victoria.

Read more in the 5 On interview series.

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called a novel “for right now” and “scathing social commentary.” She’s a former adjunct English professor, former reporter/columnist/feature writer for a daily newspaper, former writing instructor, and a former editor of the literary journal American Fiction (New Rivers Press). She lives in Connecticut.

Thanks for an amazing interview. This has so many nuggets of pure gold in it and I’m so glad I stopped by.

Yes, an excellent interview. Much to think about.

This was a really helpful interview. Thanks, Jane. I think it’s important to take stock of the setbacks and learn from them. You have to be willing to try a lot of different tactics today – some will work and others will flop, but you keep trying. The one non-negotiable, which she noted, are relationships (on and offline).

Victoria’s story is indeed heartening.

The “death knell” of being self-published — I’m so glad that’s a thing of the past. While I haven’t read “The Bone Weaver” (yet!), there are some indie PR and marketing books out there that I use all the time, and recommend constantly. Just because a major house hasn’t picked it up doesn’t mean a thing.

Many of my clients are self-published authors, and the ones that I see make it are the ones like Victoria — they never give up.

Thanks,

Mickie Kennedy

eReleases

http://www.ereleases.com/hello.html?a=76

[…] “The key to a good essay is conflict, and the story’s (and character’s) arc. People have to change during the story, whether fiction or non-fiction. — Victoria Zackheim, interviewed by Chris Jane in JaneFriedman.com. […]

Unfortunately, giving to the readers too much information, especially at the beginning of the essay, is my problem as well. It often seems to me that the reader won’t get some important details, which later will explain some really important moments of the story. And this fear makes me do this mistake almost every time.

[…] interview with author and editor Victoria Zackheim on writing essays, struggling with a novel, and much […]

[…] intriguing Q&A with Victoria Zackheim on, among other things, the most common mistake beginning essayists […]

[…] Victoria Zackheim […]