Today’s post is by memoirist and Brooklyn-based writing mentor Virginia Lloyd (@v11oyd).

Donna Ward is an Australian writer whose first book, She I Dare Not Name, has just been published in the US. She’s founded a literary journal, a small press, and worked as an editor. As someone who has been a traditional publisher and is now a traditionally published author, Donna brings a fresh perspective to the business of publishing.

VIRGINIA LLOYD: In She I Dare Not Name you have explored a subject that could be considered one of the last nonfiction literary taboos: the meditations of a woman growing older unattached to a partner or children. Why did you write this book?

DONNA WARD: I never thought about writing from a spinster’s perspective as taboo. For me it is a forgotten perspective, a way of life that was inadvertently cast to the margins in the nineteen-sixties when the Sexual Revolution crashed into the Feminist Second Wave. During those tectonic shifts these two paradigms came upon the word spinster, found it abhorrent, and chose the word single to describe anyone not living a traditional family life.

The intention was admirable—to rid spinsters of the stigma inherent in the word. Even though men chose single life in droves, conversations about being single became a conversation about women. The choice not to marry, or to leave a marriage, requires a woman to provide for herself and any children she might have. This compelled, quite rightly, extensive overhauls of legislation concerning marriage and divorce, finance and banking, employment and social security, to support families as they rapidly transformed into myriad forms.

Little wonder then, when, in my forties, I searched for a conversation on my single life and found little literature on it. And take note, back then, I was single, not spinster. I, too, had cast that word to the horizon.

My single life was a hard and bitter conversation to have with friends and with my therapist, since we were all woven in the belief that a woman beyond a certain age, still uncoupled and without children, must be psychologically damaged, sexually deviant, intemperate and socially defiant. My friends assumed I chose my life, despite the family catastrophes of which they spoke being the result of falling in love, or a fateful roll in the hay.

Nevertheless, when I confessed I hadn’t chosen this, my friends, therapist, even I, believed my situation the result of an unconscious flaw to which I must attend. No recognition of my heartfelt decision against having children without a partner. My fault, then. Not, as I now know, the outcome of innocent mismatches and unacceptable offers. Fate, if you like.

Life, I discovered, unfolds into spinsterhood the way it unfolds into family making. Sometimes it is chosen, more often, like coupling and having children, it is the outcome of a mix of accidents and decisions.

Back in the nineteen-nineties the literature I did find was overwhelmingly American. Although I felt a certain simpatico when reading Bachelorhood: Tales of the Metropolis, by Philip Lopate, a wet cold slunk through the gaps between our cultures. It was then I discovered that the life into which I unwittingly stumbled was, in fact, invisible.

I embarked on writing my life to make it visible, so we will never forget what it is to be a woman without a partner and children living in a word inhabited by a multiplicity of families.

Why did you choose to write creative nonfiction rather than fiction?

It was never a choice. I can’t write fiction to save my life. I did write a short story once, but it was so close to the life of a friend of mine I had to get permission when it came to be published. Of course this may change, everything does, after all. But this book was never going to be fiction.

It began as an awkward pop-sociology text. An attempt to prove spinsters exist, are socially marginalized, economically vulnerable, and misinterpreted psychologically. In the process I stumbled across a very real prejudice against spinsters exposed in research questions and methodologies. A bias toward traditional marriage, coupling and parenting was prevalent in research outcomes, psychological theory and practice. I believed I was not academic enough, for the task, and the task required academic rigor. I gave up.

I was about as far as anyone can get from the centre of civilization when the light struck me. Albany, on the southern coast of Western Australia. I was visiting a friend who took me to see Helen Morse performing the monologue of Joan Didion’s book, The Year of Magical Thinking. A thought slipped down the shaft of light—I could write it like that.

Didion inspired me to write a book that tells life as it is, not underpinned by ideology or theoretical frameworks, not through a lens which translates life and makes it palatable, but with a clear lens. She inspired me to tell the unflinching truth.

I set out to write a book that revealed me as a woman whose marital status, or lack thereof, is not the sine qua non of her sanity, though the absence of children does say something about the hurdles she must jump to be included in society. I set out to explore the web of prejudice against women living this life. I wanted to grab the reader by the collar and say: This life exists. This is what it is like. If your friend, colleague, or daughter lives this life, include her in yours. And, remember, she’s doing it on a single income in a dual income economy without the benefits of family backup or financial assistance.

What were the key structural questions you faced when wrestling with your material? What was your biggest challenge in writing the book—and how long did it take you to write it?

I always say the book took me two years and all my life to write. But, apart from having to live my life to write about it, I had to learn how to write the way Joan Didion wrote A Year of Magical Thinking.

I read everything Didion ever wrote. I wrote personal essays of my own, over and over. I went to writing classes, I had my work edited, some of these were published. And, to be honest, I forgot about writing the book and focused on the art of essay writing. I developed my own way of weaving personal stories to unpack a beautiful idea.

When my friend, Susan Wyndham, the former literary editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, encouraged me to write a book, I found I had a stack of raw material with which to craft a book that, by its very form, replicates the patchiness of living life, similar to an enormous portrait comprised of a thousand thousand tiny portraits of the same person.

So, with beginner’s naïveté, I threaded the linear story of my life through a set of essays that consider meaning and purpose, the mystery of existence, the mythology of romance, dating and love, the crush of exclusion and prejudice, the grit and ecstasy of solitude, living in the time of catastrophic weather, through the gaze of a spinster. I’m sure you see the folly of my ways. There were days and nights when my vision blurred and my brain hurt.

My biggest challenge came once I’d found my stride. The original essays were different in voice and structure. I employed an editor to help. They were much improved, but not yet perfect. We agreed that if the book should ever come into the light, the publisher’s editor would advise. And that is what happened. My editor simply said, Some essays are memoir and this is overwhelmingly a book of meditations.

I slapped my forehead with the palm of my hand. Obvious. Brilliant. Solved. I sat down, re-wrote and re-threaded the book. That part was easy.

Congratulations on being a first-time author over the age of 60. What publishing advice would you give to other aspiring authors of a certain age?

The first thing I ever wrote was the story of Dad pouring hot water into my pale blue plastic cup. I told him hot water melts plastic. He laughed. The cup, of course, caved in and contorted with the heat. I was furious and grief stricken. My love for that cup was visceral.

I was about twelve, relationships were taut. Rather than confront Dad, I wrote the story of it. I sat with the story until I fell into it and could describe every inch and second of it, got the feelings just right. Engrossed in writing I became aware of my imaginary audience. I was obligated to tell the story so they understood what happened, understood the insight I had that day—fathers can dismiss their daughters even when the father is a scientist and the science of the situation is undeniable.

When I sat back and looked at the story it was only one page long. Compact, contained. Bearable passion. But did it get the message across? I was unsure.

A few days later I walked into the kitchen. Mum was there.

I read your story. It’s silly what Dad did. I will buy you another mug, she said.

My passion took wings.

I don’t remember the replacement mug. I lost the story somewhere down the years. What remains is the writing of it.

Last year, during lockdown in Melbourne, I read Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha again. At the end of his life, Siddhartha meets the Sadhu who invites him to sit by the river. All these years I thought that scene was about letting the river carry me through life—twirling in whirlpools, surfing rapids, slipping over waterfalls, loose as a water snake. Last year I realized the message is to sit beside the river until the river flows through you.

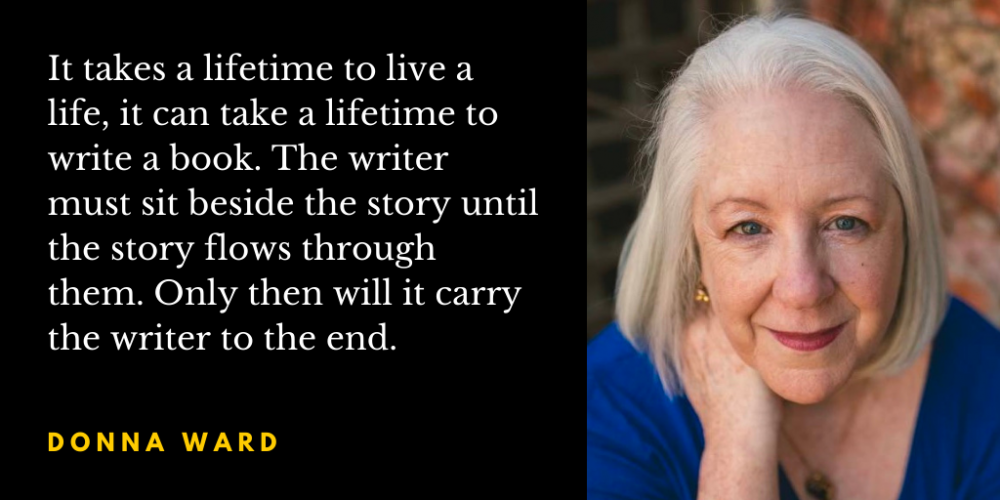

This is what it is to live, and this is what it is to write. It takes a lifetime to live a life, it can take a lifetime to write a book. The writer must sit beside the story until the story flows through them. Only then will it carry the writer to the end.

As the founder and editor of a literary magazine, and then as an independent publisher, you have made the uncommon transition from publisher to author. What did you learn from being on the other side of the publishing fence—and what could publishers learn from your experience?

Nothing focuses the mind like editing another person’s words. To climb inside their voice and rhythms, examine their grammar, even if eccentric, to ensure the writer’s meaning flows off the page into the reader’s soul, is the art of editing.

There’s a story that Michelangelo said he saw the angel in the marble and set it free. I think that’s apocryphal. Nevertheless, it perfectly captures the art of the editor. The editor sees the startling idea in the manuscript and shows the writer how to set it free.

So often I don’t know what I am writing about. I have a sense of it, and a sentence leading me into it. As I go words and phrases fall out like Hansel and Gretel’s crumbs. These hint at where I’m going. I write and write until I stop. I’m cutting the stone from the quarry. When I have the stone I begin to set the angel free. Editing taught me this.

Nothing focuses the mind like being a publisher. The publisher must feel the ears of readers awaiting these words. No matter how beautiful a manuscript, how exquisite, if a publisher can’t taste the readers’ breath, they are not the publisher for the book.

The writer must find the publisher who intimately knows the audience for their book.

When I write I listen for the reader until I can sense their sighs, their eyebrows cock, their sharp surprise. If they evaporate I stop. I wrap everything in a file and tuck it away.

I return to begin again. Being a publisher taught me this.

Originally published in Australia, your book has just been released in the US. Why does US publication remain a cherished goal for writers who live outside North America?

To be honest I never thought my book would attract an American readership. My book was released in Australia in March last year, as the pandemic spread around the world. Globally publishers pulled back, and many simply closed for business. I felt lucky to have an Australian audience.

And then there was Zoom.

To my utter surprise, Jody Day who established Gateway Women, the international network for childless and childfree women, discovered my book. She did a wonderful Zoom interview with me and bingo! I had an American readership. It’s taken a while to release it into American bookshops, and we’re releasing into the UK in November this year.

But to your question about US publication being a cherished goal for writers outside North America. Apart from the considerably larger market, and the consequent ability to earn enough from book sales to support the writing life, I believe there is something in American waters that breeds exceptional writers. I do have European and Australian writers who I admire and whose work influences me, but something in America births brilliance. Publication in America makes me feel that for a moment I stand in a room beside genius. And, if I stand quietly enough, still enough, a sliver of genius might slip into my own art—if I’m lucky.

A former literary agent and in-house book editor, Brooklyn-based Virginia Lloyd now mentors writers and subject experts seeking an agent. She is the author of two traditionally published books: The Young Widow’s Book of Home Improvement and Girls at the Piano. She has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Sydney in her native Australia. Learn more at her website.

I was utterly taken by this interview. This woman has a way of phrasing things that shows off her brilliance. I’m sure her memoir is terrific just by the way she speaks. I’ll seek it out.

As someone without a partner or children, I think it took incredible courage to write this book. I’m eager to read it. My friends and family also think I chose this life — my family thinks that I’m selfish and antisocial — nothing could be further from the truth.

Thank you. In the guest blog you did not mention how it felt to be alone without choosing to be; of course that is not the subject of your guest blog: the book is. I presume “anguish” applies regarding what it was and is like to live alone without choosing to do so, considering how people are hard-wired to be mated.

Loneliness is the default, no less than ignorance. Despondency is the place-holder inserted in one’s life, filling the gap where companionship belongs. Few people choose to live in the agony of having no one to hold, nor to be held by. It is _not_ society that suggests being alone all one’s life is pathological: it is the burning in one’s lungs when contemplating what might have been that makes one believe one is “broken.”

I have told Amazon. com to send a copy of your book SHE I DARE NOT NAME to me. Perhaps your insights and wisdom will help me learn others’ experiences of what it means to be alone and not wish to be.

Because the multiverse revolves around me:

I have lived 61 years, all of them alone— and not by choice. The 18,000+ mornings I awoke alone brought grief, as I knew I would pass yet another day wandering the world without purpose— a man needs a woman to “do for,” otherwise he is irrelevant; obsolete at birth. For the insipid clowns who insist “One does not need a mate in one’s life,” I ask them to trade places with me for sixty years and then ask themselves if they can say such an inane and vapid thing.

The thousands of nights I laid down to sleep, afraid of the night because the pain of having no one to hold, and no one to hold me, was liquid agony beating in my veins, making it a struggle to draw a breath— and wishing it was my last. None of this was a choice: I spent my past days looking for interest of me in the eyes of the women around me, and seeing only disinterest. As you wrote about your own experience, I assume it was pathology that kept me alone: I was doing something, or being something, that made all women find me unworthy of sharing her time with me.

One of my roommates, when I was around 38 years old, told me that I would “later regret not looking for a mate.” Her assumption that I was not trying was like a class shard had been slowly inserted in my chest, to rest in my heart. Somehow she believed that I was alone by choice. Perhaps she believed this because I seldom showed my feeling, let alone shared them verbally; I faced the torment of loneliness stoically, with a placid face, never showing how much I was bleeding drops of pain.

It was when I was fifty-eight years old that I learned I am autistic: I was born robbed of the ability to learn the skills of romance and love. I was and I am blind to a woman’s gaze: I was dead at birth and I did not know it, obsolete and invisible with no hope I would ever find a companion— I was (and I am) certain that something about me was too horrible for women to accept.

These days I spend toiling in the sun, alone and isolated, on a remote canyon’s floor within the canyon lands of Northern New Mexico, wondering why I bother. I dread laying down, knowing that every atom of me goes inflamed by loneliness, and there is no way to put out the fire.

To ease some of the grief loneliness has brought to me, I wrote the worlds most comic memoir. Sharing laughter is one way I cope

DMR